Previous Post in Series: A Young Virtuoso

__________

Summer Work in a Summer Playground

Baden bei Wien, painting by C. L. Hofmeister

Scheiner’s Kaffeehaus is the building with the portico on the left.

The school year over, Joseph spent the month of August and the first weeks of September with his Figdor relatives in Baden bei Wien, a spa resort frequented by affluent Viennese, including the highest nobility. [1] With its elegant public and private buildings, its warm mineral baths dating to Roman times, its wine gardens and coffee houses, its chestnut, linden and acacia allées, its flower gardens and parks, its evening illuminations, plays, concerts, balls and public readings — the town of Baden provided an idyllic escape from the heat and bustle of the city, and a pleasant opportunity for recreation and socializing. Upon the death of Emperor Franz in 1835, many of the aristocracy had ceased to summer in Baden; nevertheless, the resort was now enjoying a welcome revival since the opening of the railroad connection to Vienna in June 1841.

The American locomotive “Philadelphia,” named after its city of manufacture, was the first locomotive on the Vienna-Baden line. The first Austrian railway line, between Vienna-Floridsdorf and Deutsch Wagram, had opened only four years earlier, in 1837.

Baden had been ravaged by fire three decades earlier, on July 26, 1812, and was subsequently rebuilt, in the Biedermeier style, through a combination of public and private largesse, including the proceeds of numerous benefit concerts and readings. [2] The residents of Baden may therefore have been particularly sympathetic when they learned that the Galician (Polish) town of Rzeszów had been consumed that June in a great conflagration. A gala benefit concert and reading was organized for Rzeszóws victims, to take place on August 7, 1842, in the ballroom of the Schloss Gutenbrunn. Tickets went on sale at Scheiner’s Kaffeehaus, a sojourner’s destination since 1803, whose pleasant portico was a popular gathering place for the well-to-do; tickets were also available at one of the stately and elegant houses on Baden’s Antonsgasse, adjacent to the palace of the recently deceased Archduke Anton. [3]

The charitable musikalisch-declamatorische Akademie was probably produced by its featured performer, Moritz Gottlieb Saphir, who, in the days before regular concert series, made a specialty of organizing such events. “Saphir’s academies are living samples of the notable artists that are harbored at a given time in our residence,” gushed the Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung half a decade later; “[…] they are the fragrant flower bouquets that are chosen and picked in the art-garden of our musical delights. Saphir’s academies unite the quiet art lover with the loud art-enthusiast, the lover of wit and humor with the lover of sentimental declamation; but also the benefactor and friend of the poor and the suffering. In short, Saphir’s academies are the unifying point of the most heterogeneous tastes; in them meets the most peculiar mix of a pleasure-seeking public. Saphir understands as no other how to cater to every palate; he is ready to provide everyone’s favorite dish.”[iii] This particular Olla Podrida of a program included an etude for piano by Thalberg, played by Dlle. Amalie Schönbrunner; a duet from Rossini’s Semiramis, performed by Dlle. Schwarz and Herrn Arcadius Klein; an unspecified poetic declamation; Ernst’s Othello Fantasy, performed by “the little violin player” Joseph Joachim; a cavatina from Donizetti’s Belisario, sung by Mad. Sophie Schoberlechner, née Dall’Occa; a duo concertante for piano and horn, performed by Herren Carl and Richard Lewy; and a humorous reading, composed and performed by Saphir himself. [4]

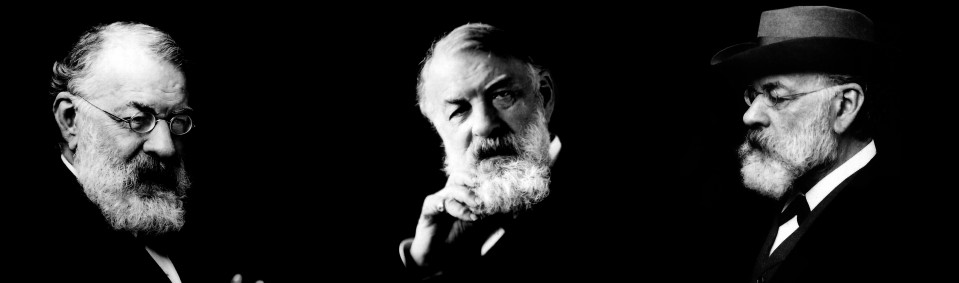

Moritz Gottlieb Saphir

Lithograph by Kriehuber, Vienna, 1835

Contemporary journals may well have raved about Saphir’s academies, but for critic Eduard Hanslick, writing in 1870, Saphir epitomized everything that was objectionable about Vienna’s pre-March concert life:

Through his consummately characterless yet dazzling wit, Saphir had raised himself to be the dominant force in Viennese journalism, and the idol of the Viennese public. They lived and breathed Saphir’s jokes. Saphir was flattered and feared as no other. The self-assurance of his wit, his jokes and word-plays, also dominated his criticism and corrupted that of the other Viennese. Saphir understood nothing at all about music; nonetheless, he wrote happily and often about it whenever he could raise one of his favorite virtuosi to the heavens, or could tread one that he disliked into the dirt. No matter how unjust he was in any particular case, the phalanx of laughers was on his side, and a witty remark could make or break a concert-giver’s fortune. The “Humorist” (a poorly edited, and, aside from Saphir’s own articles a completely trivial paper), exercised its corrupting influence on Viennese society for fully 21 years. Saphir placed himself in direct rapport with the public through the large “Academies” of which he gave two or three annually (from approximately 1834 to 1847). These academies, originally produced in the Josefstadt Theater, then a few times in the Wiedner Theater and finally in the Court Opera Theater, were a chrestomathy of all the artistry that Vienna had to offer. The most famous virtuosi and singers, the most celebrated artists of the Burgtheater and Court Opera participated in Saphir’s academies, for who among them would be so foolish as to court Saphir’s fury, or miss out on the prospect of a witty accolade, with a refusal? Saphir’s academies were the best attended and most beloved that there were in Vienna; people crowded for hours beforehand to get the best seats. And as the public wallowed in Saphir’s ironic-sentimental poems and insatiable wordplays, so journalists vied with one another in truly Byzantine idolatry over these academies. [v]

Saphir’s academies were variety shows, constructed according to a simple formula: a mixture of song, humor, dramatic reading, and virtuoso performance. In their own way, they were innovative and valuable: they helped establish a taste — and a market — for the German Lied as a genre, and Schubert’s Lieder in particular, and they provided a springboard for the talents of some of Austria’s most promising young musicians. In addition to Joseph Joachim, Saphir gave early opportunities to another Böhm prodigy, Alois Minkus, who played the Othello Fantasy at a Saphir academy in Pressburg, May 1, 1842 (earning praise, like all of Böhm’s students, for his excellent staccato); and also to the 8-year-old Moravian violinist Wilhelmine Neruda, who performed de Beriot’s sixième Air Varié in January 1847. Minkus subsequently achieved considerable renown as a composer of ballet music in Russia; Neruda, later Wilma Norman-Neruda (Lady Hallé), became one of the great violinists of the century.

“What should I say about the little eleven-year-old violin virtuoso Josef Joachim?” asked the reviewer for the Sonntags-Blätter on this occasion. “That all the audacious expectations that his admirable playing arouses in expert listeners should be fulfilled, and that he should become one of the most illustrious stars in the firmament of virtuosi! He performed Ernst’s Othello Fantasy, and anyone who knows and appreciates the unusual and multi-faceted difficulties of this work understands what it means to say that everything in it was well-done, and much was consummately played. His excellent teacher, Herr Prof. Böhm, was accorded the well-deserved recognition of receiving a bow with his brilliant little pupil.” [vi]

The Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung spoke, not of virtuosity, but of artistry:

The eminent talent of this eleven-year-old artist—(one can call him this without exaggeration)—is so universally accepted, that I limit myself to saying that no one, hearing this supremely gifted boy for the first time with eyes shut, could suspect that it was not a man playing, and indeed one who already climbed to a high rung on the ladder of maturity; for his playing unites purity of intonation, security of technique, sweep of imagination, and intimacy of expression. Here, one may expect great things of the future, and the more so, since this rare innate talent is being nurtured with all the aid and solid direction of the proven master, Herr Prof. Böhm. [vii]

© Robert W. Eshbach, 2013.

Next Post in Series: Vienna Philharmonic Debut

[1] Jews had first obtained permission to stay year-round in Baden in 1805, and in 1822, the first Jew, Heinrich Herz, had obtained a formal right of settlement. In 1839, Herz’s son Leopold occupied a house in the Wassergasse, where he opened a kosher restaurant and a Synagogue for 285 people. In 1849, Leopold Herz became the first Jew to be allowed to own property in Baden, a right that would not become general until 1860. Many of Baden’s Jewish residents came from the communities of Mattersdorf or Lackenbach in the Sheva Kehillot.

[2] Among the benefit concerts was one given in Karlsbad on August 6, by the Italian violinist Giovanni Battista Polledro, and the German pianist Ludwig van Beethoven, that raised 1,000 florins W. W. The charitable activities related to the Baden fire led directly to the founding of Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and its conservatory.

[3] Rzeszów had a large Jewish population, and the preponderance of Jewish performers at this benefit, as well as the ticket sales at Scheiner’s Kaffeehaus (Scheiner was a common Galician Jewish name), suggests that the concert may have found its principal support among Jewish social circles.

[4] Many of Saphir’s academies featured the same participants. For example, Klein, the Lewys and Saphir had also participated in a benefit for the victims of the Pest flood four years earlier, April 1, 1838, in Vienna’s k. k. Redoutensaal. [Gibbs/LISZT, p. 182]

[i] Photo credit: Kinsky Art Auctions, Vienna.

[ii] Wikimedia Commons. http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/WRB_–_Philadelphia

[iii] Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, Vol 6, Nos. 14 & 15 (February 2 and 4, 1847), p. 60.

[iv] Wikimedia Commons.

[v] Hanslick/CONCERTWESEN I, p. 365.

[vi] Sonntags-Blätter für heimathliche Interessen, Vol. 1, No. 33 (August 14, 1842), p. 589

http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?apm=0&aid=stb&datum=18420814&zoom=6

[vii] Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 2, No. 96 (August 11, 1842), p. 392. http://books.google.com/books?id=hOMqAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=editions:LCCN10024356#PRA1-PA392,M1