Joseph Joachim, an early daguerreotype

Joachim initially took up residence with his grandfather Isaac Figdor in Leopoldstadt, the district along the Danube canal that was home to most of Vienna’s Jewish population. Figdor, a widower of eight years, was a man of considerable wealth, a leader in the Viennese business community, a tolerated Jew of long-standing, and, in 1847, one of only 193 Jewish family heads enrolled in Vienna. He is said to have been traditionally strict about manners and habits, but he was also kindhearted, and gently solicitous of his grandson’s feelings of homesickness during a difficult period that left him vulnerable to what he later described as deeply rooted feelings of melancholy, desolation, abandonment and apathy.

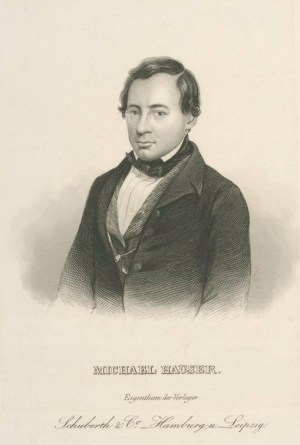

Miska Hauser

Joachim’s first teacher in Vienna was a seventeen-year-old student of Joseph Mayseder (*1789 — †1863), the mercurial Miska (Michael) Hauser (*1822 — †1887), then making a name for himself as an elegant salon player. The Joachims may have been aware of him through a local connection: Hauser came from a prominent Jewish family in Pressburg (Hauser’s father, Ignaz, was an accomplished amateur violinist, said to have been acquainted with Beethoven). It quickly became apparent that Joseph needed a more experienced teacher, however, and after only a few weeks the lessons were discontinued.

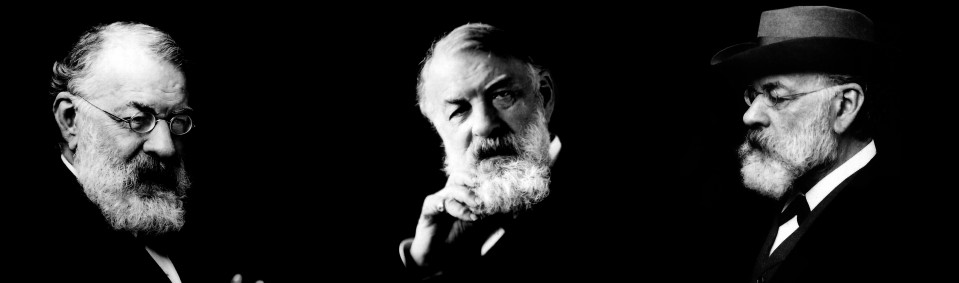

Georg Hellmesberger Sr

Portrait by Charles-Louis Bazin

Joachim was entrusted next to Georg Hellmesberger senior (*1800 — †1873), a distinguished and experienced pedagogue who had been an early pupil of Joseph Böhm (*1795 — †1876). Among Joachim’s fellow students were Hellmesberger’s two sons, Joseph (*1829 — †1893) and Georg junior (*1830 — †1852), both of whom would go on to significant professional careers. Together with Joachim and a boy named Adolf Simon, they formed a “quartet of prodigies” that on 25 March 1839 played Ludwig Maurer’s popular Sinfonia Concertante for the benefit of the Bürgerspital fund, a favored Viennese charity. “In spite of the great success of this concert, Hellmesberger was not wholly satisfied,” writes Andreas Moser on Joachim’s own authority, “for he found (Joseph’s bowing) so hopelessly stiff, that he believed nothing could ever be made of him.” Berlin critic Otto Gumprecht relates a similar story: “after nine months of instruction, [Hellmesberger declared] that he could not vouch for the student’s future, because his right hand was much too weak to draw the bow with power and endurance.” Joachim’s parents, in Vienna for the concert, resolved to take him back to Pest and train him for a different profession.

Coincidentally, Joseph Böhm’s most celebrated pupil, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (*1814 — †1865), had just arrived in Vienna, and was giving a series of highly-publicized concerts. When the Joachims turned to Ernst for advice about their son’s professional prospects, Ernst recommended Joseph Böhm as the best person to develop his talent.

Joseph Böhm

An important teacher, [Leopold] Joseph Böhm is known today as the father of the Viennese school of violin playing. His pupils included some of the leading artists of the age: Ernst, Joachim, Georg Hellmesberger senior, Adolf Pollitzer, Eduard Rappoldi, Ede Reményi (Eduard Hoffmann), Ludwig Straus, Edmund Singer, Jakob Dont and Jakob Grün. As a member of the Imperial Hofopernorchester from 1821 to 1868, Böhm played in many historically significant concerts, including a performance of Beethoven’s 9th symphony under the composer’s direction. He became an early advocate for Schubert’s chamber music, and, on 26 March 1828, he gave the premiere of Schubert’s opus 100 trio. Together with Holz, Weiss and Linke of the original Schuppanzigh Quartet, he performed Beethoven’s string quartets under the composer’s supervision. For Joachim, this direct personal and musical connection to Beethoven held a great and abiding significance.

Joachim’s training under Böhm was a true apprenticeship. In accepting him as a student, Böhm and his wife agreed to take him into their home just outside of Vienna’s first district, two blocks from the Schwarzspanierhaus where Beethoven had lived and died. For the next three years, for all but the Summer months, they would raise him in loco parentis, and train him in the practical skills of a professional violinist. Though not a violinist, Frau Böhm played a critical role in the Joseph’s musical upbringing, attending his lessons, and taking personal charge of his practicing.

Böhm had been a sometime pupil of Pierre Rode, and his method was a combination of the German and French schools. Under Böhm, the caprices of Rode, together with selected works of Mayseder, formed an important part of Joachim’s technical and musical training. In later life, Joachim could play from memory pieces by Viotti, Rode or Mayseder that he had studied with Böhm, though he had not practiced them since. As a teacher, Böhm was able to help Joseph remedy the defects in his bowing that Hellmesberger had found so ruinous.

Joachim gave his first public performance as Böhm’s protégé on 15 November 1841, playing an Adagio and Rondo by Charles de Beriot. The occasion was a gala benefit for the homeopathic hospital of the Merciful Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul, held in the in the k. k. Hoftheater nächst dem Kärntnerthore — the theater where, seventeen years earlier, Beethoven had conducted the premiere of his 9th Symphony. The long musikalisch-declamatorische Akademie featured the city’s most illustrious performers. Two months later (27 January 1842), he gave his first performance of a piece that would become his Cheval de Bataille: Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst’s Fantasie Brillante sur la Marche et la Romance d’Otello de Rossini, Op. 11 (dedicated to Joseph Böhm), first published two years earlier in Mainz.

Though he no longer concertized publicly, Böhm was an enthusiastic quartet player at home. He would occasionally allow Joachim to participate in these informal performances with colleagues, which formed an important part of Joachim’s musical education. “For Joachim,” writes Andreas Moser, “these gatherings in the Böhm household were an inexhaustible source of recollection about an epoch in the performing arts that has found its conclusion with his passing; and for me an object of inestimable edification when we later worked together on our shared edition of the Beethoven string quartets.”

Joachim studied privately with Böhm for more than two years before enrolling at the Vienna Conservatory. His name appears as a registered student there for a short time only — during the school year 1842-1843 — and then, only as a member of Böhm’s advanced violin class. At the same time, he received private instruction in Harmony and Counterpoint from Gottfried Preyer (*1807 — †1901), a faculty member at the Conservatory who was himself a former pupil of the renowned Imperial and Royal Court Organist Simon Sechter (*1788 — †1867). Joachim participated as a section leader in the conservatory orchestra, which Preyer conducted. Published conservatory records show the 1842-1843 school year as his first year, with an obligation for one more — an obligation never fulfilled. At the end of his student year, Joachim received an award of the second highest degree, the “premium with entitlement to a medal” — an award generally given to encourage and reward diligence. He received top grades for diligence, progress and morals.

Painting by C. L Hofmeister [Kinsky Art Auctions, Vienna]

At the end of the 1843 school year, Joachim spent the month of August and the first weeks of September with his Figdor relatives in Baden bei Wien, a spa resort frequented by affluent Viennese, including the highest nobility. There, he participated in a gala benefit concert for the victims of a massive conflagration in the Galician town of Rzeszów, produced by its featured performer, Moritz Gottlieb Saphir (*1795 — †1858). In the days before regular concert series, Saphir made a specialty of organizing such events. Saphir’s “academies” were variety shows, constructed according to a simple formula: a mixture of song, humor, dramatic reading, and virtuoso performance. In addition to featuring the most celebrated Viennese artists, they provided a springboard for the talents of some of Austria’s most promising young musicians. Beside Joachim, Saphir gave early opportunities to another Böhm prodigy, Alois Minkus, who played the Othello Fantasy on 1 May 1842 at a Saphir academy in Pressburg, and also to the 8-year-old Moravian violinist Wilhelmine Neruda (later Norman-Neruda, Lady Hallé), who performed de Beriot’s sixième Air Varié in January 1847. Saphir, well known as the editor of the popular journal Der Humorist, took a particular interest in Joachim, becoming his first significant promoter.

Joachim gave a number of well-publicized performances during his final time in Vienna. On 20 February 1843, he played to great acclaim at the annual “private entertainment” of Franz Glöggl (*1796 — †1872), a publisher, music shop owner, professor of trombone and bass at the Conservatory, and the archivist of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. In April, he played a Rode concerto (the program does not reveal which) in a Conservatory pupils’ concert, under the direction of Ferdinand Füchs, who had temporarily taken over leadership of the orchestra from Preyer.

That year, Joachim’s cousin Fanny Figdor, who had been so influential in helping the Joachims to send their son to Vienna, would once again play a decisive role in directing his career. In 1839, Fanny had married Hermann Christian Wittgenstein, a wool merchant some eleven years her elder, and a business acquaintance of her brother Gustav. Operating out of offices in Vienna and Leipzig — where nearly all the wool-export companies were headquartered — Wittgenstein acquired wool from Poland and Hungary and sold it in England and Holland. After their wedding, Hermann and Fanny left Vienna and settled in Leipzig, where, as it happened, Felix Mendelssohn was just then working to create a Conservatory of Music. “From her new home,” writes Otto Gumprecht, Fanny “could not report enough of the lively artistic life that surrounded her on all sides. These alluring descriptions made the deepest impression on her cousin’s mind. He resolved to complete his studies at the newly-founded Leipzig Conservatory, and despite the objections of his Viennese relatives, who, jealous of the family pride, did not want to allow him to move so far away, he persisted in his decision.” Here, as elsewhere in the literature, Joachim is depicted as having had a strong and even stubborn sense of his own best interest and future direction. Andreas Moser nevertheless credits Fanny Wittgenstein, who “exerted her whole influence to have the boy sent to Leipzig for further development in his art.” In any case, Julius Joachim was persuaded, and resolved to follow both Fanny’s advice and his son’s desire. In convincing Julius Joachim to send his son to Leipzig, Fanny prevailed over the united objections of her own father and her uncle Nathan, who often vied with one another as Joseph’s principal caregiver. More importantly, she prevailed over the opposition of Joseph Böhm, who, according to Moser, showed not a little displeasure at the idea. Böhm had wanted Joseph to follow the virtuoso route to Paris.

Before departing for Leipzig, Joachim made an important début, in the fourth-ever subscription concert of the nascent Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Playing on Sunday, 30 April, before a capacity audience at the Imperial and Royal Redoutensaal, he performed the Adagio religioso and Finale marziale movements of Vieuxtemps’s fourth concerto in D minor. Joachim had had an opportunity to hear the concerto from Vieuxtemps himself that Spring, when the young Belgian violinist had played in the same hall.

Leipzig

During the summer of 1843, Joachim travelled to Leipzig, to audition for Mendelssohn. There, he also became acquainted with his prospective teachers: Gewandhaus concertmaster Ferdinand David (*1810 — †1873), and the eminent theorist and cantor of St. Thomas’s Church, Moritz Hauptmann (*1792 — †1868). Returning to Vienna for a final visit, he gave a farewell recital. Saphir reported (20 July) in Der Humorist: “While visiting his family, the amiable violinist, Joseph Joachim, also highly esteemed in the [Imperial] Residence, has given a private academy in the salon of his uncle, the wholesaler Herr Vigdor. All that our city has to show for artists and patrons of art graced this private concert with their presence. The winsome little singer (that is Joachim on his instrument) was smothered in caresses. He who has not seen this Wunderkind with his own eyes as he performs the compositions of Classical masters would believe himself to be hearing a Nestor, or one of the modern, celebrated heroes of the violin. Joseph Joachim lacks only world renown — the aura of widespread reputation, in order to shine amongst the violin-stars of the present, both spiritually and technically. Whether his honorable family will see their wish fulfilled, to have the great public delight in their darling’s songs, is not yet determined.”

Joachim took his final leave from Vienna on August 1, 1843, traveling by post coach via Prague to Dresden, and taking the train from there to Leipzig.

© Robert W. Eshbach 2014