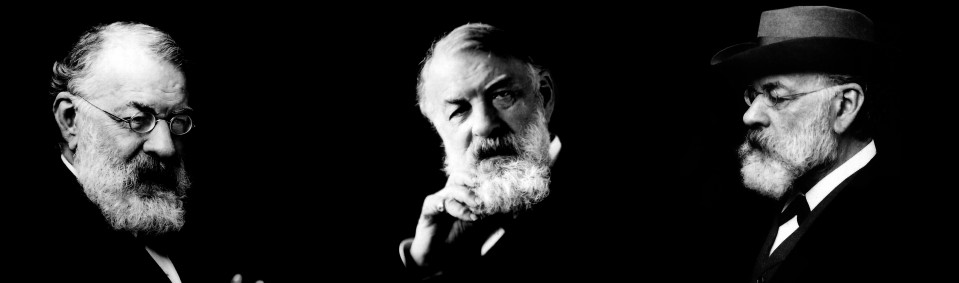

Carl Reinecke, Joseph Joachim and the Reinecke Violin Concerto, op. 141

Robert W. Eshbach

arl Reinecke’s violin concerto in G minor, op. 141 is the Sleeping Beauty among nineteenth-century violin concerti. Written for Joseph Joachim, who performed it only once, in a Leipzig Gewandhaus concert under Reinecke’s direction on 21 December 1876, it slept thereafter undisturbed until violinist Ingolf Turban recorded it with the Berner Symphonie-Orchester in September of 2004. [1] Reinecke’s concerto is a work of considerable inherent quality that never entered the repertory, and therefore had no impact on the future history of the genre. It nevertheless occupies a noteworthy niche in the evolutionary history of the Romantic violin concerto.

arl Reinecke’s violin concerto in G minor, op. 141 is the Sleeping Beauty among nineteenth-century violin concerti. Written for Joseph Joachim, who performed it only once, in a Leipzig Gewandhaus concert under Reinecke’s direction on 21 December 1876, it slept thereafter undisturbed until violinist Ingolf Turban recorded it with the Berner Symphonie-Orchester in September of 2004. [1] Reinecke’s concerto is a work of considerable inherent quality that never entered the repertory, and therefore had no impact on the future history of the genre. It nevertheless occupies a noteworthy niche in the evolutionary history of the Romantic violin concerto.

Reinecke composed two violin concerti. The first was conceived in Barmen in the year 1857, and was premiered under Reinecke’s baton by Franz Seiss. It was repeated in altered form by Ferdinand David in Leipzig, on 3 October 1858, and thereafter put aside. [2] It was never published. Reinecke himself described the work as his “totgeborenes Kind” (“stillborn child”). He had originally wanted Joachim to give its Leipzig performance, but Joachim, who had also recently received the revisions of Brahms’s D minor piano concerto, found Reinecke’s work uninspired by comparison. On 3 January 1858 he wrote to Clara Schumann: “Reinecke hat ein Violin-Concert geschickt — so gewöhnlich, so manchmal sogar ungeschickt klingend, wie ich’s von einem so routinirten Componisten nie erwartet hätte.” [3] Joachim, who never played a work that he did not believe in, refused Reinecke’s invitation.

With the Violin Concerto op. 141, the matter stood otherwise. Reinecke’s G minor concerto, which carries the dedication “Seinem Freunde Joseph Joachim,” belongs to a distinguished tradition of “Freundschaftskonzerte” that includes, among others the concerti of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Brahms. Like the other concerti in this tradition, Reinecke’s work seems to embody many of the characteristics of its dedicatee’s violin playing, as well as his general attitude toward art. A critic for Signale für die musikalische Welt mentions that Joachim took up the work “mit ersichtlicher Liebe und Hingebung.” [4] Nevertheless, Joachim’s performance at the premiere fell below his usual standard. The reviewer for the Musikalisches Wochenblatt wrote: “Die diesmalige Ausführung des Werkes war eine nur mittelmässige; weder der Solist, noch das begleitende Orchester wussten ihren Vortrag von mancherlei Unsauberkeiten, als da sind: theilweise ziemlich unreine Intonation, schlaffe Rhythmik etc., hinreichend frei zu halten. Den befriedigendsten Eindruck hinterliess als Composition, wie auch hinsichtlich der praktischen Ausführung, der zweite (langsame) Satz des Concertes.” [5]

Reinecke’s concerto never won a place in Joachim’s concert repertoire; it is likely that it was crowded out by the appearance, the following year, of Brahms’s Violin Concerto in D major, op. 77. Though it was published by Breitkopf und Härtel in October 1877, no other violinist seems to have taken it up, perhaps out of deference to its prominent dedicatee. When Joachim and Reinecke next performed together, Joachim played Spohr’s E minor concerto (likely no. 7, op. 38, a favorite of Joachim’s), and the second movement of Joachim’s own Hungarian Concerto, op. 11. [6]

*

* *

Program: Stadtgeschichtliches Museum Leipzig

Carl Reinecke and Joseph Joachim met for the first time in 1843. Reinecke was nineteen years old, and Joachim twelve, when they made their Leipzig debuts on the same 16 November Gewandhaus program. In his memoir, Erlebnisse und Bekenntnisse, Reinecke recalled the event:

“[…] da trat ein zwölfjähriger Knabe im Jäckchen und mit umgeschlagenem Hemdkragen auf und trug die seinerzeit berühmte Othellophantasie von Ernst mit vollendeter Virtuosität und mit knabenhafter Unbefangenheit vor. Es war Joseph Joachim, dem am Schlusse das sonst etwas reservierte Gewandhauspublikum stürmisch zujubelte. […] Daß das Publikum meine Leistung zwar freundlich aufnahm, mir aber nicht in gleicher Weise zujauchzte wie dem zwölfjährigen Wunderknaben, kränkte mich nicht, denn ich war verständig genug, um es für selbstverständlich zu halten, daß das Publikum einen Knaben, der auf seiner Geige das ganze Feuerwerk eines brillanten Virtuosenstückes hatte aufblitzen lassen, enthusiastischer belohnte als einen neunzehnjährigen befrackten Jüngling, der die liebenswürdige, aber keineswegs bravourmäßig ausgestattete Serenade von Mendelssohn vorgetragen hatte.” [7]

In the immediately ensuing years, Reinecke and Joachim had ample opportunity to form a close musical and personal relationship. Reinecke remained in Leipzig until 1846, returning briefly in 1848. Joachim lived in Leipzig until October 1850, after which he settled in Weimar as concertmaster under Franz Liszt. During their Leipzig years, the two young musicians performed together frequently, in both private and public settings, often in partnership with Gewandhaus colleagues Ferdinand David, Moritz Klengel, Niels Gade, Andreas Grabau, and Franz Carl Wittmann.

Though primarily a pianist, Reinecke was also an accomplished violinist. “Meine Violinstudien,“ he wrote, “mußte ich zunächst nach der Schule von Rode, Kreutzer und Baillot, später nach der von Spohr betreiben. Ich brachte es schließlich bis zu dem ersten Konzert von de Bériot und dem jetzt vergessenen in Es-Dur von Spohr. Mein größter Stolz als Geiger bleibt aber, daß ich einst der Witwe Felix Mendelssohns im Verein mit David, Joachim und Rietz einige Quartette von ihrem dahingeschiedenen Gatten vorgespielt hatte.“ [8]

Active composers both, Reinecke and Joachim belonged to the circle of Mendelssohn and Schumann. They shared many musical opinions, among them a strong antipathy toward virtuosity for its own sake. [9] This bias is evident in Reinecke’s late assessment of Joachim’s musical career:

“Ganz naturgemäß stak Joachim bei seinem Erscheinen in Leipzig noch ganz im Banne der Virtuosität, aber durch den steten Umgang mit Mendelssohn, der den Knaben wie ein Vater liebte und förderte, ward er gar bald ins Heiligtum der Kunst eingeführt, und fortan verwertete er sein künstlerisches Können lediglich zur vollendeten Wiedergabe wahrhafter Kunstwerke der Geigenliteratur.” [10]

In 1853, Reinecke was among the auditors in Düsseldorf when Joachim played Beethoven’s violin concerto under Schumann’s leadership at the thirty-first Niederrheinisches Musikfest. “Welch ein andrer, größerer war er inzwischen geworden,” Reinecke recalled. “Einst Gefolgsmann der Virtuosität, jetzt Priester der Kunst. […] Es ist ein müßiges Beginnen, so ein vollendetes Spiel mit Worten zu beschreiben. Aber noch heute, nach sechsundfünfzig Jahren, erinnere ich mich deutlich, daß ich nach diesem Vortrage mich in die einsamsten Gänge des Hofgartens schlich, um ungestört dieses künstlerische Ereignis noch einmal in meinem Innern zu durchleben.” [11]

Like others in the Mendelssohn/Schumann circle, Reinecke and Joachim shared a predilection for Classical composers and their compositions — for Bach, Mozart and Beethoven in particular. Reinecke went so far as to occupy himself with Joachim’s repertoire, preparing a piano reduction for an edition of Beethoven’s violin concerto, and arranging Bach’s Chaconne and a few other movements from Bach’s violin Sonatas and Partitas for piano solo. But Reinecke’s special love was Mozart: his advocacy for Mozart’s piano concerti was expressed in his 1891 book, Zur Wiederbelebung der Mozart’schen Clavierconzerte. Today, this advocacy may seem an innocuous enough undertaking, but in those days of musical party-spirit, it evoked considerable derision from the ranks of the Fortschrittspartei — and not in Germany alone. In the New York Evening Post, for example, we read:

“Carl Reinecke, late conductor of the Gewandhaus concerts at Leipsic, has written a brochure in which he pleads for the restoration of the Mozart concertos to our concert halls. In his conservative blindness he cannot see that those works are hopelessly antiquated. Reinecke has written more than 200 works, of which probably a dozen will survive him a decade or two. The works of conservative and reactionary composers (like Reinecke and Brahms) never live long, for genius means progress in an inflexible line of evolution.” [12]

Strongly influenced by Hegelian philosophy, the advocates of the neudeutsche Schule argued the cause of “progress” in the arts. For them, Mozart’s works represented, in the buzzword of the day, “einen überwundenen Standpunkt.” [13] Reinecke and Joachim, on the other hand, viewed the musical classics sub specie aeternitatis — that is to say, “from the standpoint of eternity,” as timeless expressions of spiritual truth. This is the sense of Joachim’s lines, jotted as a dedication in a book of Brahms lieder that Joachim gave to Agathe (Siebold) Schütte in the Autumn of 1894:

Nur das Bedeutungslose fährt dahin.

Was einmal tief lebendig ist und war

Das hat Kraft zu sein für immerdar. [14]

The two friends went so far as to share a mutual interest in the works of Spohr, though a less fashionable composer could hardly be found. In an undated letter, Joachim writes:

Lieber Reinecke!

Es hat mir leid gethan, Deinen Spohr-Erinnerungsabend nicht mitmachen zu können, da ich wirklich eine große Verehrung für ihn hege, und glaube er wird jetzt unterschätzt. Auch seine Zeit wird wohl wieder kommen, d. h. man wird sich unbefangener manches Herrlichen erfreuen, das er aus echtester Empfindung gesungen als jetzt möglich ist, wo starke Aufregungen und Geistreichelei an der Tagesordnung sind. [15]

Today, one might be tempted to apply Joachim’s words concerning Spohr to Reinecke and his violin concerto. Already in 1858, this seems to have been Eduard Hanslick’s view:

“Reinecke ist eine ungemein liebenswürdige künstlerische Natur. […] Mit der Technik der musikalischen Composition vollständig vertraut, würde er so gut wie mancher Andere die imponirenden Grimassen falscher Genialität ziehen, und sich damit zu einer gewissen Größe hinauflügen können. Daß er es verschmäht, und nur bedacht ist, dasjenige in reiner Form zu geben, was ihm die Natur echt verlieh, macht uns diesen Mann in dieser Zeit aufrichtig wert.” [16]

*

* *

This Classical, anti-virtuosic, orientation placed Reinecke and Joachim on one side of a significant aesthetic divide. It is customary today to separate violin concerti into two categories: virtuoso concerti and “symphonic” concerti. [17] Nineteenth-century virtuoso concerti include, for example, the works of Paganini, Ernst, Lipinski, Maurer, Wieniawski, Vieuxtemps, et alia, in which the technical and soloistic element predominates and is set in high relief against the tutti. To the other category belong concerti of Spohr, Mendelssohn, Bruch, Brahms, Dvorák and Chaikovsky: works in which the symphonic element plays a pervasive role, and in which the solo violin holds more-or-less constant dialogue with the tutti. Virtuoso concerti have much in common with operatic virtuosity and the art of embellishment. The symphonic style originates in the Classical works of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, and, as the term implies, shares a common history and aesthetic with the symphony itself.

Indeed, the history of the 19th century symphonic violin concerto closely reflects the troubled progress of the symphony during the same period. It is well-known that the generation that followed Beethoven had significant issues with the perpetuation of the symphonic form. Carl Dahlhaus famously wrote:

“Die symphonie, die durch Beethoven aus einer Gattung, die eine unbefangene Massenproduktion zuließ, zur “großen Form” geworden war […] geriet um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts in eine Krise, als deren sichtbares Zeichen die Tatsache erscheint, daß nach Schumanns Dritter Symphonie (1850), die chronologisch seine letzte ist, fast zwei Jahrzehnte lang kein Werk von Rang geschrieben wurde, das die absolute, nicht durch ein Programm bestimmte Musik repräsentiert. […] Um so auffälliger — und für Historiker, die in der Geschichte einer Gattung nach ungebrochener Kontinuität suchen, geradezu irritierend — ist die Tatsache, daß in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren mit den Werken von Bruckner und Brahms, Čajkovskij und Borodin, Dvořák und Franck die symphonie in ein ‘zweites Zeitalter’ eintrat, dessen Hinterlassenschaft heute, ein Jahrhundert später, immer noch einen großen Teil des Konzertrepertoires beherrscht.” [18]

Dahlhaus’s formulation was the subject of considerable discussion at the 1989 Internationales Musikwissenschaftliches Colloquium in Bonn, “Probleme der Symphonischen Tradition im 19. Jahrhundert.” [19] The history of the symphonic violin concerto may perhaps shed light on this discussion: first, because the composers who wrote them were by and large the same as those who cultivated the symphony, and second, because the symphonic violin concerto, while a related form of “serious” orchestral music, offered those composers a congenial alternative to the symphony — an alternative that allowed more lattitude for innovation in form and expression than the symphony, which by mid-century had become moribund, through its pretentions, its formal and aesthetic limitations, and the intimidating influence of Beethoven. The violin concerto therefore allowed the creation of at least a few symphonic “Werke von Rang” during the fallow decades of the symphony that Dahlhaus references.

The prime example of this is Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26 (1866), which likely served as an inspiration for Reinecke’s concerto in the same key. The first movement of Bruch’s concerto is unusual by any standard: a free introduction (Bruch uses the Wagnerian term Vorspiel) to the central slow movement that is the real raison d’être of the piece. Bruch had compunctions about whether a work in so unorthodox a form could properly fit the genre, but was reassured by Joachim:

“Auf Ihre ‘Zweifel’ freue ich mich Ihnen schließlich zu sagen, daß ich den Titel Concert jedenfalls gerechtfertigt finde — für den Namen ‘Phantasie’ sind namentlich die beiden letzten Sätze zu sehr und regelmäßig ausgebaut. Die einzelnen Bestandtheile sind in ihrem Verhältnisse zu einander sehr schön und doch contrastirend genug; das ist die Hauptsache. Spohr nennt übrigens auch seine Gesangs-Scene ‘Concert’”! [20]

It is precisely this freedom — this ability to break free of the shadow of Beethoven and “großer Form” while resting on the authority of accepted models — that appealed to composers of a conservative bent and allowed the symphonic violin concerto, as a form of absolute music, to maintain a provisional hold on the public at a time when the symphony itself was in eclipse. As Joachim mentioned in his letter, Spohr provided an early example of unconventional form — a concerto in the form of an operatic scena. Mendelssohn’s concerto (1845), which influenced subsequent composers as late as Sibelius, is replete with formal innovations (the lack of opening tutti, the centrally-placed cadenza in the first movement, the unusual recapitulation in the first movement, etc.). Equally important, later composers also felt freer in the violin concerto to explore certain more lyrical or characteristic moods — moods that were congenial to the era, but that lay outside the aesthetic norms of the symphony, or were problematic if subjected to the formal processes expected in the symphony post-Beethoven. Thus, while characteristic symphonic works such as Goldmark’s Ländliche Hochzeit Symphony (1876) once enjoyed a protracted period of popularity, they are no longer frequently performed. Similarly conceived concerti such as Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole or Bruch’s Schottische Fantasie, on the other hand, continue to be staples of the violinist’s repertoire.

Symphonic Violin Concerti in the 19th Century

1806 Beethoven Concerto in D major, op. 61 (Joachim)

1816 Spohr Concerto no. 8 in modo di scene cantante, op. 47 (Joachim)

1834 Berlioz Harold en Italie (performed by Joachim under Berlioz)

1844 Mendelssohn Concerto in E minor, op 64 (Joachim, 2nd performance)

1853 Schumann Concerto in D minor WoO 23 (withheld) (dedicated to Joachim)

1853 Schumann Fantasie op. 131 (dedicated to Joachim)

1857 Hiller Concerto in a A major, op. 152 (dedicated to Joachim)

1861 Joachim Concerto no. 2 in D minor, op. 11 Hungarian (Joachim)

1867 Bruch Concerto no. 1 in G minor, op. 26 (dedicated to Joachim)

1874 Lalo Symphonie Espagnole (written for Sarasate)

1875 Joachim Concerto no. 3 in G major, WoO (Joachim)

1876 Reinecke Concerto in G minor, op. 141 (dedicated to Joachim)

1877 Damrosch Concerto in D minor WoO (dedicated to Joachim)

1877 Dvořák Romanze in F minor, op. 11 (dedicated to Ondříček)

1877 Goldmark Concerto in A minor, op. 28 (Lauterbach)

1878 Brahms Concerto in D major, op. 77 (dedicated to Joachim)

1878 Bruch Concerto no. 2 in D minor, op. 44 (dedicated to Sarasate)

1878 Chaikovsky Concerto in D major, op. 35 (dedicated to Brodsky/ Auer/ Halíř)

1879 Dvořák Concerto in A minor, op. 53 (B. 108) (dedicated to Joachim/ Ondříček)

1880 Bruch Schottische Fantasie, op. 46 (dedicated to Sarasate)

1880 Niels Gade Concerto in D minor, op. 56 (dedicated to Joachim)

1880 Saint-Saëns Concerto in B minor, op. 61 (dedicated to Sarasate)

[Names in parentheses indicate that the works were either written by, dedicated to, premiered by, or predominantly championed by those players.]

The foregoing table demonstrates the dominance that Joachim had over the whole genre of symphonic violin concerti in the 19th century, approached only, from the 1870s onward, by Pablo de Sarasate. Even Beethoven’s concerto would have sunk into obscurity, had not the young Joachim revived and championed it. Joachim learned Mendelssohn’s concerto from its composer — he was the second violinist to play it, contemporaneous with David. He also played Harold in Italy under the composer’s baton, whereas Paganini, who commissioned the work from Berlioz, never played it, claiming the viola part was lacking in virtuosity, and insufficiently prominent. The works of Schumann and Spohr likewise belonged to Joachim’s repertoire. It is telling that Joachim never played the concerti of Ernst, Wieniawski or Vieuxtemps, although he was friendly with their creators, and valued them highly both as violinists and as men. Though he was a great virtuoso, Joachim eschewed violinistic fireworks. More than any other 19th century violinist, he was responsible for promoting the violin concerto as a “serious” form — in the sense of the Leipziger res severa — that, in its expressive possibilities, could stand comparison with the symphony.

Reinecke’s concerto reflects his sympathy with Joachim’s project: he worked within the traditions of the symphonic concerto, anticipating and advancing the revival of the genre. Viewing this table, one might argue that Reinecke’s concerto, far from being “reactionary,” was a harbinger, not only of a zweites Zeitalter of symphonic violin concerti, but of a goldenes Zeitalter. The subsequent four years alone saw the appearance of the canonical concerti of Goldmark, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Dvořák, Bruch (Schottische Fantasie), and Saint-Saëns.

The third movement of the work will serve briefly as an example of Reinecke’s poetic, anti-virtuosic conception, expressed with the innovative freedom of form that is characteristic of the 19th-century symphonic violin concerto, generally. The entire concerto is strongly reminiscent in tonality, mood, and theme of Bruch’s popular Concerto no. 1 in G minor, and, like the Bruch, it seems to glory in its elegiac slow movement as its real reason for being.

Instead of following that movement with the customary light, brilliant rondo finale, Reinecke has given us an expressive movement of a lyrical, cantabile, character — a series of developing variations, closely related to, and at times recapitulating, the theme of the slow movement. Of it, a contemporary critic wrote that “der Finalsatz viel zu weitschichtig angelegt und mit zu wenig Rücksicht auf klar übersichtliche Gliederung seiner Theile ausgeführt ist.” [21] This seems a mis-hearing of the work, however, for the movement can be understood as a rather traditional sonata-rondo form (or what might better be described with James Hepokoski’s term: a “sonata-rondo deformation”), as this analytical diagram shows:

A short transition, such as one finds in Beethoven or Mendelsson, introduces the movement. The main theme, a broad amabile, demonstrates the double stop technique for which Joachim was famous in his time. It is difficult to play, but not virtuosic in character. The recursive nature of the theme creates a somewhat too-static impression at the start of a movement that is conceived in a similarly recursive form. The “A” theme alternates with a contrasting, arpeggiated, “B” theme, the character of which is strongly reminiscent of Schumann. The “C” group can be heard as a variation or development of the “A” theme — further contributing to the recursive nature of the movement.

A short transition, such as one finds in Beethoven or Mendelsson, introduces the movement. The main theme, a broad amabile, demonstrates the double stop technique for which Joachim was famous in his time. It is difficult to play, but not virtuosic in character. The recursive nature of the theme creates a somewhat too-static impression at the start of a movement that is conceived in a similarly recursive form. The “A” theme alternates with a contrasting, arpeggiated, “B” theme, the character of which is strongly reminiscent of Schumann. The “C” group can be heard as a variation or development of the “A” theme — further contributing to the recursive nature of the movement.

An interesting feature of the movement is the presence of two dramatic, symmetrically placed D major scales that function as audible orientation points within the overall structure. Symmetric, as well, are two short, rather brilliant developments: one in double stops, and the other in triplets. The most interesting feature of the movement, however, is the threefold return of the main theme from the second movement — each time varied and ornamented — first in E, then in F, and finally in the tonic G major. These tonally progressive “reminiscences,” which function as interruptions (or “deformations”) of the Rondo, emphasize the familial relationship between the last movement “A” and “C” themes, and the main theme “X” of the lyrical slow movement. Thus, the entire third movement can be understood as a continuation, or development, of the second movement. The deformation of the standard sonata-rondo form through lyrical reminiscences serves an expressive purpose that carries the piece far from mechanical, “empty,” virtuosity into the world of Schumannesque poetry.

According to Joseph von Wasielewski, Reinecke’s Violin Concerto deserves, “in musikalisch künstlerischer Hinsicht unstreitig ein hervorragender Platz in der Geigenliteratur, wenn auch die Principalstimme nicht mit bestechender Brillanz ausgestattet ist. Reinecke hat es sich offenbar angelegen sein lassen, mehr die solide Seite als die virtuosenmäßige Bravour des Geigenspieles hervorzukehren.” Wasielewski hints at the work’s fatal weakness — as well as, potentially, its most ingratiating attribute — when he continues: “Wer das Werk von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus betrachtet wird seine Freude daran haben.” [22] In any case, Reinecke’s violin concerto is an attractive work that despite, or perhaps even because of, its previous neglect would provide a welcome alternative in the violinist’s repertoire to Bruch’s all-too-frequently performed masterpiece. It also provides a valuable insight into the musical friendship between two important 19th-century performer/composers and their relationship to aesthetic trends in European symphonic music at a critical point in its development.

© Robert W. Eshbach, 2014

[1] Recorded at the Grosser Saal, Kultur-Casino Bern, Johannes Moesus, conductor, 09/23/2004 and 09/24/2004; released 04/24/2007 on the CPO label, no. 777 105-2, ISBN 761203710522.

[2] Reinecke: “David hatte das Werk übrigens eigenmächtig in solcher Weise zugestutzt, daß ich förmlich erschrak, als ich die Partitur später zurückerhielt. Es war eine Schwäche von David, daß er alles für seine, vielleicht etwas eigenseitige Technik umarbeitete und sich auch anderweitige Eingriffe in die Komposition anderer erlaubte.” Carl Reinecke, Erlebnisse und Bekenntnisse, Doris Mundus (ed.), Leipzig 2005, p. 102.

A review of the October 3 concert appeared in the Wiener Zeitung, October 14, 1858: “Aus dem am 3. d. M. stattgefundenen ersten unserer ‘großen Konzerte’ nenne ich als besonders bemerkenswerth die Solovorträge unseres Konzertmeisters Ferdinand David. Derselbe führte uns ein neues noch im Manuskript vorliegendes Violinkonzert von dem talentvollen jungen Tonsetzer Karl Reinecke und den bekannten Tartinischen Teufelstriller vor, das Erstere eine in der That anmuthende Novität von solider Arbeit.”

[3] Johannes Joachim and Andreas Moser (eds.), Briefe von und an Joseph Joachim (2/3), Berlin 1912, pp. 1-2.

[4] Signale für die musikalische Welt, vol. 35, no. 3 (January 1877) p. 35.

[5] Musikalisches Wochenblatt, vol. 8, no. 2 (5 January 1877), p. 21.

[6] Kiel, 24 June 1878. Vide: Signale für die musikalische Welt, vol. 36, no. 43 (September 1878), p. 681.

[7] — Reinecke, Erlebnisse und Bekenntnisse, p. 260.

[8] — ibid., p. 25.

[9] Though this bias, on Joachim’s part, may have been as much an image as a reality. His wife, Amalie, claimed in a letter: “Unparteiische Richter welche genug von Violine verstünden müßten ihm auch als Techniker die erste Stelle zuweisen. Ich habe oft genug ihn, seine Art einzelne Stellen zu spielen mit der Art Sarasate’s u. Anderer vergleichen können u. stets gefunden, daß er alles größer, kühner u. feuriger vorträgt — auch ‘Virtuosenstückchen’ kühner u. eleganter spielt, als die andern, wenn er dies freilich nur für sich allein in seinem Studierzimmer vollbringt — weil er öffentlich sich nur als Priester des Allerschönsten u. Höchsten zeigen will.” [Beatrix Borchard, Stimme und Geige: Amalie und Joseph Joachim, Biographie und Interpretationsgeschichte, Wien 2005, p. 502.]

[10] — Reinecke, op. cit., p. 261.

[11] — ibid., pp. 261-262.

[12] Public Opinion, vol. 20, no. 16 (16 April 1896), p. 500.

[13] Hans von Bülow, for example, never performed a Mozart concerto in public. [Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen, Musikalische Interpretation Hans von Bülow, Stuttgart 1999, p. 24.]

[14] Emil Michelmann, Agathe von Siebold: Johannes Brahms’ Jugendliebe, Göttingen 1929, p. 318.

[15] Unpublished letter, private collection.

[16] Eduard Hanslick. Sämtliche Schriften. Historisch-kritische Ausgabe, Dietmar Strauß (ed.), Band I, 4: Aufsätze und Rezensionen 1857-1858, Wien 2002, pp. 359-360.

[17] I use this term in a somewhat freer manner than is customary.

[18] Carl Dahlhaus, Die Musik des 19. Jahrhunderts, in: Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, C. Dahlhaus (ed.), vol. 6, Wiesbaden 1980, p. 220.

[19] Vide Kongreßbericht: Probleme der Symphonischen Tradition im 19. Jahrhundert, Siegfried Kross (ed.), Tutzing 1990.

[20] — Joachim and Moser (eds.), Briefe von und an Joseph Joachim (2/3), p. 393.

[21] Musikalisches Wochenblatt, vol. 8, no. 2 (5 January 1877), p. 21.

[22] Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski, Carl Reinecke. Sein Leben, Wirken und Schaffen, Leipzig n.d., p.85.