The Monthly Review, No. 20 (May, 1902): 80-93.

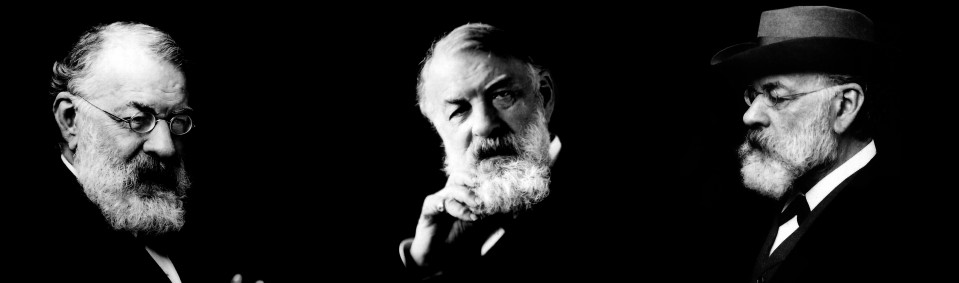

Joseph Joachim: Maker of Music

In the language of their own age the greatest artists speak for all time; which is as much as to say that they do not speak merely for posterity, and that they may be as far beyond the comprehension of a later age as they were beyond that of their own. The works of Palestrina and Shakespeare (to take the most widely different examples) were greeted by their contemporaries with an intelligent sympathy of which hardly a trace appeared in posterity until comparatively recent times; and even in cases like that of Beethoven, where there seems to have been a century of steady progress in the understanding of his work, it is rather humiliating to reflect how much of our superiority over our ancestors is merely negative. Beethoven was surrounded by brilliant musicians who worked for their own time and had not a word to say to us. Our ancestors had to single Beethoven out from that dazzling crowd; but we have little more than vague ideas as to who was in the musical world a hundred years ago besides the venerable Haydn, then penning his last compositions, and Schubert, Weber, Cherubini, Spohr; in short, precisely those men who are too great and typical to be compared with each other. And in so far as we are thus incapable of realising what it was in these great artists that was too new for their contemporaries to understand, we lose a certain insight which their comparatively few intelligent supporters possessed in an eminent degree, and we fall into the error of greatly under-estimating the difficulty of classical art for ourselves. Indeed, an intelligent sympathy with great art is a privilege that is in all ages hardly won and easily lost. It is not the privilege of experts, nor even of remarkably clever people; it probably needs nothing beyond the sensibilities necessary for the enjoyment of the art, controlled by such clearness of mind as will save us from the unconscious error of setting ourselves above the greatest artists of the present in the past. It is astonishing how many disguises this error assumes; and it often has no more connection with conceit than bad logic has with fraud. The expert is always in danger of reasoning as if his fund of recent technical and aesthetic knowledge had raised his intellect to a higher plane than that of the great men of an earlier generation; the student is constantly mistaking the limitations of his own technique for laws of art, and doubting whether this or that in a great work is justifiable when he ought simply to realize that it is a thing he cannot possibly do himself; and (most insidious of all such confusions of thought) many persons of broad general culturre allow their own legitimate pleasure in a work of art to be spoilt by the consciousnes that there is so much that they do not understand; as if it were an insult to their intelligence to suppose that any work of art should be too great for them to grasp at once.

These very obvious considerations seem to be more neglected in the criticism of performances than in that of compositions; yet it would seem that the very great performer must be almost as far beyond his own age as the very great composer, with the disadvantage that his playing cannot survive him to meet with more justice from posterity. The object of the present sketch is to describe the permanent element in the life-work of one whom most persons of reasonably wide musical culture and knowledge believe to be probably the greatest interpreter of music the world has ever seen. It may seem a strained figure of speech to call the greatness of Joachim’s playing a permanent quality, except in the sense that it has more than stood the test of time as measured by his own career of over sixty years of unbroken triumph; but there can be no doubt that the influence of such playing on subsequent art, both creative and interpretive, must continue to be profound and vital long after the general public can trace it to its source in the personality of the great artist who originated it. The immortality for which the greatest artists work is a thing of fact rather than of fame. Bach wrote his two hundred odd cantatas, sparing no pains to make them as beautiful as only he could understand music to be; yet he not only knew that there was no prospect of their becoming known outside his own circle during his life-time, but he cannot even have a consoled himself with the hope of an immortality of fame for them afterwards; unless we are to suppose that he foresaw such a glaringly improbable thing as their publication by the Bach-Gesellschaft on the Centenary of his death! To such minds facts are facts even if the world forgets them, the artist aims at nothing but the perfection and growth of his art. He cheerfully uses it to earn an honest living, and nothing of human interest is too remote to be material for his art; but he remains undeterred by all that does not affect the matter in hand. The desire for fame, contemporary or posthumous, as an end in itself, can no more explain the cantatas of Bach or the playing of Joachim than the desire for wealth or popularity. All men desire these things, for ulterior purposes, and many great men attain them; but to an artist the actuality of artistic production will always override all considerations of what the world will say or do when the work is finished. In extreme cases the artist is even blameworthy in his indifference to the fate of his work, as when a great painter is heedless in the use of his colors that are not permanent.

Joachim’s unswerving devotion to the highest ideals of the interpretation of classical music is a striking illustration of this rigorous actuality in the true artist’s guiding principles. A composer must have more serious purpose than the normal man of talent if he persists in doing far more careful and copious work than practical purposes demand, while he is all the time convinced, as Bach must have been, that this work will never become known. And this is yet more obviously true of a player; even if it be happily the case, as it certainly is with Joachim, that his efforts have met with the warm gratitude of the public throughout the whole musical world. Indeed, Joachim’s success is as severe a test as his playing could possibly have had; for popular success cannot encourage an artist not absorbed in the realisation of pure artistic ideals to maintain his playing at a height of spiritual excellence far beyond the capacity of popular intelligence. At the present day it is as true as it always has been, that a student of music can measure his progress by the increase in his capacity to enjoy and learn from the performances of the Joachim Quartet: just as a scholar can measure his progress by his capacity to appreciate Milton. Here, then, we have work perfected for its own sake; work that must have been even so perfected if it had never been rewarded as it has been, or surely of all roads to popularity that which Joachim chose—the road of Bach and Brahms—was the most unpromising. The immortality of fact, not of name, is the only principle which will explain Joachim’s career; indeed, it is the only explanation of his popular success. , For, as it is sometimes pointed out with unnecessary emphasis, he has attained his threescore years and ten; so that it is absurd to suppose that his present popularity can still spring either from the novelty of scope, which was once the distinguishing feature of his as of other remarkable young players’ technique, or from that capacity for following the fashion which he never had and never wanted. It is the permanent and spiritual element that makes his playing as profoundly moving now as it was in his youth, and that would remain as evident to all that have ears to hear, even if what is sometimes said of his advancing age were ten times true. As a matter of fact, Joachim’s energy is that of many a strong man in his prime. I believe it cannot be generally known in England what an enormous amount of work he continues to do every day, apart from his concert-playing As the original director of the great musical Hoch-Schule in Berlin, he continues to fill out his working-day with teaching, conducting, administering, and examining; while his numerous concerts, which we in England are apt to regard as the chief, if not the only, demand on his energy, are given in the intervals of this colossal work of teaching by which he has become a maker of minds no less than of music. His concert season in England—those few weeks crowded with engagements that leave barely time to travel from town to town to fulfil them—is in one sense his holiday; and while there are no doubt plenty of young artists who would be very glad of a fixed position in a great musical Academy as a kind of base of operations for occasional concert tours, there are probably few who would not shrink from devoting themselves in old age to both these occupations as Joachim continues to devote himself at the present day. And his vigour seems, to those who have followed his work during the last eighteen months or so, to have increased afresh; certainly nothing can be less like the failing powers and narrowing sympathies of old age than his constant readiness to help young artists not only with advice and encouragement, but by infinite patience in taking part with them in their concerts. If all that he has done in such acts of generosity could be translated into musical compositions, the result would be like Bach’s “fünf Jahrgänge Kirchen-cantaten,” five works of art for every day in the year. In the presence of such an age it is the failings of youth that seem crabbed and unsympathetic. In boyhood the friend of Mendelssohn, whose wonderful piano-forte playing he can at this day describe to his friends as vividly as he can interpret Mendelssohn’s violin concerto to the world at large; in youth the friend of Schumann, to whom he introduced his younger friend, Brahms; throughout life the friend of Brahms, whom he influenced as profoundly as Brahms influenced him; and in middle age one of the very first and most energetic in obtaining a hearing for the works of Dvoràk: a man of such experience might rather be expected to become in the end a laudator temporis acti, with little heart to encourage the young. But Joachim was not born in 1881 that his experience might be useless to those who begin their work in the twentieth century: and there is no man living whose personal influence on all young artists who come into contact with him is more powerful or leaves the impression of a deeper sympathy.

It is not my intention to repeat here the glorious story of Joachim’s career; his leading part in the building up of practically the whole present wide-spread public familiarity with classical chamber-music, including that of Schumann and Brahms; the remarkable history of his early relations with Liszt and Wagner at Weimar, so will set forth in Herr Moser’s recent biography of Joachim, and so entirely different from the crude misunderstandings of the typical anti-Wagnerian; or even the list of illustrious pupils who prove that Joachim’s labour of love in the Hoch-Schule is not in vain. On the other hand, of Joachim the composer I have something to say, more especially as that is a capacity in which he has met with very scanty recognition; perhaps chiefly because his works are as few as they are beautiful, for music is not, like precious stones, famed in proportion to its rarity. Three concertos, five orchestral overtures (of which two are still unpublished, while the exquisitely humorous and fantastic Overture to a Comedy by Gozzi, though composed in 1856, has only just now appeared); these, with a moderately large volume of smaller pieces, such as the rich and thoughtful Variations for viola, and the later set for violin and orchestra, and several groups of pieces in lyric forms, are a body of work that is more likely to escape to preoccupied attention of the present age than that of the posterity that will judge of our art by its organization rather than by its tendencies. Perhaps we may hope for a more immediate recognition of the beauty of the newly published Overture to a Comedy by Gozzi; for its humour and lightness are a new revelation to the warmest admirers of Joachim’s compositions, while it is second to none in perfection of form.

But let us turn from this subject for a moment to consider what is the real attitude of the public with whom Joachim as an interpreter is so popular. It is absurd to suppose that the public can completely understand the greatest instrumental music; that there is not much in the works of the great classical composers that is at least so far puzzling to them that they would prefer a course or one-sided interpretation to such a complete realization of the composer’s meaning as Joachim gives. But fortunately the typical representative of the intelligent public is not the nervous and irritable man of culture who is always distressing himself because he cannot grasp the whole meaning of a great work of art. The inexpert, common-sense lover of music, who represents the best of the concert-going public, never supposed that he could. All that he demands is that on the whole he shall be able to enjoy his music, and, unless it is exceptionally unfamiliar to him, he can generally enjoy a great part of it almost as intelligently as a trained musician, and often far more keenly, since he is less likely to suffer from over-familiarity with those artistic devices that mean intense emotion in great art and mere technical convenience in ordinary work. No doubt, the ordinary inexpert listener often fails to understand what is it once great and specially new to him; otherwise Bach would have been recognised from the outset as a profoundly emotional and popular composer. And, on the other hand, without the experience of constantly hearing the finest music even an intelligent man may easily be deceived into admiring what is thoroughly bad: indeed, it is a common place of pessimistic critics to point out that the audience the crowds a great hall to hear Joachim has been known in the very same concert to encore songs of a character altogether beneath criticism. But we often over-rate the importance of such things. The public does not claim to be able to tell good from bad; it simply takes considerable trouble to enjoy what it can, being in that respect far more energetic and straightforward than many of those who would improve its taste. And if it often shows that it enjoys many things merely because it is not found out how horribly false they are, that is no proof whatever that its enjoyment of great art is spurious. No doubt it is sad to be victimised by false sentiment; but surely it is good to be stirred by true enthusiasm; and that the public can be so stirred without the smallest concession being made either to its ignorance or its sentimentality the whole of Joachim’s career triumphantly testifies. Since the time of Handel it is probable that no musician devoting himself exclusively to the most serious work in his art has approached Joachim’s record of a continuous popularity rising yet, after more than sixty years, to new triumphs that excite the wonder of many whose interest in music is of too recent growth for them to remember what enormous influence he has always had on his contemporaries and juniors, or to realise that many things now regarded as of quite a new and even anti-academic school owe their vitality to the tradition which he has established. Surely the public that has learnt so well to recognize and testify to the greatness of such a life deserves forgiveness for many temporary errors of taste. It is more important to love good art than never to be deceived by bad.

In the face of Joachim’s universal popularity, the accusations of “cold intellectuality” which of been every now and then directed against him by those whose ideal of art is the greatest astonishment of the greatest number, are not only signs of second-rate criticism but libels on the public. If there is one thing in which the public is almost infallible in the long run, it is in detecting a lack of warmth in work that claims to be serious and solid. No assault on the public’s feelings is too brutal (as Stevenson said of “Home, sweet Home!”), in other words, no sentiment is too false for popular success; but on the other hand no apathetic solidity is imposing enough to interest the public which suspects that it has not interested the artist himself. Indeed, the public is severe in its sensitiveness to the difference between things done as the direct result of an intimate knowledge and love of the work in hand and the very same things as done simply because So-and-so does them. But, on the other hand, it does not readily fall into the error of demanding that no two artists shall have the same “reading “of a composition. When a man of good sense without musical training troubles to think about “readings” at all, the idea that a “reading” is the worse for occurring to a dozen great artists in different generations is the last thing to enter his head. There is no reason why pupils should fail to become great artists because they have learnt all that they know of the interpretation of great music from such a man as Joachim; what art needs, and what the public has the sense to demand, is that they shall so play because they so understand and feel. It does not then always follow that the public will give such work its due; but it is certain that where the artist has not thus made his master’s knowledge and feeling his own, the public will not be deluded into believing that he has. Even the mere virtuoso must have some pleasure in his own virtuosity, or the public will have none. And it is probably sheer tenderness of conscience that causes the universal popularity a false settlement; no one feels comfortable in refusing to respond when his feelings are appealed to by those his claims he has no means of refuting, and this is precisely the position of the inexpert listener with regard to sentimental music.

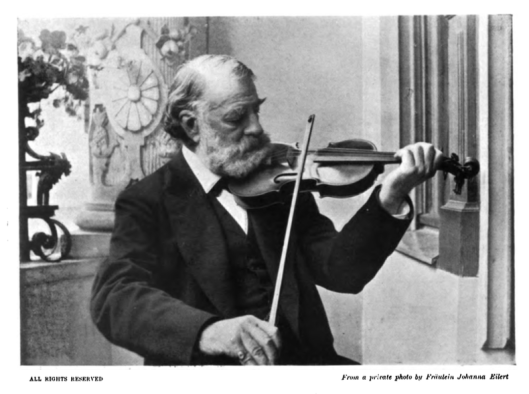

Much has been written in praise and illustration of Joachim’s playing and that of his quartet; and from most points of view it has been so well and so recently described, both in England and abroad, that to say more here would be impertinent. One point of view has, however, been somewhat neglected. I am not aware that Joachim’s playing has been expressly reviewed as the playing of a composer; and I therefore proposed to devote the rest of the sketch to a few observations on the largest and best known of his works, the Hungarian Concerto, drawing some parallels between it and his playing, and thus illustrating how his sympathy with the great composers has come from a share in their creative experience.

The concerto is on an enormous scale; the first and last movements are, if I am not mistaken, the longest extant examples of well-constructed classical concerto form. And that the form is of classical perfection no one who has carefully studied the work can deny; indeed, so convincing and natural is the flow, and so are the contrasts, that the length of the work remains quite unsuspected by the attentive listener, and would probably never be discovered at all but for the necessity of sometimes timing the items of concert programmes. One may imagine that the composer who shows such colossal mastery of form, would see to it that his playing of classical music revealed the proportions of all that he played, and that he would never dream of “bringing out the beauty” of this or that passage by playing it as slowly as if it belonged to quite a different movement from that in which it occurs. This is, indeed, a tempting short cut to impressiveness of effect; in fact, many fine artists have spared no pains or thought in the search for fresh passages in classical music that can be so revealed to the public; and at all times there has been a definite school of criticism that regards such a method as the true way of artistic progress. It must also be candidly confessed that the higher criticism ruins its own cause when it accuses such artists of false sentiment or vulgarity, or anything more reprehensible than the failure to recognise how much of the greatness of art lies in proportion and design. A sense of form, such as is shown in the Hungarian Concerto, is almost the rarest thing in art, and is incomparably the highest of technical faculties. If Joachim had not been capable of composing a work thus worthy to take a place among the great classical concertos, he would not have been able as a player to found that great tradition of interpretation that has made the last quartets of Beethoven on the whole better understood by the musical public than Shakespeare is by the average reader. The tradition, once founded, can be nobly carried on by players who have no thoughts of composition; but to originate such a work requires an essentially creative mind. No amount of exploration from point to point, or loving care in the delivery of each phrase, no genius for breadth and dignity of musical declamation would ever have sufficed to make these works, so unfathomable in detail, grandly intelligible as wholes. And unless the whole is grasped, the details remain undiscovered.

Of course this grand quality of form is not directly recognisable by the public, either in compositions or in performances. It is a cause rather than an effect, and it is absolutely unattainable by mere imitation. Nor is a school-knowledge of the general facts of classical form equivalent to this true grasp of musical organisation, either in playing or in composition; for these general facts, just in so far as they are general, are accurately true of no one classical work. They are not the principles that make classical music what it is; they are the average phenomena that enable us to define and classify art-forms: and that kind of playing that carves the music joint byjoint, that treats a fugue as if nothing but the fugue-subject were fit for the public ear, and that always plays a specially beautiful phrase louder and slower than its context, —— such playing is as far removed from Joachim’s method of interpretation as the form of a bad degree-exercise is from that of the Hungarian Concerto.

There is nothing scholastic or inorganic in Joachim’s form; perhaps in the first movement one has a temporary impression of rather cautious symmetry of rhythm, just as one has with the first movement of Beethoven’s Concerto in C minor, a work that in formal technique and proportions is remarkably akin to Joachim’s and probably influenced it more powerfully than the entire absence of resemblances in external style and theme would suggest. But, like the Beethoven C minor, the Hungarian Concerto soon shows that it is not of such matter as can be cast in a merely academic mould. Though in both works the opening tutti, with its deliberate transition from first subject to second, is more like the beginning of a symphony than either Beethoven or Brahms allowed in the tuttis of their later concertos to be, yet the treatment of the solo instrument, its relation to the orchestra, and the grouping and development of the themes, are in both works as mature and highly organised as pollible, and as surely the work of a great composer in Joachim’s case as in Beethoven’s. The very outset of Joachim’s first solo, where the violin passes from the impressive first theme to allude to the tender sequel of the second subject, a phrase originally uttered in the major mode by the oboe in its poignant upper register, but now given in the minor mode with the solemn tones of the violin’s G-string; this is just such a freedom of form as only a true tone-poet can invent. Classical music is full of such things; ordinary formal analysis cannot explain them, since, as we have seen, it is concerned with averages, not with organic principles; and these passages have no external peculiarity to call the attention of the inexperienced to their significance. If there is much of this kind in classical music that is now of common knowledge, if it is possible to point out such things here, this is mainly due to the fact that the most influential musical interpreter of modern times can reveal the meaning of such traits because he has experienced them In his own creative work.

All that has been said here as to the form of the Hungarian Concerto and its analogy with the architectonic quality of Joachim’s playing may be repeated in different terms as to the more detailed aspects of the work. The score is so full of detail that it is very difficult to read; not that there is anything startlingly “modern” about it; those who would seek in it the “latest improvements of modern orchestration” are doomed to disappointment. For one thing, it was written within two years of Schumann’s death, eighteen years before the appearance of Brahms’ first symphony, and twenty years before Dvoràk came to his own (largely through the united efforts of Brahms and Joachim themselves). The only modern influence that could possibly affect a work in so classical a form at the date of this concerto was to be found in Brahms, to whom, in fact, the work is dedicated. But at that time Brahms was twenty-four and Joachim was twenty-six; and the history of the opening of Brahms’ B♭ sextet and many things in his first pianoforte concerto will bear witness that the influence was about equally strong on both sides. However, all such historical matters are beside the mark. Joachim, both as composer and player, is an immortal whose work is so truly for all time that it cannot be measured in terms of the present or any age. The Hungarian Concerto may perhaps seem, to some who put their trust in symphonic poems, almost as antiquated as Bach’s arias and recitatives seemed to most musicians in the ‘fifties just a century after Bach’s death; but a time always comes, even though centuries late, when it is recognised that in art all “effects” must have their causes no less than in logic and nature; and that the work in which the effects come from sufficient and deep-rooted causes has more vitality than that which depends merely on brilliant allusions to the latest artistic discoveries of its day.

When the time comes for the verdict of history as to the instrumental music of the last sixty years, Joachim will still be known as a purifying and ennobling influence of a power and extent unparalleled in the history of reproductive art; but I cannot believe that historians will ascribe this influence merely to the violinist; and they will see in the enormous wealth of a harmonious detail that crowds the score of the Hungarian Concerto that very completeness and justness that we know so well in his playing. When they admire the art with which the solo violin is made to penetrate the richest scoring with ease, they will understand, perhaps better than ourselves, that true balance of tone and perfection of ensemble with which the Joachim Quartet quietly and simply discloses all essential points without reducing the accompaniment to a dull, disorganised mumble. When they see the wonderful burst of florid figuration that accompanies the return of the theme of the slow movement, or the freedom and subtlety of its coda, they will hear what it was in Joachim’s playing that showed us the true depth of expression in Bach’s elaborately ornate melody, which our fathers thought so antiquated and rococo. And they will long to have heard Joachim’s violin-playing as we long to have heard Bach at his organ: not from curiosity to verify an old record of technical prowess, but from the desire to recover the unrecorded manifestations of a creative mind.

DONALD FRANCIS TOVEY.