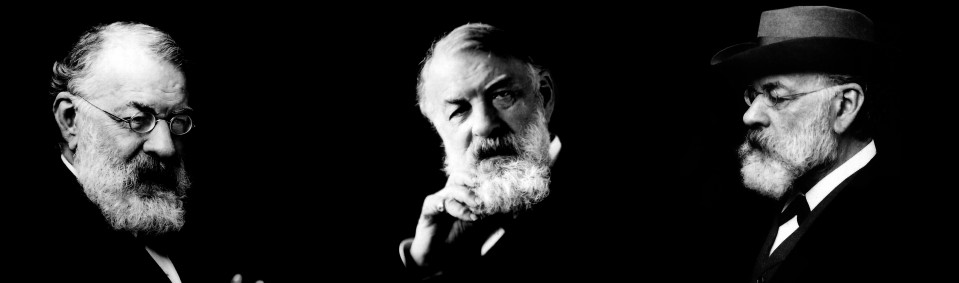

From Donald Francis Tovey, “Performance and Personality,” London: The Musical Gazette (March, 1900) pp. 17-21; (July, 1900), pp. 33-37; p. 43 (letter).

Donald Francis Tovey

Portrait by Philip Alexius de László (1913)

© The University of Edinburgh Fine Art Collection

Supplied by the Public Catalogue Foundation

II

[…] We have all heard with feelings of great disappointment that Dr. Joachim is not to visit us this spring; and it is with far deeper feelings than disappointment that we learn that it is the state of his health that deters him. While we anxiously wait in the hope of learning that his appearance here is perhaps only delayed until the summer’s warmth and brightness bring him back to us in May or June, our duty to him, to ourselves, and to all whom we may influence is as plain as ever. We must try to realise what it is that we miss during this spring concert-season, and we must use that realisation as a touchstone by which to criticise other players and performances, not so much by revealing their shortcomings as by trying to find out how often and how far they have a share in that greatness which we call to memory. And when he returns to us after this delay we must welcome him with an admiration and sincerity so much the deeper as it is more definite; we must cease to be content with the vague and lofty phrases about “breadth” and “tradition” and “intellectuality,” and other beautiful but indefinite terms which we are so apt to join without sense of incongruity to such frigid and patronising encomiums as “masterly,” “well-nigh faultless,” &c. The gravest defect of our present-day musical criticism is surely the vagueness of our praise, a vagueness from which the lightest word of blame stands out with startling blackness, and makes whole columns of unimpressive superlatives read almost like sarcasm. Let us try to use this somewhat melancholy opportunity that is now open to us — the opportunity of searching our memories for an impression dim enough for us to analyse, while the dazzling reality that dims our vision and paralyses our utterance is absent.

That Dr. Joachim was in my mind last December when I tried to describe the ideal great veteran, has long ago been obvious to every reader. That being so, let us proceed to add further details to the portrait. One of the first questions that suggest themselves when we try to estimate the greatness of a player is: What is the range of his sympathies? Can he enter into the spirit of all the great music in which he can possibly take part; and if not, what are his limitations? In answering these questions we must bear in mind the important fact that it is one thing to live through the whole growth and rage of a stormy artistic controversy, and a very different thing to grow up in a period when that controversy has almost entirely died out. And when such a controversy lies very largely outside one’s one special sphere of activity, and when it is as clear as noon that during the height of the controversy to take the “progressive” side means utter distraction and ruin to one’s own work, while to continue aloof working on the old footing means a sure growth in mastery, sympathy and ideality with no less certainty of becoming quite as unpopular and beyond the ordinary intelligence of critics as the most violent partisans of the “new school;” why, then, this latter course is surely the only courageous and sensible one for a great artist to take. We surely do not regret that he has not thrown his energies into work which would only swamp them without gaining from them anything like what they will yield us if allowed to develope in their own way. Still less dare we imagine that he might have shewn broader sympathies by taking a course of vague compromise. An artist is not great if the discovery that certain tendencies are fatal to his work does not thoroughly estrange him from those tendencies; and he is not honest if, when asked his opinion, he does not boldly proclaim his estrangement.

These considerations should help us to understand that Dr. Joachim’s uncompromising repugnance to the art of Wagner is a matter for which apology would be an impertinence. Whether we hold with Wagner or not (I for my part write as a Wagnerian, if a sound appreciation of Brahms and older classics is not a disqualification), we cannot reflect on the mental and artistic wreckage caused by the rabid Wagnerianisms and Anti-Wagnerianisms of the past without deepening our reverence for the great violinist who, in the height of the storm and while yet at a time of life when violent enthusiasms are apt to hurry the mind away to lose itself in one or the other extreme of barren pedantry, boldly chose to concentrate his energies on a progress none the less rapid that it was not the progress of the Music Drama or the Latter-Day Programme Music. Let us sum up the problem (such as it is) of Dr. Joachim’s attitude to Wagner by stating once for all that those whose admiration for Wagner is inconsistent with a deep reverence for Dr. Joachim’s artistic aims and achievements are precisely as foolish as a man who professes a great insight into the highest forms of drama, while he sneers at the entire range of art covered by painting, sculpture and architecture.

Having brushed away this cobweb (which some people seem to take as quite a formidable obstacle), it is difficult to trump up anything else that one can regard as a limit to Dr. Joachim’s insight. True, I once heard an interesting young man charge him with being able to play “nothing but Bach, Beethoven and Brahms,” which at first seemed to me a compliment — though a very badly expressed one — and under that impression I elicited from him the admission that he had forgotten to mention Schumann, Schubert, Mendelssohn, the old Italians, Spohr and a few other miscellaneous writers, after which I began dimly to realise that the interesting young man had meant to make strictures on Dr. Joachim’s range of expression, while the interesting young man began dimly to realise that he had made a fool of himself. The reader will probably ask in wonder: “Why quote such foolish opinions? Are they not so insignificant that to notice them at all is like a confession of weakness?” It would be so if our object in writing and reading this article were to compliment and apologise for Dr. Joachim — but it is devoutly to be hoped that no musical person in the civilised world is so impudently stupid as to conceive any such idea. Our object is simply to bring before ourselves some dim notion of the actual differences between a great artist and the ordinary run of experts, amateurs, and Philistines, and for this purpose it is really important to meet the tomfooleries of “the man in the street,” with something more definite and more argumentative than the bare assertion : “You, an ordinary man, are talking nonsense about a great man.” The best compliment we can pay the great man is to shew that we differ from more foolish members of the crowd in our appreciation of his work — not merely in the orthodoxy of our catch-words.

The range of Dr. Joachim’s power as an interpreter is (when we give the matter a moment’s thought) obviously co-extensive with all that is called “classical” music together with the so-called “Romantic” schools of Germany, and the “neo-classical” work of Brahms — a range of art which we may challenge any actor or opera singer to represent in their respective spheres. And there is not one single thing within that vast range which Dr. Joachim does not make his own; nor one single point in which his sympathies are not in full touch with the most exhaustive musical scholarship. As it is grievously disappointing that the title of an article should contain the word “personality” while the article itself contains not one word of gossip, I beg leave to illustrate the last observation by certain details of Dr. Joachim’s intellectual and artistic feats as shewn casually in private. These details have been communicated to me by a friend in whose veracity I have absolute confidence, but whose name I, unfortunately, am not at liberty to divulge. I am told that on one occasion Brahms copied out an interesting movement from a very early manuscript symphony of Haydn and sent it to Dr. Joachim as being some thing he could not possibly know—only to find that Dr. Joachim had known it before him. Again, my friend informs me that on his asking Dr. Joachim whether Brahms’ B flat major concerto was not the only one on classical lines that contained a scherzo, Dr. Joachim replied : “Of course — oh, I forgot! I think there is one by Litolff.” Many other little anecdotes of this kind may be vouched for; trivial, you will say, in themselves, but so thoroughly exhausting the whole ground of instrumental and choral music, and pointing to such absolute accuracy and certainty that from them alone we might form a picture of wide and deep musical scholarship in its highest form.

To turn now to the more important factor of quick sympathetic insight. My friend mentioned above furnished me with another piece of gossip which, perhaps, may not at once strike the reader as being so astonishing as it really is. Not long ago Dr. Joachim was playing in private a manuscript violin sonata with its composer, an ambitious student who wrote a handwriting which was an object of scorn and wrath to all who tried to read it. Neither the obscurities of the manuscript nor those of the composition seemed to have the slightest effect on Dr. Joachim, who, according to the account the composer afterwards gave, brought out every nuance, written or unwritten, exactly as it had been in the composer’s mind at the time of writing, including minute felicities of interpretation felt while the work was being planned, but forgotten as soon as it was written. To complete the picture, it appears that Dr. Joachim began his criticism by saying that “of course one hearing was not enough for such a difficult work” — not in any sarcastic spirit, for that seems almost unknown and completely unnatural to him, but in simple good faith as a piece of scientific caution! In order to appreciate this story we must bear in mind that students’ compositions and other dull works are not, as is sometimes supposed, easier to interpret than great classics. On the contrary, dull and ambitious works are vastly more difficult than the most complex of classics, because the dull work is always vague, partly in intention and partly in execution, producing irrelevant complexities by methods at once inadequate and redundant, whereas the complexity of a great classic, though often far more alarming, is the logical outcome of many consistent and supremely simple and intelligible principles, and long before it is unravelled wins the sympathy of the interpreter and gives his activities the right direction. The intellectual feat just described is by far the greatest tour de force I have ever read or heard of any player; and if ever a time comes when names may be revealed my readers will find that it is one of the best authenticated.

Some people will remember another extraordinary feat of intellectual sympathy publicly performed by Dr. Joachim in London a good many years ago. He was playing a violin sonata (I believe I am correct in saying that it was a work he did not like) by an extremely successful composer — who was playing the pianoforte part himself. The extremely successful composer came to the most beautiful theme in his work, really a very happily turned phrase. He threw it off carelessly as one might say “a poor thing, sir, but mine own.” Dr. Joachim took it up and it sounded as it might to the imagination of its composer in the first thrill of creative impulse. Some people have argued that the composer showed a charming modesty in playing it superficially himself. He showed nothing of the kind. The man who does not take himself and his work seriously must be either very conceited or in the lowest depths of despair. When we accuse a man of “taking himself too seriously” we mean that he expects others to take him more seriously than he or they take the rest of mankind: and our inaccurate language sometimes saddles us with the awful responsibility of having caused clever young people to sink into permanent nincompoopery because they have taken our shallow advice seriously and ceased to take themselves so. If the modest artist ever says “a poor thing, sir, but mine own,” there is much weight in the “but.” “A poor thing, sir, to you: but half the world to me when I found it was mine.” The modesty lies in cheerfully assuming that half one’s own world is a drop in the ocean of a great man’s thoughts. The great man never fails to take everything as seriously as it can be taken, jokes included. That is to say, if it is seasonable for him to make a joke he will simply and straightforwardly make the best joke in the world, just as a good athlete will simply and straightforwardly play the best possible game. To hear and see Dr. Joachim over a Haydn quartet is a lesson which should drive the superciliousness and precosity out of the most hardened of prigs, old or young. Haydn’s numberless jokes and drolleries tumble out helter-skelter with the absolute spontaneity and grace one sees in a kitten running after its tail; while throughout the most light-hearted tomfoolery one is carried away by the grand spirit and life of Haydn’s immensely broad and terse melodic and structural organisation. There is no tone of patronising acknowledgment that “old Papa Haydn” is “wonderfully clever for the time in which he lived”; if one wants a parallel for such a hideously inartistic attitude, those who have the happiness of knowing what it means to be a good athlete may realise some sort of parallel by trying to imagine their resentment if their fellow-players played frivolously during an exciting match.

Dr. Joachim’s treatment of Haydn is altogether in line with his treatment of Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, and everything else that he has to do, from teaching to making a speech. While playing Haydn’s most extravagant frolics with precisely that simple thoroughness with which Haydn wrote them, it is no effort to Dr. Joachim to go with Haydn in his sudden plunges into the sublime and mysterious; nor is it an unexpected change for him to turn from the last note of the Haydn quartet to Beethoven’s quartet in A minor — one of the two or three most profound and mysteriously emotional utterances in all art. The epigrammatic and thoughtful genius of Schumann has influenced him with the influence of a personal friend, and would have influenced him hardly the less if, like the influence of Haydn and Beethoven, it had been merely that of works and not direct and mutual from man to man. The mutual influence between him and Brahms is now no less historic, and it is deeply thrilling to note that it has been the mutual influence of two composers. The subject of Dr. Joachim’s compositions is a large one, and I hazard the guess that its importance will grow as the century proceeds. At present we are too much occupied with the latest fashions of musical cleverness to appreciate the real originality and power of a scanty collection of works whose brilliance is not that of the clever young man, and whose intellectual difficulty is not that of the latest application of Wagnerian Leit-Motif to the symphony; but when time shews the difference between the clever and the great men of the present day, then the nobility of style and firmness of aim which characterize Dr. Joachim’s works will reveal their vitality and secure them their place among the works of the last classical period in musical history. Those who are curious for further details as to Dr. Joachim’s influence on Brahms cannot do better than read Herr Andreas Moser’s deeply interesting work “Joseph Joachim Ein Lebensbild” (Berlin, 1898), wherein will also be found an account of his relations with Wagner and Liszt, which cannot fail to inspire the most violent and one-sided enthusiasts to a deeper respect, or rather reverence, for both Dr. Joachim and Liszt. One word more, suggested by the above work, which was prepared for Dr. Joachim’s “Diamond Jubilee” in Berlin. We still have in its freshness the recollection of that little ceremony performed at the London Philharmonic, when Dr. Joachim was presented with a golden wreath and congratulatory speeches were made; and many felt compelled to regret that the inevitable references to Dr. Joachim’s increasing age were not tinged with something more of a note of triumph. Critics who detect a slight increase in frequency of slips of intonation which show that the great violinist is a man and not a machine, have been known to assign this increase (doubtless a fact, but not an important one) to “failing powers.” Such critics have absolutely no business to exist, and are mentioned here merely because they mistake a dignified silence for a respectful fear of their opinions. Dr. Joachim retains to the full his unsurpassable power of presenting great musical compositions as wholes, and preserving the vitality and purport of their every detail in the light of the vividly presented whole. His tone can be overpowered only by coarse playing on the part of others; it remains absolutely pure and clear in pianissimos so light that the ordinary player’s pianissimos sound elephantine in comparison; and in fortissimos there is neither strain nor thinness. It is absolutely impossible to detect any sign of obscurity or uncertainty in his execution of such monstrously difficult works as Bach’s C major solo violin sonata, or his own splendid Hungarian Concerto. And no one has ever dreamt of hinting that there is any diminution in that unrivalled intellectual vigour which he has used for more than sixty years in the service of Beethoven, Schumann, and Brahms. No note of sadness, then, in speaking of his age! Rather let us remind ourselves of the triumphant philosophy of Browning’s “Rabbi ben Ezra” and let the thought of Dr. Joachim’s age only make us long to have been born to “grow old along with him” — to have heard with our own ears his whole life-work in the art of music, and now to have reached with him that “best which is yet to be” —

“The last of life for which the first was made”

Tamino.

III

The generalities of the two former articles make it possible for us now to enter into more definite details as to the qualities that make a performance at once faithful, individual, and great; and I propose, accordingly, to attempt a very cursory description of a few scattered salient points in Dr. Joachim’s playing. To those who have read my former articles such points will, I hope, seem to arrange themselves into their places in the great whole I have attempted faintly to illustrate; while for those who have not read the former articles, these points may at least help to stimulate thought.

The keystone to Dr. Joachim’s interpretation is, as we have already been led to believe, his grasp and presentation of musical compositions as wholes. To illustrate this directly would necessitate an exhaustive aesthetic analysis of some complete composition; and such an analysis would cover more than twice the bulk of the present three articles before it was finished in sufficient detail for comparison with the main features of an “ideal” (or real) rendering of the work. I propose, instead, to take a few typical cases of the great player’s treatment of one of his main means of expression, showing how he appreciates the essential aesthetic principles it involves. After that I shall conclude with a description of Dr. Joachim’s playing of a difficult episode in Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.

Let us consider Rhythm. Everybody feels that rhythm must not be expressed stiffly and mechanically; but few except very great players know how to make their rhythm free without making it weak and vague. These are platitudes; but their weakness as such arises mainly from our taking for granted that we know exactly what we mean by “stiff and mechanical rhythm.” We usually take it to mean rhythm that is mathematically exact, or that fits in with the tick of a metronome. If we try a few experiments in the way of doing what so few people have the remotest notion of doing, viz., listening accurately to our own or another’s unfinished playing, we shall probably find that the rhythm which strikes us as “stiff” is really very inaccurate indeed. And a moment’s reflection ought to convince us that, however infallible a metronome may be as to the position of the beats to which it is set, it has absolutely no control over what happens between the beats. Practising with metronome may be very good for an instrumental student, if it is not regarded as relieving one of responsibility for listening to one’s own rhythm; but in nine cases out of ten it simply means that one sinks into a blissful feeling of industry, and a coincidence of every fourth note with a tick of the metronome. Meanwhile one is playing a scale like this (if the printer will kindly so space the notes that the imaginative reader may take the gaps and commas as representing the facts of the rhythm so played): —

Every group begins on the beat, but no group properly fills out the beat. If the reader will accept a dogmatic statement which time and space prevent me from supporting by logical evidence, I will sum up all I need to say on this point by saying that “stiff rhythm” is always smaller than its own main beats; — infinitesimally so, of course, or all “stiff” players would discover and correct it at once. The reader must not imagine that these and the following observations will enable every player with a feeble rhythm to become great and vigorous by learning to drag.

Take an ordinary “intelligent” musician, of the kind that thinks Mozart an interesting but superseded precursor of Beethoven, and make him play you the following theme from the Andante of Mozart’s C major sonata for four hands: —

In a tolerably good case it is just possible that all the beats may be equal to one another ; but it is far more likely that the third beat in the first bar will come too soon; and if the demisemiquavers in that beat do not arrive with some touch of haste after the dotted notes, and if they do not descend with a prosaic little click that should indicate a more rapid movement than the player’s own tempo warrants, and if the final turn does not sound a little like an irrelevant remark in six grace notes without rhythmic ictus and without connexion from the long note before them: if none of these petty slovenlinesses occur, why then either your player is a remarkable man and you wrong him in taking him for the ordinary intelligent musician, or at least he is a wide awake person who listens to his own playing. In any case I believe that few who have not habitually thought of rhythm in this way or listened systematically to their playing and practising, will fail to be struck by the unexpected largeness of the above theme if they play it at an almost too flowing Andante tempo (about  = 116) and carefully put not only the main beats into their places but also the demisemiquavers.

= 116) and carefully put not only the main beats into their places but also the demisemiquavers.

If “stiff rhythm” is smaller than its own beats, then true artistic rhythm must be at least equal to its own beats. But as true artistic rhythm is as rare as any other true art, it follows that to us, who are so much more accustomed to stiff rhythm, and therefore take it as normal, true artistic rhythm always seems unexpectedly large for its pace. Taking players of real rhythmic power, it is astonishing to notice how, when they follow Dr. Joachim’s reading of a work (as players of real greatness and personality may well submit to do), they are forced to play actually slower than he does in order to produce an analogous impression of breadth and detail. If they tried to play at his pace their expression would become breathless and coarse. Among those who do not play much it is firmly and widely believed that Dr. Joachim’s tempi are unusually slow; because few people are sufficiently cool during his playing to observe such prosaic facts as the contrast between the actual rapid pace, and the breadth and detail of expression. But those who have had the thrilling experience of accompanying him have testified that while he can play extraordinarily slowly without losing swing and coherence, his quicker tempi are really unusually fast. Obviously a lively movement gains immensely in directness and vigour of expression, if while played with this extraordinary breadth it is also really very rapid, so that its changes and climaxes surprise one, no less by their swift onrush than by their strength and dignity; and obviously the player who cannot attain the breadth without losing the rapidity must be far inferior to the greatest in those most essential qualities of vividness and thrill, — but surely it is equally obvious that a player so limited is immensely superior to the man who attains rapidity and brilliance at the cost of breadth.

This largeness of rhythm must be looked for in the interpretation of all classical music however small or light-hearted it may seem. The giving of full measure is a primary quality in all great art, both productive and reproductive, and in all great personality. The finale of Haydn’s quartet in E flat, Op. 64, No.6: —

both shows it and demands it in performance, and exposes the littleness of a little player’s personality as mercilessly as does the finale of Beethoven’s A minor quartet.

So far we have been assuming no more than if true artistic rhythm were mathematically exact. The question will be eagerly asked, “Where does it diverge from strict time?” From the above considerations it might at first seem as if true rhythm could differ from exact rhythm only in being larger than its main beats; but this is obviously an unsatisfactory answer, because if some part of the rhythm is to be larger the remainder must clearly be smaller, so that the distinction we have made so much of between true and stiff rhythm would become valueless or at all events extremely difficult.

One part of the probable solution is that here another rhythmic principle is involved, viz., accent. Where true rhythm is free it expresses in accent all that it obscures in proportion (or quantity, as a student of prosody would say), and vice versa. There is an enormous amount of accent in Dr. Joachim’s playing; but we are not too much aware of it because, as with the length of the smallest notes, so with the least accented notes, full measure is given. But the amount of accent that there is normally on the beats is a thing that few realise who have not either accompanied him or screwed themselves up (or, rather, down) to listen to him with a prosaic and statistical mind. The passage in the first movement of Brahms’ B flat string quartet beginning —

and ending —

is played by Dr. Joachim and his Berlin colleagues with the utmost smoothness and in an intense pianissimo; yet the accents, unimaginably delicate and unobtrusive as they are, are so strong that after all that rhythmic swing, there is no mistaking the fact that the tied notes at the end are on the sixth, and not the first beat of the bar. I have met with a friend who detected this from the Berlin quartet’s performance before he saw the score.

What with accent and breadth, we may say, as before, that true rhythm always expresses the main rhythmic facts, without slurring over the less salient features. For instance, if there is a cross accent, true rhythm will show that it is not an ordinary accent; the ordinary accent will be felt in some way, while the cross accent is unmistakeably overriding it. Or if there is a phrase the point of which lies in its being rhythmically and expressively broader than its surroundings, true rhythm may make it larger than the main beats of its context, without making the context sound perfunctory, and without anything resembling a change of tempo such as the composer could indicate by a verbal instruction.

Of course the danger always is that ordinary imitators will find out “how these things are done,” and reproduce them in a stiff and coarse travesty. Herr Wirth, in the Berlin quartet, plays a certain group in the second variation of the finale of Beethoven’s E flat quartet, Op.74, thus (if the printer and reader will again take spacing as a representation of those rhythmic subtleties that transcend notation)—

Every note is large, but the pause on the upper D is quite extraordinary in length; yet the passage does not, in Herr Wirth’s hands, suggest another rhythm than Beethoven’s. But just now every young viola player of average intelligence and superior attitude plays it “as they do in the Berlin quartet,”

And the effect is vulgar beyond words. The actual prosaic difference between it and Herr Wirth’s enormous swing and suspense is, that the vulgar imitation suggests a different and coarser group than Beethoven’s, and reels drunkenly over the least emphasized note of the group instead of giving it its place in the bar as a thing delayed but not curtailed. True rhythm is far too delicate a thing to be attained by imitation.

To take another point (though we have only touched on the outskirts of the subject of rhythm) — that of the portamento or slide from one note to another. A device so natural to the violin and the voice cannot be condemned off-hand as inartistic; but the great principle involved in its proper use is this, that it must not detract from either of the notes between which it is made. Dr. Joachim, like all violinists, will make a portamento in the following phrase in the recapitulation of the first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

but whereas the ordinary player will begin caterwauling down long before one can possibly take that highest note for a minim, the supremely great player will hold it for two good beats, and then swoop deliberately but swiftly down the great drop on to the equally large lower note. The mathematical result may be that that bar is a little larger than the normal; but that will be reconciled with the context by imperceptible gradation and swing.

Turning to more protracted freedoms of tempo we shall find the same principles at work. If the composer does not intend a movement to be broken into sections at different tempi, no increase of breadth or of swing or onrush will in Dr. Joachim’s hands sound as if it were a thing possible to measure by metronome, even though actual metronome measurement should, as a fact, show a difference of double tempo between the extremes. How this is done is beyond analysis; it is a subtle question of accent, probably — accent by which the feeling of rhythmic ictus is kept at the same level through all variations of breadth and flow: much as the Meiningen orchestra contrives to make Brahms’s Tragic Overture sound as in bars of two beats, though it is playing it no faster than the great choral theme of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony where the beats are unmistakably four.

Of nuance there is neither space nor other possibility of saying much. A large part of the ground is already covered by the great principle we have observed as to rhythm — the expression of broad and salient features without loss of accuracy and largeness in subordinate places — while much of the rest is contained in the obvious inferences to be drawn from the extraordinary definiteness and delicacy of Dr. Joachim’s accent, as illustrated by such passages as the one above quoted from Brahms. Obviously such feats of rhythmic expression imply the most amazing range and gradation of tone; and it is not thinkable that such gradation should not serve other noble purposes as well as rhythmic ones. However, to discuss these would lead us into endless detail, and I must pass on with one brief remark to a shorts ketch of one of Dr. Joachim’s best-known passages of interpretation (if one may be pardoned for hastily coining such an absurd phrase), by way of conclusion. The reader may find out most of what I would wish to say of nuance by reading the above remarks on rhythm once more, mutatis mutandis. I will only pause to observe that, like rhythm and everything else, nuance organises whole phrases and whole works, not merely one note after another. I have heard a violinist of excellent intelligence and culture give out the theme of the slow movement of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, thus—

Every note was pure in tone and thrilling in expression, but the deadly dulness of the result simply passed belief. (This error is worth special mention, as there is no precise parallel for it in the case of rhythm.) Nuance must cover large surfaces, as well as details, if it is to mean anything.

Let us fly off at a tangent from this point to our final illustration of the effect and purport of truly great playing. Let us first imagine that we have heard a performance of Beethoven’s violin concerto, in which the orchestra has played the opening tutti simply and straightforwardly, but the soloist has devoted his entire self to the delivery of every phrase singly in the most dignified imaginable way. Let us imagine that the soloist (whose name I do not intend to mention) manages this by playing obviously much slower than the orchestra, and that when he comes to the latter part of the development the orchestra has to subside almost to inaudibility and entirely to rhythmic stagnation while he delivers each phrase as beautifully as a single phrase can be delivered (one in particular will always remain in my mind as a living embodiment of true rhythm and nuance, as far as such truth can be found in isolated phrases)—

Yet the whole episode remains a mystery. What on earth have these beautiful pieces of non-thematic declamation to do with the rest of the movement, and why does the orchestra suddenly romp in with the opening theme fortissimo in the ordinary tempo of the tutti? The man dominates the orchestra, but he does not make us understand either himself or it.

Now let us hear Dr. Joachim’s interpretation. On his entry the rhythm becomes as much more free as the phrases become more declamatory; but still he is evidently not playing in a different tempo from the tutti. Page after page he takes the theme from the orchestra, and transfigures but never obscures it, and when we come to the wonderful declamatory episode at the end of the development, what do we hear? First, the horns with that all-pervading rhythm  with which the movement began. The violin, with its pathetic and entirely independent melody, rules the harmonic structure, while this rhythm persists, always clear, always recognisable as in something like the general tempo of the movement. The violin’s melody moves from G minor to E flat, and at once the full round tone of the horn gives place to the hollow, reedy moan of bassoons. The significant rhythm still persists. The violin’s declamation reads the tonic E flat as flattened supertonic of l) (the main key of the work), and at once on the dominant of that key solemn trumpets and drums take up the momentous rhythm, and continue it in a quiet, steady tread while the violin’s phrases (amongst them that quoted just above) become at once more flowing, shorter and tranquil.

with which the movement began. The violin, with its pathetic and entirely independent melody, rules the harmonic structure, while this rhythm persists, always clear, always recognisable as in something like the general tempo of the movement. The violin’s melody moves from G minor to E flat, and at once the full round tone of the horn gives place to the hollow, reedy moan of bassoons. The significant rhythm still persists. The violin’s declamation reads the tonic E flat as flattened supertonic of l) (the main key of the work), and at once on the dominant of that key solemn trumpets and drums take up the momentous rhythm, and continue it in a quiet, steady tread while the violin’s phrases (amongst them that quoted just above) become at once more flowing, shorter and tranquil.

Suddenly there is a feeling of life newly astir, the violin rises in a short passage of confident matter-of-fact activity— an almost instantaneous crescendo, and the opening tutti theme (so long anticipated by the  rhythm in horns, bassoons, trumpets, &c., and at the last moment, pizzicato hints on the strings)— the opening tutti theme bursts forth as simply and inevitably as the sun at day break. Who has dominated the orchestra most— Dr. Joachim or the other player described above? Dr. Joachim has not only dominated but permeated the orchestra from beginning to end. He has made all its doings his own, as the great man always absorbs and employs his environment. By the way in which he has played that wonderful independent declamation in the development, he has made us feel that he himself is in those horn-notes; at Joachim’s call the horn tone changes with the tonality to the more mysterious bassoon-tone; Joachim is playing those trumpets that breathe anticipation, such as Milton sings when—

rhythm in horns, bassoons, trumpets, &c., and at the last moment, pizzicato hints on the strings)— the opening tutti theme bursts forth as simply and inevitably as the sun at day break. Who has dominated the orchestra most— Dr. Joachim or the other player described above? Dr. Joachim has not only dominated but permeated the orchestra from beginning to end. He has made all its doings his own, as the great man always absorbs and employs his environment. By the way in which he has played that wonderful independent declamation in the development, he has made us feel that he himself is in those horn-notes; at Joachim’s call the horn tone changes with the tonality to the more mysterious bassoon-tone; Joachim is playing those trumpets that breathe anticipation, such as Milton sings when—

“—kings sate still with awful eye,

As if they surely knew their Sovran Lord was by.”

It is often said (with less truth in the case

of the greatest than one is apt to imagine)

that the art of the actor and the player perish

with the individual life. The world will not

let the compositions of Joachim die; but,

even without these, a man who has his share

of the Götterfunken, and is such a power in

others’ lives, might be content to be forgotten. The preservation of names is the only means by which the greatness of an age can formally acknowledge its debt to the greatness of the past; but that debt remains as real and tremendous a fact whether the names are preserved or not; and it is the fact, and not the name, for which the great men work.

TAMINO.

To the Editor of the “Musical Gazette.”

Dear Sir, — Much as I agree with your contributor, “Tamino,” I cannot say that he has been very lucky in his anecdotes of Dr. Joachim’s “musical scholarship.” I venture to send you the subjoined specimen as an addition to “Tamino’s” article, as I believe it may convey to some musical students that definite impression that “Tamino’s” anecdotes seem to me to lack.

In Bach’s A minor sonata for unaccompanied violin there is a difference of reading as to the second note: —

Some authorities read G sharp, which at first sight seems obviously right. But G natural really makes a much better sense as a step in a downward scale (A G F E D), the descend being disturbed into the upper octave by the limited downward compass of the violin.

I happened a few years ago to mention to Dr. Joachim that I had been looking at an arrangement by Bach himself of this sonata for Clavier, transposed to D minor, a little-known though interesting piece of work, then recently published or reprinted, and only known to me by the merest accident. I hardly had time to mention it before Dr. Joachim said, “And was the second note in the bass natural?” and then explained to me why he asked the question.

It may be said that this was a violin composition constantly on his repertoire; but how many actors are there, or how many have there ever been, who could show such an absolutely ready familiarity with varied readings in, say, “Hamlet”? It is the scholarly attitude of mind that is so significant in this case; and it would seem still more significant to one who could have observed the startling promptness of Dr. Joachim’s question. —

Yours truly, D. F. Tovey.

Like this:

Like Loading...

LONG, low, irregular room, the walls painted a dull green, the vaulted ceiling rudely frescoed with skies and flying birds. On either hand are ranged the little white tables, which one never sees except in a coffee-house; each surrounded by a circle of guests, each bearing an appropriate array of glasses and a match-box with an economic receptacle for cigar ends. The whole place is full of men: officers from the garrison, employes of commerce or the law, casual visitors on a voyage of discovery: there must be over a hundred in all, and the only woman among them is Madame, dark-haired, buxom, and affable, directing her noiseless army of waiters from the counter.

LONG, low, irregular room, the walls painted a dull green, the vaulted ceiling rudely frescoed with skies and flying birds. On either hand are ranged the little white tables, which one never sees except in a coffee-house; each surrounded by a circle of guests, each bearing an appropriate array of glasses and a match-box with an economic receptacle for cigar ends. The whole place is full of men: officers from the garrison, employes of commerce or the law, casual visitors on a voyage of discovery: there must be over a hundred in all, and the only woman among them is Madame, dark-haired, buxom, and affable, directing her noiseless army of waiters from the counter.