New-York Tribune, 7 May, 1899, Illustrated Supplement

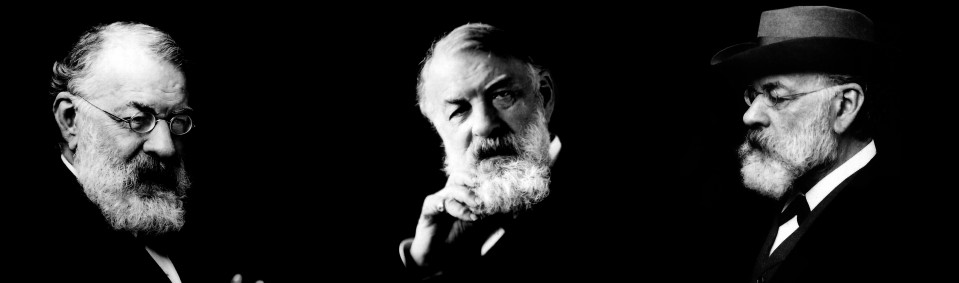

JOACHIM’S JUBILEE.

––––––––––

HOW THE SIXTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF

THE GREAT VIOLINIST’S FIRST AP-

PEARANCE WAS CELEBRATED

IN BERLIN.

Berlin, April 28.

The great hall of the Philharmonie was filled to overflowing on Saturday night, April 23, for the celebration of the jubilee of Joseph Joachim, who sixty years ago, a little boy, eight years old, made his first public appearance as a virtuoso in Budapest, and began the career which has made him the master violinist of Germany, and in the opinion of many of the whole world. Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and the entire “noble army” of musicians, who as cameo reliefs on the pale green wall keep watch over the splendid hall, looked down on one of the most brilliant assemblies of famous men and women ever gathered together in Berlin to honor a man great “by the grace of God.” Musicians, artists, men of letters and learning, high officers and Ministers of State, with countless orders gleaming on their breasts, crowded the parquet, the boxes and the gallery to bear witness to the esteem in which they held Germany’s “grand old man.”

He sat there among them in the centre of the hall, in his big chair of honor, decorated with gorgeous azaleas, smiling on them all, pleased as a child and modest as only a great man can be. Only a few minutes before every one of those thousands of men and women, from the highest dignitary to the humblest music student at the far corners of the hall, had risen and cheered at his entrance, while the trumpets of three of the finest regiments in Berlin sounded a fanfare of welcome. How simple he was, as he came in, accompanied by a few devoted men, stopping to shake hands with a friend in the box above him, or laying his hand affectionately on the shoulder of an old colleague as he passed him on his way down the aisle! The shouts of the people and the blare of the trumpets did not for one moment distract his attention from the familiar faces that beamed on him from all sides.

Indeed, they were all familiar faces. Robert von Mendelssohn, the banker and ‘cellist, descendant of the great Felix, and Joachim’s friend for many years, sat in the chair to his right. Across the passage to his left was the beloved old professor, Hermann Grimm, who had composed the prologue for the occasion, and coming toward him to welcome him was his friend and neighbor, Herr von Keudell. In the orchestra, every member of which was standing and waving his or her handkerchief, stood Wirth and Hausmann, Halir, and Moser and Markees, the two capable instigators and managers of the festival, and, besides these, old friends and pupils from all over the world, gray-haired men, middle-aged men, boys and girls, and no one could make noise enough. When the trumpets had ceased and the vast audience was seated, Fraulein Poppe, of the Royal Theatre, came to the front of the stage and recited the anniversary poem which Professor Grimm had written. It was a touching tribute, which grew in eloquence and feeling up to the last words, which were addressed to the orchestra, and as one exquisite mellow voice 144 stringed instruments responded with the opening strains of the overture to Weber’s “Euryanthe.” If ever an orchestra was inspired, that one was! No one who was not there can realize how perfectly the love and devotion to Joachim which every performer felt were breathed into that beautiful music. The audience sat spellbound. And no wonder, for such a collection of artists never played together before. Every city in Germany which could boast of a violin virtuoso sent him to play on this unique occasion, and not only Germany, but England, whose devotion to the great master is almost, if not quite, as great as that of his own country, sent the best two professors of the London Conservatory to represent her. Scattered among the older men were a few young ones, present pupils of Joachim, and about a dozen young girls in their light dresses, some of them with their hair still hanging in braids down their backs—German, English, American.

After the Joachim Variations, played by Petri, of Dresden, and after the overtures of Schumann and Mendelssohn, the “Genoveva” and “Midsummer Night’s Dream” and the Brahms Symphony in C Minor, there were three stars on the Programme. “What did they mean?” Every one looked at every one else and nobody knew, but a surprise was evidently in store. Then a note from some one on the stage was carried to Joachim, and at the same moment the whole orchestra rose and began to croon softly the first measures of the Beethoven Concerto. Then all understood and cheered and clapped, but the master himself was of a different mind. He could be seen expostulating and gesticulating and shaking his head and sitting down, only to get up again to expostulate further. But the orchestra never stopped; the soft music went on insistently—it would not be denied. The people behind the boxes, standing on tables and chairs, leaned forward, not to lose a sight or sound. “They’re bringing his violin,” the whisper ran through the excited crowd; and, sure enough, there came three girls, a deputation of his favorite pupils, down the aisle toward him, holding out his wonderful Stradivarius.

When he took it in his hand the music suddenly ceased, and every drum and horn and fiddle began to pound and toot and shriek in a most enthusiastic “Tusch.” When he had taken his stand, the noble old man turned to the audience in a modest, deprecating way and said: “I haven’t practiced for three days and my hands ache. I have clapped so hard. There are many men in this orchestra who can play this better than I can, but if you really wish me to, I’ll do my best.” A pinfall could have been heard when he began. Every one sat breathless, expectant, and no one was disappointed. If another man in the world could have played better, no one in the audience would have conceded as much, for to a German a false note by Joachim, the “violin king,” is more inspired than the most perfect note of any other violinist living.

When he was through and had returned to his comfortable chair, they made him come back again and again and bow and bow, and were not satisfied until he took the baton in his hand and himself conducted the last number on the programme, the Bach Concerto in G Major. It was written for three violins, three violas, three ‘cellos and basso continuo, but was played by sixty-six violins, the number of the other instruments being increased in proportion. The whole orchestra remained standing throughout in honor of the director, and he deserved it, for Bach, in Joachim’s hands, has beauties which the most stubborn Philistine must feel.

The public had been requested to depart immediately after the close of the concert, that the room might be cleared for the banquet that was to be held there in honor of the hero of the evening, so the rank and file went early, leaving the more fortunate to enjoy the speeches and reminiscences of bygone times.