By kind permission: University of Edinburgh Library Heritage Collections; Coll–1711/4/6 [English translation] and Coll–1711/4/8 [original German]

English translation, orthography, and spelling by Nina Joachim.

Der ursprüngliche deutsche Text folgt unten.

Reminiscences of Childhood

by

Amalie Joachim

(nee Schneeweiss)

Written for her Daughters and

Translated by her Grand-Daughter

Nina Joachim.

Christmas, 1957.

Early one Friday morning, at 9 o’clock, just as the bells in the little town of Marburg were ringing in honour of Our Saviour, I uttered my first cry. It must have been a loud and angry cry, for our family doctor, Dr. Jüttner — of whom I later became very fond — was taken aback at the sound and exclaimed: “Good God, I have never heard such a cry from a new-born baby.” My dear Mother was weak and could hardly smile at the cry; but, though her cheeks grew flushed and she became very feverish, she was very concerned when my screaming continued.

I screamed and screamed and refused everything. No soothing medicine helped — I just screamed! This screaming lasted for three days and then Dr. Jüttner laid down the law: “The child must leave the house. The mother is at death’s door and cannot recover so long as she hears the baby crying continually. The baby is unhappy and clearly does not like this world. She must go into the country”.

It was in the wonderful month of May and so I could be sent straight away to a peasant’s wife. This woman promised to feed both me and her own baby properly and my parents were free of me and at ease in their minds as I was in the safe keeping of some Wends. My mother was on the danger list and my father and grandfather were deeply anxious. The dear, beautiful wife and mother, centre-point of the whole house, was thought to be dying. My brother, who was ten years older than I, and my sister, were old enough to fear for Mother. My father, who worshipped his wife, and Grandpapa who, as their uncle, had brought up both Father and Mother, were both almost out of their minds with grief. It was only too understandable that I, poor wretch, was forgotten during this time, but when at last Mother opened her big blue eyes without fever, her first enquiry was for me. “Yes”, they said, “The child is being well looked after: she cried so incessantly that she was taken away”. Mother sent for me at once, but the report came that I could not be brought back as I slept continually — a sign of how good the country air was for me. When Mother was better and was allowed out, her first drive of course was to see me. I was asleep. Mother picked me up — Heavens! that was not natural sleep. Then the woman admitted that she had given me brandy so that my continual crying should stop. Of course I was immediately taken home — and, once I was free of the effects of brandy, began screaming again. At home they were in despair. At last Dr. Jüttner said, “Let the child scream. When she is bigger she will sing. The little creature needs to express herself aloud. You sing also, Frau Rätin, and there is music all day long in your house, until late at night. The child is only trying to outdo you!” Mother was delighted and cried: “May God grant that my little girl may one day become a good singer; I will do my bit towards it”. My fate was thus decided long before I was aware of it. Yes, if my dear Father had been able to do his bit towards it, I would perhaps have turned into a good singer, but – – -!

Arnoldstein, Carinthia, with the ruins of Schloss Arnoldstein on the left

Now I had better introduce Father, Mother and Grandpapa. Grandpapa! I have to shut my eyes and delve far back into my heart and memory if I want to see him. I remember very dimly a dear old face with something infinitely good and beautiful in it, viz. two eyes like stars, blue, large and shining, such as one hardly ever meets; snow-white hair with a black velvet cap, a kindly, almost toothless mouth, ever ready to tell us delicious stories. That is Grandpapa. He was the brother of Father’s father: Ignatius von Schneeweiss. He lived with a sister, Katharin, in Wolffsberg in Carinthia, not far from Schloss Arnoldstein, which was the entailed property of my real Grandfather. My father was born in the castle and was its legal heir. Grandpapa had a close friend, an officer called Lindes von Lindeman, who had come from Silesia. He had a sum of money and wanted to buy some property in Carinthia, but times in Austria were bad. Napoleon had smashed the world to ruins and thousands of lives were affected. Anyone who loved his country made sacrifice after sacrifice for it and my forebears brought of their best and laid it at the altar of their patriotism. The sacrifices were accepted — but what happened to our freedom and to our money — ? Both my grandfathers — for Lindes was the father of my mother — were impoverished. Lindes fell in a skirmish, and my grandfather Schneeweiss mortgaged his goods to the Church — in order to sacrifice even the little that remained of his property. The government later redeemed his property — that is to say, it took over the mortgage and Father received a small pension after the death of his father. Lindes left two children, my mother and her brother. The brother had been declared lost — it was said that he had followed the soldiers, seeking his father, when they had to march away. Mother’s mother was dead and Grandpapa took Mother into his house, as he was not destitute, but even after the state had gone bankrupt had sufficient means to live decently. He and his sister brought Mother up and betrothed her to the eldest son of Franz von Schneeweiss, who had meanwhile died and who was the former owner of Schloss Arnoldstein — which is beautiful to this very day. My father’s mother re-married and my father suffered a good deal at the hands of his stepfather. As soon as he was grown up, he left his stepfather’s house — that is, Schloss Arnoldstein, of which my grandmother’s husband was the trustee, and went to Klagenfurt, at Grandpapa’s expense, to study law. He was given a secure post at a comparatively early age in the little mountain town of Eisenerz. Soon after he brought his beautiful bride here, and — a blessing for their home — as dear Grandpapa’s sister had died in the meantime, he came to live with them too.

Ruins of Arnoldstein Castle, destroyed by fire 16 August 1883

Father did not stay there many years but was soon sent as an imperial official to Marburg in Styria. When my dear Mother later told us children stories of old times — how beautiful Arnoldstein was: (we had a drawing of it, which Mother had made); or how horrid Father’s stepfather was and how he let Father sleep under the stairs which led to the dungeon, where centuries earlier many a man had been kept prisoner; or when she told about the castles which the family had owned on the river Drau in the Wend country, which had been destroyed long since and which had the beautiful name of “Castle of the Dragons” (Drachenburg) and Draustein, and of the ancestral ghosts who still wandered about in the ruins — it was so gloriously creepy that we crouched close to Mother’s footstool and hardly dared to breathe. She also told stories out of her own life. Once when she was about eight years old, she came out of Grandpapa’s house and there was a little boy sitting on the stone seat in front of the house. He was not as old as she, had black curly hair, and stared at her wide-eyed. She shut the door quickly and cowered behind it, crying bitterly. Grandpapa’s sister, who was very pernickety and cross, called her and she had quickly to go and do some work. She would have dearly liked to bring the little boy in; but that was not to be thought of. It was evening before she could go to the door again. She looked out and saw the little boy sitting on the grass, crying. Mother asked: “What are you sitting here for?” He replied that his little sister must be in the house and he had walked for such a long time, for he came from Vienna, and the soldiers had been dead a long time and he was starving; Mother was so distressed that she fainted for a short time; meanwhile, other people came and looked at the little boy, who really was Carl Lindes, Mother’s brother. There were many stories like this one and they show what sorrow there was in our families; they went deep into our hearts and cast a shadow over our joy and made us long unceasingly for peaceful happiness. And yet — what a golden childhood was mine! In Father, who was such a serious and capable man and who had to rise to heavy responsibilities in his post, grew ever clearer the thought, which had been awakened in him by my first cry, that I must become a singer.

My older sister was delicate, and the mistake had been made of overpressing her with study. They planned to be wiser in my case and I was to be left free to sing. Well, that I did; I sat in the trees and competed with the birds. When I was four and a half years old, I was given a singing lesson by an old chorister. It was on the first of October, 1843. Father’s birthday was on October 4th and I was to sing a song from music. I knew the notes allright — my sister had introduced me to the mysteries of the black points — but what about the text?! Deeply ashamed, I had to admit that I could not read! Now I find it amusing that they were indignant at my not being able to read. It took me many weeks to teach my own children how to read, following well-known methods and a particularly bewildering system — and nobody had bothered about my learning to read! But the terrible fact was “Maltsche cannot read!” My sister had to come to the rescue. She promised that she would introduce me to the world of letters and would have taught me at any rate the relevant words by the birthday, which was to be celebrated by all the dignitaries of the town Marburg (to which my father had been moved). Three hard days followed. There were then 23 letters. How grateful I am to the illiteracy of those days which was content with one E and did not need five, as we unfortunate singers to-day have to use. We were also quite quickly finished with the G — our beloved dialect only knows one! Well, I sang the song proudly from the music and I can still see the fat Burgomaster before me. I had to sing directly to him and the wretched man laughed so that I was quite hurt and I do not think that my artistic achievement impressed him at all. However, the first step to singing in public had been taken — and it seemed that Father was pleased. Now I had to speak more German — our servants were Wends and we spoke Wendish better than German. Father also began to speak Italian to me and I was constantly told that this was the most important thing for a singer. In this way one or two years passed smoothly and there is only one event that I need mention. Some amateurs were studying the opera “Norma” for some purpose or other. (I heard this before my first performance — I was about three year old). I was allowed to go to the rehearsal. That was an experience! The impression that this rehearsal made on me was tremendous. For the first time Father’s wish that I should become a singer became my own desire. When I came home late that evening, I acted the great scene, in which Norma wishes to murder the children, so realistically, that my parents were quite overcome. I went on begging to go to the performance until permission was at last given. I spent the night almost in a state of delirium and began to sing out loud in my sleep. For months afterwards, I only sang “Norma”. My voice developed extremely quickly, and it became so high that I could easily sing the queen of the Night’s arias. There was a great deal of music in our house: Father played the violin and had a regular quartet, and we children were allowed to be present. My sister played the piano, my brother piano and cello, so that music in the house was well catered for. At that time, I got to know many quartets which I later heard at the hands of a master, the sounds coming back like dreams from my youth, but perfected and more beautiful. I had made a little corner for myself in Father’s room, where I could listen without being seen. If weariness overtook me, I fell asleep for a little — I was very young, and they played so late at night. My corner was behind the big stove by the two dogs; Mies and Bob were my best friends. They were mother and son — beautiful creatures — and they gladly allowed me to use them as pillows. Often very late at night the command came: “Maltschi is to sing”. Arias from Titus and Figaro, specially Mozart therefore, could always be turned on. I used to rub the sleep out of my eyes and start singing. Those were lovely times! The day was spent with the flowers and birds in the garden and the night with heavenly music. And so it went on until I was about eight years old. One day Mother said that she had to go to Carinthia, to Wolffsberg and Klagenfurt, about some property which she still had there. Grandpapa had now been dead a long time and the manager of the property which Mother had inherited suddenly seemed to her untrustworthy. Mother travelled by mail-coach, for there was no railway there then, and took me with her. I was too young to understand why she was so worried and wept so much, but I learned later that she had lost all her property through dishonest people It was hard. Father indeed had a good post, but his salary was not so very much and Mother’s property was big enough to be a considerable additional help to the household. We returned home a week later and found Father ill. He developed a strange illness and was a so-called “interesting case” for years. Doctors came from far and near to study Father’s case, but none was able to help. Then came the terrible year of ’48. My brother was a student in Vienna — we lived on the Hungarian border and we had friends who openly sided with the Hungarians. My father, as an imperial official, had to break with them because of his post. We all suffered under the billeting of the Croat troops, who were terribly rough and behaved as though they were in enemy country. When the Hungarians revolted from the Austrian army, there was a skirmish near our house, which was a little outside the town. Though we were forbidden to do so, we looked out of the gate and I saw what I will never forget as long as I live. Wretched human beings wounded by gunshot. Oh God! they were healed only to be executed!

All this time my brother was in Vienna and there was no news from him for months. One day we got such bad news from Vienna through a private channel that my Mother could not endure it any longer but went to my Father’s office in the hope of hearing something definite. My sister was at school, the maid had gone out to pick up any news she could, so I was alone in the house. I latched the door and was just about to lock it when I heard heavy steps coming from the stairs to the landing — I fled to the kitchen, and got into the wood store under the stove. From there I could see a ragged figure come in and go to Mother’s room. My heart was thumping and I did not know whether I should stay where I was, scream or run away; but of course I did the most stupid thing of all and went into Mother’s room myself. A pale, bleeding figure was lying on the sofa — it was my brother. He lay ther unconscious, starving, wounded, in a tattered Hungarian tunic. Thinking that wine was good in all emergencies, I poured some into his mouth. He recovered consciousness and at the same moment my parents rushed in. They had heard that a ragged man had entered the house and had immediately thought that it was my brother. My brother had been saved from prison and indeed from death by a miracle, that is to say, by a miracle brought about by a courageous comrade. A difficult time followed for us all. My brother, who had qualified in law, could not enter the service of the state, as he had taken part in the troubles in Vienna. He stayed. No-one had the courage to employ him. In the little country town everything was known by everyone. The only way to make people forget that Franz (my brother), had compromised himself politically was for him to join the army. This was the advice given to Father when he — himself a sick and broken man — went to Graz to find a post for his son. Father heard also that a complete revolution of the judicial system was imminent and that he himself would probably be moved from Marburg. So the future was very uncertain. Father, in constant pain, feared that he would be made to retire — which was all the more likely because, as some friends informed him, he was blamed for the fact that his son had taken part in the students’ fights. This last fact greatly influenced my brother’s final decision and at last he joined the army. He joined our Styrian regiment as a regimental cadet, which about corresponded to our one-year conscripts — and was soon sent to Leghorn. This was a great blow for us all: Order had been restored no better in Italy than in Hungary and new battles were daily expected. My brother was to experience something worse than opposing in battle those whose views he shared. The enemy was hunted down in a secret fashion. Almost every day the flower of Italian and Hungarian manhood in the freshness of their youth were delivered to the barracks and every few days our troops were ordered to shoot them down in masses in the courtyard. My brother suffered so that he stood in danger of losing his reason. My father also had to go through a hard time. The judicial system was altered. With his years of service, he ought to have been given an important post in some big city, but he was in fact sent to a subordinate post at the little town of Bruck and der Mur in Upper Austria. This was the death blow for our dear Father. We left our beloved, sunny Marburg in the autumn of 1850 and went to Bruck, which was situated in the heart of the mountains, cold and sunless. After a bad winter, in which we suffered terribly, Father died in April. The move and Father’s last illness ate up the last remnants of our property and Mother was left helpless and without means with two girls. We still were to make one terrible discovery. We had heard nothing for months from Franz in Italy. When Father’s eyes were closed for ever, Mother found in his desk one of her letters to Franz, on the envelope of which was written: “Addressee deserted a fortnight ago and not yet recaptured”. In this letter Mother had implored Franz to carry on and to do his duty faithfully and she had told him openly about the desperate state of Father’s health. The letter came back to Father’s office and it had been sent to his home with various official papers. He had read it and concealed it from Mother, hoping no doubt to give it to her when he was in better health and she more hopeful. So Mother had lost both husband and son and this prostrated her. She became seriously ill and I, who was twelve, stood by her bed in despair. I can still see every chair, every picture in that room in which she was ill. Father lay dead in his own room and people surged to and fro and prayed aloud, and we could only stand dumbly there with dry, hot eyes. Her duty to us gave Mother the strength to pull herself together sufficiently to do what was necessary. Father was hardly buried before everything that we could dispense with had been sold and Mother moved to Graz with us, where she had old friends and acquaintances. Her brother still lived there and she hoped that she would be able to bring us up more easily there. Oh God, what disappointments she had to endure! Those old friends, who were poor, knew her and were at least friendly — but those who were well off, quickly withdrew or even would not know us at all when we approached them. A terrible time followed; there was no help anywhere. Mother had to wait a whole year before she received her little pension. The only thing to do was to work. Mother had magic in her hands and could do the finest knitting. She knitted the finest christening bonnets and jackets for small children, which looked like spiders’ webs, and my sister and I embroidered them. There was a big shop in Graz for such goods and the proprietor ordered and bought from us. But what a labour it was — and how little money! My sister was delicate and was supposed to practice the piano for several hours daily, as Mother thought she ought to become a pianist. But what with the embroidery and insufficient food she grew steadily weaker in health. Mother’s despair grew daily as did the pallor and weakness of the delicate, beautiful, fairy-like girl. I was healthy and strong and could stay up and work for nights on end. But Mother also worried about my voice. I could not be taught, for where was a teacher who would teach me for nothing? Mother put my name down for the city conservatorium. That was all very pleasant and I always went to the classes, but I could not learn very much there. The conductor made me sing to him. “Yes”, he said, “That is allright. Come to the auditions the day after to-morrow and sing the Aria, “Und ob die Wolke” from the “Freischütz”. The burgomaster is coming and a big audience. If you do it well, something will come of it”. I was delighted. I could not imagine what would come of it — but it was wonderful to be allowed to perform; I had not sung in public since Marburg. I sang in the parish church in Bruck, but apart from that I only made music with my sister. I had long known the parts of Agathe, Annchen in the “Freischütz”, Gabriele in “Nachtlager”, Pamina, by heart — and now at long last to sing in public — ! But Good Heavens! A concert — dresses! My mourning dress was at least new and I could appear in it; but my boots! They looked as though they had been made to last for ever: they had thick soles and were of strong calf. I did not want to talk to Mother about it but I took Minna, my sister, into my confidence and asked her whether it would be suitable to come to the stage in front of the burgomaster in my boots — my dress after all was short. Minna knew what to do. The boots must be cleaned so that they shone well. Yes, that helped. They shone like anything, for I polished them for at least an hour, and if they weren’t looked at too closely, they might have been taken for patent leather. And so I walked on air down the long road and across the glacis into the town, into the council hall, and arrived of course a couple of hours too early. I felt quite sick, what with the wait, and the heat, and the excitement! At last it started. The burgomaster came; he was exactly like his opposite number at Saardam. He was fat and shining and understood just as much about singing as did my sham patent leather boots. But when I had sung and then amid great applause jumped down, very embarrassed, from the stage (when I was happy, I never could walk but always jumped — a habit which I kept for a long time) he beckoned me to him, stroked my head and gave me a velvet bag. He told me always to be good and well-behaved and released me graciously. I ran over to Mother, who was sitting next to the other proud mothers, and when we opened the bag, there were four ducats inside in the velvet! That was wonderful — my singing — four ducats! My delight was enormous and a glimpse of sunshine after such long, sad years.

I remained as a free pupil at the conservatorium but I did not really learn very much there. But there was someone in the town whom I dearly loved, Julie von Frank, who took a great interest in me and worked with me. She was very musical and had heard a great deal of music. I began to study parts with her. I did not find learning by heart at all difficult and I soon had quite a good repertoire. But I was still too young and looked too childish to go on the stage. The director of the theatre at Graz tested me, but the conductor, who would not believe that I was only just thirteen, thought that, though my voice was strong, I must be consumptive as I looked so delicate. When I was fourteen, I sang to a theatre agent from Vienna. He engaged me at once from the following Autumn for the theatre in Troppau. So my great desire was fulfilled and there was the prospect of gradual financial improvement.

But what distress and sorrow lay behind us! I will only recount one small episode from our life there — much that is similar had best remain untold. It was nearly Christmas time and we had a good many orders for little christening bonnets and jackets. We worked day and night, but my sister fell ill and could do nothing. The work had to be delivered before Christmas; Christmas Eve came and the orders were only completed late. My sister was in bed. Mother did not want to leave her and, though she did not like letting me go out alone to deliver the orders, she had to do so this time. So I was sent off with a little basket full of our work and was told to buy some meat when I had been given the money, so that my sister could have a good supper. Mother and I were only going to eat eggs, for as strict Catholics we had to fast. Fast! oh God — for days we had not had a farthing in the house and had already fasted for a long time! So I hurried into the town, for it was late and I was afraid of going over the lonely glacis. I could already see some brightly lit windows and happy people inside. Anxiety that I might come too late and not be able to get rid of the work and fear at being almost alone in the streets, lent me wings. At last I reached the house. All the windows were lit up and I flew up the steps. At last a maid came: “What, have you come? Now? Good Heavens, nobody thinks of business now. Well, I will tell Madam that you have brought the work”. She disappeared and returned with the message that I should leave the work there and call again after the Christmas days. I asked for an advance of money, as we needed it. It was hard for me to say the words and they fell like drops of ice from my lips. They did not warm the maid either, for she murmured something about a big party and that she could not disturb them; then she took the basket and shut the door. I went slowly home, no longer afraid of the walk. I stood in front of our door for a long time and thought of the illuminated windows and the gay people and could not find courage to go up. At last I heard Mother looking out for me from the window. I went upstairs to a room which had meanwhile become cold and told my story. No-one said anything. After some time a gentle sigh came from my sister’s lips: “Father, how lucky you are”. We went to bed quietly — I slipped into my sister’s bed to warm her and lay still, but I could not sleep for I heard Mother quietly praying. What must my Mother have felt? She was so beautiful, so gifted — she sang, she painted, she drew, she had been fêted as a great beauty and a young woman of brilliant intellect; later she was worshipped by her husband; and now she had not even got bread for her children; she could not meet the common needs of education and care for those whom she so loved and who deeply loved and revered her. My poor Mother! — I believe certainly that such experiences make people mature but they can also make them bitter. My beautiful and gifted sister shut herself more and more away from people and from the world.

Still we also had our joys and I will be just and recount these also. A family, former acquaintances of my parents, lived opposite us. The children were musical; one daughter sang and took singing lessons from me, although she was considerably older than I was. I did not earn much from this — still it was about two Florins a month. We used often to play in the big garden and in the winter we danced. Dancing was almost as lovely as singing! Grand plans were made. The dear people knew that I wanted to go on the stage and so they set up a small stage for us children and we acted some plays by Kotzebue, who was then in fashion. That was glorious! I always took man’s parts” once Fritz Hurlebusch and once the “Posthalter of Treuenbritzen”. But I was also producer, mistress of the wardrobe, prompter and stage-manager. I was happy to be allowed to act and to get some practice. There was much work in 1853. I was just fourteen years old. I had got a contract through an agent for the best juvenile parts at Troppau and a salary of 30 Florins a month. It was not much but we had to live on it. The hope was that I would get on and in time would earn more. Sometime or other I would receive a larger salary — so, courage! Father’s wish was that I should become a singer — for Mother a last wish to be piously fulfilled and for me a most ardent desire. I had to have dresses for the theatre and there was no money for them. There was nothing for it but to buy material and to make my costumes as best we could and instead of paying in cash we had to make Mother’s pension over to the shop for a whole year. I had to get to Troppau in September. All our furniture was sold to pay for the journey and now nothing was left to remind us of our former comfort. My poor Mother! She seems a heroine and a martyr to me now! We travelled to Troppau in the middle of September via Vienna and so I saw the imperial city for the first time. My sister had once before been in Vienna, when applying to the Emperor for an educational or orphans grant for us. We were not given anything as we were only two children and Mother was expected to keep us in luxury on her yearly pension of 226 Florins. Each year has 365 days — but it would have been too sumptuous if the widow of a state official, who had done his duty for more than twenty-five years and had sacrificed his strength in his job, were to need more than 50 Kreutzer daily for herself and her two children. That was Austria! After two days in Vienna we at last arrived in Troppau.

I looked forward to my new profession joyfully and serenely. I was so young and believed that my happiness in being at last able to sing in public and to make my appearance on the stage would carry me over every difficulty. With the easy confidence of youth I appeared before the audiences — indeed my youth soon won the public. The producer, Frau Rosner, who had been an excellent singer, had rented the theatre and ruled with a rod of iron. She was small and fat, with a wonderfully animated expression. She gazed at me with horrified eyes when I was presented to her. “That child? Yes, the agent had said she was young — but so young? I am curious to hear what sort of a squeak she will produce. She certainly cannot sing the great parts!” That did not sound friendly but it did not take away my courage. There was already someone ther for the juvenile parts and I was to take a very small rôle at first: that of the queen in “The Puritans”. There were only a few bars to sing but I had to walk “regally” across the stage. Well — I succeeded. I came on at the right time, sang and acted suitably, and the producer smiled! My second part was the queen in “Die Zigeunerin” (The Gypsy) by Balfe — an opera which was very popular at that time. In this there was more to sing and a great deal of acting. It came off and the producer said “The girl has talent — she is better than my other youthful acquisitions. We shall see”. Three days later she sent to ask me if I could sing Adalgisa the next day. I called to the theatre attendant: “Yes, of course — if need be without rehearsal”. This also went well and after that I was given all kinds of parts — soubrette, juvenile parts, dramatic parts, etc. My voice was then very high and I sang everything: Annchen in the “Freischütz”, Julia in “Romeo”, Gabriele in “Nachtlager”, Zerline in “Fra Diavolo”. In between I sang in operettas and even took parts in plays as I could speak tolerably well. I was exceedingly happy. The public was always nice to me — my goodness, what a child I was! — and I could learn such a lot, especially in acting. There was still a good deal to worry me at home. My small wardrobe was insufficient and many new things had to be made. We made everything ourselves. My mother and sister bought everything and I could not do much besides my continual practising. I certainly had to endure some hard times. I was healthy but all the ssame fairly delicate. The great parts were tiring, and our food was insufficient. The winter was very cold and the theatre horribly draughty. I often suffered greatly from the cold. One day we were giving “Die Weisse Frau” and I was singing Jenny. Snow fell on my shoulders in the first Act. The stove in the dressing room smoked badly and so there was no heating. After the opera Mother came to the dressing room and found me unconscious with stiff limbs and half undressed. She rubbed me and at last I was sufficiently restored to be taken to our home, which was near. I was really ill for a few days, but recovered and was none the worse.

In Troppau the theatre was open during the winter only and we had to look for an engagement for a year. We succeeded in finding this and I was appointed for one year at a salary of 600 Florins at Hermannstadt in Siebenbürgen. That was certainly a slight improvement but it was a long journey. In those days one had to go from Pest, where the railway ended, by mailcoach to Hermannstadt — a journey of five or six days, that is, day and night. The only thing to do was once more to hand over Mother’s whole year’s pension as a guarantee. The business man in Graz advanced us the money but required Mother to take out an insurance so that he would be covered in the event of her death. This involved us in further outlay. We came to the difficult decision to part from my sister. She was to go for the time being as household help to a friend of Mother’s, who had several children, until we had sufficient means to get her to follow us. To leave my delicate sister behind was indeed a hard decision! However, her health had somewhat improved, and she was more cheerful. The life of the stage, which she could enjoy vicariously through me, enlivened her. She could also spend more time at her piano and she sometimes played at charity concerts. The fact that she was always very successful on these occasions made her both more relaxed and more hopeful. Indeed, how could it have been otherwise? She was one of the most beautiful girls imaginable. She was a delicate, ethereal creature with a mass of golden hair and most beautiful blue eyes. She was tall and slender and extremely attractive. Mother used to tell us how, once when she was very small and they were out walking, the carriage of the Emperor Franz’s last wife passed them. The Empress nodded to my Mother, who was curtseying, and saw my sister. She commanded her carriage to stop and had the child handed to her. “You are both a fortunate and an unfortunate Mother! It is great happiness to possess such a beautiful child; but the child cannot live, for only angels are so beautiful. To love this child would be an unbearable grief”. Mother bowed and answered: “Your Majesty, children are only lent to us so that we can prepare them for Heaven”. The Empress gave her her hand and said: “May God protect you and leave you your treasure for a long time”. The pious wish of the Empress was fulfilled. My Mother did not live to see the tragic fading of the beautiful child; but my sister joined the angels too soon, much too soon, fulfilling the words of the Empress. We travelled to Vienna after Easter 1854. Once again I sang to the agent. After a stay of three days there, my sister Minna went to Graz and Mother and I went to Hermannstadt.

It was an extremely interesting journey. We went by train from Vienna to Pest and had to stay several hours in Pest as there were great difficulties over our passports. There we heard that we could travel more cheaply, though rather longer, with a privately owned coach, which only travelled by day, putting up at night in good, simple inns. Mother found this preferable and we made this arrangement. The owner was a jolly, amusing man and seemed very reliable. He promised me that I should hear some genuine gypsy music and see some true Steppe-dwellers and eat the real goulasch, which they cooked in great pots in the open. So we drove happily off with him and he kept his promise. We started every day at about 6 o’clock and reached an unpretentious inn or farm at about mid-day, where a simple but good meal awaited us, and towards evening we arrived at a village where we were to spend the night, and usually found decent beds. When one considers that there were two carriages like omnibuses — that is to say, about 18 or 20 people, one can only marvel at the organisation. The arrangements were exact, punctual and extremely clean, which is not always so in Hungary. One evening — it was a Sunday — we arrived at an inn from which we heard music as we drew up. The guest room was thick with smoke and full of black-bearded gypsies, smoking and drinking. We needed food and so we sat down in the room. Some gypsies were standing, others were sitting on a great barrel; they were singing and playing. The tunes sounded wonderful on the hard violins. The cymbal [cimbalom] player played excellently and when he noticed that his playing interested me, he began to improvise more beautifully. Besides Mother and me, there were only the landlady, a servant girl and a woman who, with her two children, was our travelling companion. The men wanted to dance, and as the landlady and the maid had to serve, there was no partner available except — me! Along came a young man shyly and respectfully and asked if “Gnädiges Freilein” would dance a Czardas. Mother indicated at once that I should accept and so off I went, and many dances followed that first one. At first I was a bit frightened and so I believe was my dear Mother; but these men and young fellows, who had certainly never danced with a “Fräulein” before, behaved like cavaliers in spite of the wildness of the dances and always escorted me back to Mother with knightly courtesy. I never experienced another night like that! There was no house in sight — only the wide plain stretching as far as the eye could see — and there were we women among these fierce, strange natives of the steppe — and the wild music — and outside moonshine and the peaceful loneliness. My heart swelled, I was only a girl fifteen years old; I slipped outside and began to sing — probably improvising after having heard the cymbals? Suddenly a shout of “Bravo” nearby. Everybody had come out without my having heard them: they burst out in acclamation and carried me triumphantly back into the inn. The next morning we started rather later than usual and all was quiet — the wild lads had disappeared like a dream. I asked our driver where everybody had disappeared to. “Who knows?” said he, “the poor fellows only gather together secretly. You know how things are with us. Many of those young men are honest peasants (Czikos) enough but some are different. There is martial law in every village and the authorities can shoot them if they are found. They are poor devils who do best to avoid the light of day”. We were rather horrified to think that the hand which held mine when we were dancing was perhaps stained with blood. But in those days in Hungary, if the landowner was stern, stealing a goose was punished with death. The lad who had stolen a goose had indeed no alternative but to become a bandit.

We travelled for nine days before we at last arrived in Hermannstadt one evening. We went straight to the theatre, where the play was not yet finished, to enquire about our room which had been taken in advance for us. “Fiesco” was being given and “Julie” introduced herself at once as Frau Kreibig, the producer’s wife. She welcomed me very kindly, and said she knew that I was still very young but did my work well and that she was very much looking forward to hearing me. I had practised many parts which I hoped to be able to sing — but of course not the one in which I was to appear: “Leonore” in “Stradella”. But I had four days. Another opera could not be given straight away because of re-casting. I had never heard this particular opera. There was a rehearsal the next day. The conductor was not very pleasant but he was competent. I had really mastered my part and it was a success. The producer himself was in Vienna and only returned later. My second part was “The Gypsy”. I had sung a subordinate part in Troppau and had learned the main part at the same time; I was quite confident in it and happy and was again extremely successful. I had to sing about twice a week and I also undertook parts in plays and operettes so that I might become really proficient. It now seems amusing to me that I chose “The Marriage of Figaro” as my benefit performance and sang Susanna. My voice was so high and light that I liked singing high coloratura best. I sang Pamina in the “Magic Flute”, Mirrha in the “Unterbrochenen Opferfest“ by Winter, and all the high soubrette parts. We made some close friends in Hermannstadt, who stood by Mother loyally. We lived simply and we tried to manage with what I earned, but having to acquire the necessary dresses for the theatre caused us real privation. At that time I learned tailoring secretly, so as to be able to make my dresses more easily. But my fellow-actors and the audience were not to know this. Agents came from Bucharest who tried to persuade Mother to send me to the theatre there — but Mother would not hear of it. I received anonymous letters promising me the earth if I would leave Mother and go to Bucharest. I gave these letters — as indeed I gave all letters I received — to Mother. For some months all went well and we hoped to stay in Hermannstadt for several years, to let my sister come to us, and through saving at last to improve our financial position. But a great misfortune befell us: one fine day the producer disappeared. The business was not going well and he had a large family — enough said; he disappeared and left us all in the lurch in Hermannstadt, without having paid our last month’s salaries. Most of us were in great difficulties. It was indeed hard! This was at the end of July. The theatres only opened at the end of September, so what were we to do? How were we to live for three months? Salaries were not paid before the first of November. Should we stay in Hermannstadt or try to get away? We did not know what to do. The shock made me ill and I ran a high temperature. My poor Mother was once again overwhelmed by trouble. I recovered quite quickly but we were so unhappy that we might have done anything. However, we never thought of Bucharest! An agent in Vienna sent me an engagement at Ansbach in Bavaria. The theatre had no reputation, the salary was small and it was a long journey. We insisted that at least my fare should be paid and the producer finally agreed. But what were we to do till then? Our producer had made an arrangement with a man whose name I cannot remember but who always took the part of a monkey — entire plays were written for him with the monkey as the main character. He had not heard about the collapse of the theatre and came to Hermannstadt. This was a ray of hope! A few colleagues arranged with the monkey-man that we should act with him. He agreed and we acted for several weeks. We had to act whatever part he gave us. I took many small parts but also one big one — that of a deaf and dumb boy who had become dumb through shock when a child, wandered round with the monkey until he was a young man and finally regained his power of speech by the shock of finding his parents and his home. Studying this part interested me so much that I forgot our sad position. I won such favour with the monkey-man that he wanted to take me with him for this and similar parts. Thank God that was impossible because of my Ansbach engagement! I do not remember what Mother did at that time, and how she got the money to travel with me in September to Vienna. I only remember that she said she had to promise to pay high interest rates and that we were deeply in debt. So after those few months we left for Vienna by mail-coach, which travelled day and night but was supposed to reach Pest in five days. Our mood was different now than on the outward journey. The overloaded coach seemed to crawl over the steppe. The guard and driver were armed with pistols: they were afraid of meeting my dancers. We had adventures — but most unromantic ones. The main question was whether the driver was a drunk or not. Sometimes he drove off when all the passengers were still eating their supper in the inn and we had to run after him. The guard then beat the driver and sometimes he retaliated. It was all very unpleasant. Two nights before we should have reached Pest, our coach went up a pathless hill at about midnight, swayed to and fro and fell down a slope. There was a woman with young children there too. The first coach was far in front and went merrily on — and we lay there; I did not know how to get up and out. Mother was strangely quiet but the woman cried as loudly as the children. At last the guard came limping up, bringing a lantern, and helped me and the others out — but Mother lay underneath us all, covered with blood and unconscious. It took a long time before she came to. The coach was righted, the luggage tied on and we were slowly driven back to the last inn. It seemed an eternity to me before the postmaster was knocked up. Blood streamed down Mother’s face the whole time and I could not touch her as there were splinters in her head, as I discovered by gently feeling her. She was put to bed at once in the inn and the innkeeper, who was presumably used to such occurrences, got the big splinters out himself and told me that I was to cut her hair back at the sides as soon as it was daylight and get out some more splinters. Then he left us and I spent an unhappy night. It was dreadful to see my dear Mother suffer so, after she had undertaken this terrible journey for my sake and undergone such privations. Mother kept on fainting and there was I, all alone with her in a strange house. That night I vowed to dedicate everything, all my love and care, to her and not to weaken or go back on this until I had repaid her. She should be able to say with pride: “This is my child and through my faithfulness I have made her what she is”! How rarely have we the power to carry out our good intentions. My poor Mother still had to go through difficult times and I could not recompense her for her devotion. How many thousands of times I was later to wish, when she was long dead, to have her back just for a moment, so as to repay her, and how often I longed to lean on her faithful breast and weep and seek and find comfort; a Mother’s heart is a sacred place which can heal our wounds and comfort us in our despair. No one should undervalue this!

Next morning things seemed a little better. Mother was hurt but only externally, on her head; she was weak from shock, but we hoped she would be restored after a few days’ rest. And so it turned out. We had to stay a week in the little village and then the postmaster himself took us to the station at Pest. Nothing happened to me as a result of the accident except that I had to carry a swollen, blue nose around with me for several days.

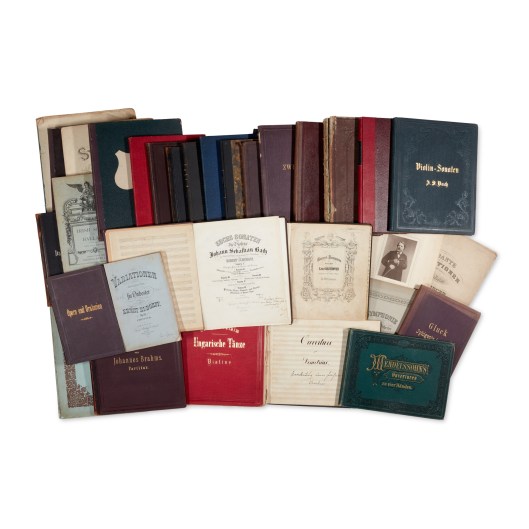

We expected my sister in Vienna as she was to go to Ansbach with us. We had written to her during our enforced stay in Hungary that I would arrive later because of an accident. Our distress can be imagined when we at last arrived in Vienna and found that my contract had been cancelled because I had not arrived at the proper time! Fresh worries! Mother took her courage in both hands and went to Alois Ander[1], a celebrated “Kammersänger”, at that time at the height of his fame. He listened to Mother and got her to take me to him at once and made me sing to him. Mother fetched me — he smiled at me in a friendly way and said: “Hm, you are young enough and if your voice is half as beautiful as – – – but one must not make such a young girl vain. Sing away!” He began to play the page’s aria in Figaro and after I had sung four bars, he said “Come with me to Herr Cornet,[2] the producer, and don’t be afraid however much he shouts at you! He is a hefty Tyrolese and always shouts — but it doesn’t mean much”. If I had known how the “hefty Tyrolese” would hurt me later, I would not have gone with Ander! He took me to the Kärntnertor theatre and, terrified, I entered the great rehearsal room. A frightening half-hour passed before the awe-inspiring producer came in, with several gentlemen. He was a small man, ugly and deformed but with glowing black eyes; in a powerful voice he asked for Susanna’s aria. The conductor, Herr Esser, was with him and played the accompaniment. “Well, your voice is good — but you have not learnt much. But one can hear that you are musical”. “And I am young enough to learn if I am given a chance”; the words slipped out of my mouth. “Yes, you are called ‘Fresh as snow’ and ‘fresh’ you certainly are! I engage you for a trial period of three months at a salary of 30 Florins. You must come daily to the theatre to study a part that you have not yet sung. I will give you a week — then you will rehearse with the stage-manager and then you will perform; on that depends whether you will be engaged for longer”.

Kärntnertortheater, Vienna

I was delighted and Mother and I went to our inn where Minna was eagerly waiting for news. We were overjoyed! Vienna! The Kärntnertor theatre! It is difficult to realize how important this famous imperial court theatre appeared to a little singer. How magnificent the enormous building was for those times! The rehearsal room alone was bigger, it seemed to me, than the whole Hermannstadt theatre.

We looked for a small flat and found one on the fourth floor in a street near the theatre. We seemed terribly grand to ourselves when we thought of our poor little room in Hermannstadt! The next day I went to practise the “new part” in the theatre. A horrid, small, fat, greasy creature came to practise with me. He looked down his nose at me: “Well, we shan’t of course be musical; I know it, it will be tiresome once again!” At last I learned that I was to practise Fatima in “Oberon”. It was a small part but not an easy one, as she has to speak a lot and in Vienna the great comic scene, which demands a skilled actress, was included. Fräulein Wildauer[3] had sung the part last — an excellent singer of the Burgtheatre. My rehearser told me all this, to cheer me up, before we began. I sight-read well, which he admitted with a sour-sweet smile. I rehearsed for another two days. The producer, Herr Cornet, came in and demanded that I should do the first duet with him — he wanted to mark the recitatives. My rehearser was furious: “We have hardly sung it twice, you will spoil everything!” “Nonsense”, said Cornet, “don’t let the girl imagine that it is difficult. Will you sing it?” I sang it straight away by heart, as I had worked hard at home. Then Cornet began — he sang and acted excellently and did every step, every movement, in front of me. “In two days’ time we’ll go on the stage and I’ll show you how such a part is performed”. And that is what happened. Before the week was out, I could act, speak, laugh and sing the whole part as Cornet wanted. The performances came off and I did my job well!

–o–o–o–o–o–

[1] Alois Ander (Anderle) (24 August 1821–11 December 1864) Cf: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alois_Ander

[2] Julius Cornet (15 June 1793–2 October 1860). Cf: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Cornet

[3] Mathilde Wildauer (7 February 1820–23 December 1878). Cf: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wildauer

Aufzeichnungen

von

Amalie Joachim

geb. Schneeweiss

über ihre Kindheit und Jugend

Abgeschrieben für ihre Enkelin

Nina Joachim

zum Weihnachtsfest 1956

in Frankfurt a/M.

[Seite] 2

Es war an einem Freitag, früh 9 Uhr, eben läuteten in dem kleinen Städtchen Marburg die Glocken zum Gedenken unseres Heilandes, als ich den ersten Schrei ausstieß. Es muß ein böser, lauter Schrei gewesen sein — denn unser Hausarzt Dr. Jüttner, ein Mann, den ich später sehr in mein Herz schloß, stutzte als er ihn hörte und sagte: „Herr Gott, so a G’schra hab ich von einem Neugebornen noch nie g’hört!“ Mein liebes Mutterl war schwach und konnte kaum lächeln zu dem Schrei — ward aber, trotzdem böse Rosen auf ihren Wangen erblühten und sie arg zu fiebern begann, gar nicht gleichgültig, als ich mein Schreien fortsetzte. —

Ich schrie und schrie und wies alles fort, kein beruhigendes Mittel half — ich schrie! Drei Tage dauerte dies Schreien, da sprach Dr. Jüttner endlich ein Machtwort: „Das Kind muß aus dem Haus. Die Mutter ist todkrank und kann nicht gesunden, wenn sie das Kleine beständig schreien hört. Das Kleine ist unzufrieden, es gefällt ihm offenbar auf dieser Welt nicht. Es muß aufs Land.“ Es war im wunderschönen Monat Mai und man konnte mich also gleich fort, zu einer Bäuerin, bringen! Die Frau versprach, mich und ihr eigenes Kleines redlich zu nähren, und mein Elternhaus war befreit von mir und beruhigt, denn ich war in zwar wendischen,

3

aber guten Händen. Mein Mutterl lag zu Tode erkrankt — und Sorge, schwere Sorge hielt Vater und Großpapa umfangen. Sie, um die sich alles drehte, die liebe, schöne Hausfrau und Mutter war fast sterbend. Mein Bruder, 10 Jahre älter als ich, und meine Schwester waren schon verständig genug, um für Mutters Leben fürchetn zu können. Mein Vater, welcher seine Frau anbetete — und Großpapa, welcher Onkel, Vaters und Mutters Erzieher, waren fast wahnsinnig vor Schmerz. Es war nur zu begreiflich, daß ich armes Wurm in dieser Zeit vergessen wurde. Als Mutters liebe, blaue, große Augen wieder fieberfrei in die Welt blickten, war ihre erste Frage nach mir. Ja, das Kind ist gut aufgehoben; es schrie so unaufhörlich, man brachte es fort. Mutter ließ sofort nach mir schicken — aber zurück sollte man mich nicht bringen — denn — ich schlief beständig, ein Zeichen, wie gut mir die Landluft tat. Als Mutter besser war, ausfahren durfte, war ihre erste Ausfahrt natürlich zu mir. Ich schlief. Mutter nahm mich auf — ach Gott, das ist kein Schlaf, das ist Betäubung. Da gestand das Weib ein, dass sie mir Schnaps gegeben hatte, damit ich beständig schreiendes Wesen ruhig sei. Natürlich wurde ich sofort mitgenommen — und befreit von den Schnapseinflüssen begann ich wieder zu schreien. Die Verzweiflung im Hause war groß. Endlich sagte Dr. Jüttner:

4

lassen sie das Kind schreien – wenn es größer wird, so wird es singen. Die kleine Seele hat das Bedürfnis sich zu äußern. Die Frau Rätin singen doch auch, und Musik ist den ganzen Tag in ihrem Hause, bis spät in die Nacht. Das Kind will’s halt noch toller! Vater war selig und rief: Gott gebe, daß das Mädel einmal eine gute Sängerin wird; ich will das Meinige dazu tun! So ward mein Schicksal bestimmt, bevor ich selber zum Bewußtsein kam. Ja, wenn Vaterl das Seinige hätte tun können, so wäre die gute Sängerin aus mir wohl geworden — aber!

Nun muß ich aber wohl Vater, Mutter und Großpapa vorstellen. Großpapa! Ich muß die Augen schließen und tief in mein Herz und Erinnern greifen, wenn ich ihn sehen will. Eine ganz dunkle Erinnerung zeigt mir ein altes, liebes Gesicht mit etwas unendlich Gutem und Schönem darinnen. Dies sind zwei Augensterne, so blau, so groß und leuchtend, wie sie kaum mehr zu finden. Schneeweißes Haar, ein schwarzes Samtkäppchen drauf — ein lieber, feiner zahnloser Mund, der köstlich zu erzählen weiß. Das ist Großpapa. Großpapa war der Bruder von Vaters Vater: Ignatius von Schneeweiß. Er lebte mit einer Schwester, Katharin, in Wolffsberg in Kärnten, nicht weit von dem Schlosse Arnoldstein, welches

5

meinem richtigen Großvater als Fideikommiß zu eigen war. Mein Vater war auf dem Schlosse geboren und der rechtmäßige Erbe. (Groß)papa hatte einen lieben Freund, einen aus Schlesien eingewanderten Offizier, Lindes von Lindenau, derselbe hatte ein bestimmtes Vermögen bar bei sich und wollte sich in Kärnten ankaufen. Aber die Zeiten in Österreich waren damals schlimm. Napoleon hatte die Welt in Trümmer geschlagen und tausend Existenzen stürzten mit. Wer sein Vaterland liebte, brachte Opfer auf Opfer für dasselbe. Meine Vorväter brachten ihr Bestes und legten es auf den Altar des Vaterlandes. — Man nahm die Opfer an — aber, wo blieb unsere Freiheit und wo das Geld — ?! Meine beiden Großväter, denn Lindes war der Vater meiner Mutter, verarmten. Lindes fiel in einem Gefecht, und mein Großvater Schneeweiß verpfändete der Geistlichkeit seine Güter — um das Letzte seines Vermögens auch noch zu opfern. Die Regierung löste die Güter später aus — d. h. sie belieh damit die „tote Hand“ — und Vater erhielt eine kleine Pension nach dem Tode seines Vaters. Lindes hinterließ zwei Kinder, meine Mutter und einen Bruder! Der Bruder war verschollen — man sagte, er sei Soldaten nachgelaufen, nach dem Vater fragend, als diese ausrükken mußten. Mutters Mutter war tot. (Groß)papa

Teilweise wiederaufgebaute Ruinen von Schloss Arnoldstein, durch Brand am 16. August 1883 zerstört

6

nahm Mutter zu sich, da er nicht ganz verarmt war, und auch nach dem Staatsbankrott noch Mittel hatte, anständig zu leben. Er und seine Schwester erzogen meine Mutter und verlobten sie mit dem ältesten Sohn des mittlerweile auch verstorbenen Franz von Schneeweiß, dem ehemaligen Besitzer des heute noch schönen Schlosses Arnoldstein. — Mein Vater, dessen Mutter sich wieder verheiratete, und der vom Stiefvater sehr zu leiden hatte, verließ, sobald er erwachsen war, das stiefväterliche Haus — d.h. das Schloß Arnoldstein, in welchem meiner Großmutter Mann Verwalter war — ging, wohl auf (Groß)papas Kosten, nach Klagenfurt und studierte dort Jura. In verhältnismäßig sehr jungen Jahren bekam er eine feste Anstellung im kleinen Gebirgsstädtchen Eisenerz, wohin er seine liebe, schöne Braut bald holte, und mit ihnen zog, als Haussegen, der liebe (Groß)papa, dessen Schwester mittlerweile gestorben war. Vater blieb dort nicht lange, mehrere Jahre, wurde bald als kaiserlicher Rat nach Marburg in Steiermark versetzt. Wenn Mutterchen uns Kindern später von den alten Geschichten erzählte — wie schön Arnoldstein war; — wir besaßen eine Zeichnung, welche Mutter gemacht hatte; — oder wie bös Vaters Stiefvater war, welcher Vater unter der Treppe schlafen

7

ließ, welche zum Burgverlies führte, in welchem schon vor hunderten von Jahren viele Menschen gefangen waren; oder wenn sie von den Burgen erzählte, welche die Fimilie an der Drau im Wendischen besaß, die nun längst zerstört waren, und den schönen Namen „Drachenburg“, „Draustein“ hatten, und von den Ahnfrauen, welche jetzt noch auf den Ruinen herumirrten, so war es uns so himmlisch grausig, daß man sich ganz zu Mutters Fußschemel duckte und kein Schnauferl machte. Aber auch aus ihrem Leben erzählte sie. Wie sie einmal als Kind von etwa acht Jahren vor der Tür von Papa’s(Groß) Haus getreten sei — und auf der Steinbank vor derselben ein Bübchen gesessen habe — nicht so alt wie sie, mit schwarzem Kraushaar, und sie mit Riesenaugen angestarrt habe. Sie hätte schnell die Tür geschlossen und sich hinter dieselbe gekauert und sie mußte so furchtbar weinen. Papas(Groß) Schwester, die sehr akkurat und bös war, habe aber gerufen und da mußte sie zur Arbeit springen, und sie hätte so gern das Bübchen hereingeholt. Aber daran war kein Denken. Und erst am Abend konnte sie wieder zur Tür, da lugte sie hinaus und da saß das Bübchen im Gras und weinte. Nun frug Mutter: „Was sitzest Du hier?“ Da meinte es, in dem Hause da müsse ja

8

doch sein Schwesterchen sein — und es sei so lange gelaufen, denn es käme von Wien, und die Soldaten wären längst tot, und es hungerte; und da schlug Mutterchen mit einem Wehschrei hin, so kurz es auch nur war, und die Leute kamen und besahen das Bübchen, welches denn wirklich Carl Lindes, Mutters Bruder, war. Geschichten wie diese gab es viele und sie erzählen, welches Weh in unseren Familien war; sie drangen tief in unsere Herzen und legten einen feinen Schleier über all unsere Fröhlichkeit und erweckte Sehnsucht nach einem ruhigen Glück, Sehnsucht, die unstillbar war. Und doch, welch‘ eine goldene Kindheit habe ich gehabt! In Vater, der so ernst und tüchtig war, der durch seine Stellung schweren Pflichten gerecht werden mußte — wuchs der Gedanke zu einer immer bestimmteren Form, seit mein erster Schrei ihn geweckt, daß ich Sängerin werden müsse.

Meine ältere Schwester war zart, und man hatte wohl einen Mißbegriff getan, indem man sie mit Lernen überanstrengte. Bei mir sollte alles klüger gemacht werden und ich sollte nur singen. Ha, das tat ich denn auch. Ich saß auf den Bäumen und sang mit den Vögeln um die Wette! Als ich 4 ½ Jahr alt war, bekam ich von einem alten Kantor Singstunde. Es war am ersten Oktober 1843.

9

Am 4ten Oktober war Vaters Geburtstag und ich sollte von Noten ein Lied singen. Ja, Noten kannte ich, meine Schwester hatte mich in die Geheimnisse der Schwarzköpfe eingeführt — aber Worte?! Text?! Da gestand ich tief beschämt, daß ich nicht lesen könne! Jetzt finde ich es lustig, daß man damals darüber entrüstet war, daß ich nicht lesen konnte, — habe ich doch meinen Kindern nach berühmten Mustern und ganz besonders verwirrenden Systemen das Lesen selbst in langen Wochen beigebracht — und niemand hatte sich um mein Lesenlernen gekümmert — das furchtbarre Faktum stand da: „Maltschel kann nicht lesen!“ Schwesterl mußte aushelfen, sie versprach, bis zum Namensfeste, welchem sämtliche Honoratioren der Stadt Marburg teilnahmen (wohin mein Vater versetzt war), mich in die Buchstabenwelt eingeführt und mir jedenfalls die betreffenden Worte eingelernt zu haben! Nun kamen drei schwere Tage, 23 Buchstaben waren es damals. Wie danke ich der Unbildung jener Tage, welche sich mit einem E gegnügen ließ und nicht 5 beansprucht, wie wir armen Sänger von heute brauchen müssen! Auch mit dem G waren wir bald fertig — unser lieber Dialekt kennt eben nur das Eine! Na, ich sang das Liedchen stolz aus dem Notenblatte, und noch heute

10

sehe ich den dicken Herrn Bürgermeister, welchen ich direkt ansingen mußte, vor mir, — der böse Mann lachte so sehr, daß ich ganz gekränkt war, und ich glaube, meine Kunstleistung hat ihm gar nicht imponiert. — Aber der Anfang des Vorsingens war gemacht und wie es schien, zur Zufriedenheit Vaters. Nun mußte ich mehr deutsch sprechen — unsere Dienstleute waren wendisch und wir Kinder sprachen also auch besser wendisch als deutsch. Vater begann mit mir italienisch zu sprechen — und stets hörte ich, daß dies für eine Sängerin das Wichtigste sei. So vergingen ein, zwei Jahre — gleichmäßig und nur eines Zwischenfalls muß ich erwähnen. Für irgendeinen Zweck studierten Dilettanten die Oper „Norma“ ein. (Gehört vor den ersten Vorsingeabend. Ich war circa 3 Jahre alt.) Ich durfte in die Probe, das war allerdings ein Ereignis. Aber der Eindruck, den diese Probe auf mich machte, war ganz enorm. Nun erst ward mir der Wunsch Vaters, eine Sängerin zu werden, selber lebendig: Ich kam nach Hause spät am Abend und spielte die große Szene, in welcher Norma die Kinder morden will, so lebendig den Eltern vor, daß sie ganz außer sich gerieten. Ich bat so lange, bis man mir gestattete, die Aufführung mitzumachen, was denn endlich erlaubt wurde. Ich lag die Nacht wie im

11

Fieber und begann im Traum zu singen, laut hinaus! Dann sang ich Monate immer nur „Norma“. Meine Stimme entwickelte sich enorm rasch und wurde so hoch, daß ich die Arien der Königin der Nacht leicht sang. Bei uns wurde viel musiziert, Vater spielte Geige und hatte sein ständiges Quartett. Wir Kinder durften dabei sein. Meine Schwester spielte Klavier, mein Bruder Klavier und Cello, also war für Hausmusik genügend gesorgt. Ich lernte damals viele Quartette kennen, welche ich später von Meisterhänden vorführen hörte — und wie aus alten Träumen kamen die Töne aus der Jugendzeit wieder — nur veredelter und schöner! Ich hatte mir in Vaters Zimmer ein Plätzchen geschaffen, wo ich ungesehen hören konnte, und kam die Müdigkeit zu sehr über mich — ich war ja noch so jung und man musizierte so spät in die Nacht hinein — so schlief ich auch wohl ein wenig ein; das Plätzchen war hinter dem großen Ofen bei den zwei Hunden. Mies und Bob waren meine besten Freunde, es war Mutter und Sohn, prachtvolle Tiere, und sie erlaubten so gerne, daß ich sie als Kopfkissen benützte. Oft hieß es sehr spät in der Nacht: „Maltschi soll singen.“ Arien aus Titus, Figaro, besonders also Mozart, die waren immer „auf der Walze“, und da rieb

12

ich mir den Schlaf aus den Augen und sang los. Das waren schöne Zeiten! Den Tag über im Garten unter Blumen und Vögeln, des nachts in herrlichster Musik. So wurde ich etwa 8 Jahre alt. Eines Tages sagte Mutter, sie müsse nach Kärnten, Wolfsberg, Klagenfurt wegen ihrer Besitzungen, die dort noch waren. Papa(Groß) war lange schon tot und die Besitzungen, die auf Mutter übergegangen waren, verwaltete ein Mann, der plötzlich nicht zuverlässig schien. Mutter fuhr hin mit der Post, denn Eisenbahnen gab es damals dort nicht, und nahm mich mit. — Ich war noch zu jung, um zu verstehen, weshalb Mutter so sehr viel Ärger hatte und auch viel weinte — erfuhr aber später, daß Mutter all ihr Vermögen durch unredliche Menschen verloren habe. Das war nun wohl hart. Vater hatte wohl eine „hohe“ Stellung — aber sein Gehalt war nicht so bedeutend — Mutters Vermögen war groß genug, um eine schöne Beihilfe zum Haushalt zu sein. Nach einer Woche kehrten wir heim und fanden Vater krank. Ein sonderbares Leiden entwickelte sich — und jahrelang war Vater ein kranker Mann, ein sogenannter interessanter Fall. Von nah und fern kamen Ärzte zu uns, um an Vater zu studieren, aber helfen konnte keiner. Da kam das entsetzliche Jahr 48! Mein Bruder studierte in Wien — wir lebten an der Grenze von Ungarn,

13

hatten Freunde, welche sich offen auf die ungarische Seite stellten, und Vater als k.k. Beamter mußte sich von ihnen, seiner Stellung wegen, abwenden. Wir alle hatten unter den Einquartierungen der kroatischen Truppen, die furchtbar roh waren und wie in Feindesland hausten, zu leiden. Als die Ungarn aus der österreichischen Armee ausbrachen, kam es unweit unseres Hauses, welches etwas vor der Stadt lag, zu einem Gefecht. Trotz des Verbotes lugten wir zum Tor hinaus und da sah ich denn, was ich mein Lebelang nicht vergessen werde — die armen geschossenen und zerhackten Menschen. Ach Gott! man heilte sie — um sie dann zu füsilieren!!

Und mein Bruder in Wien und keine Nachricht von ihm seit Monaten! Eines Tages kamen so schlimme Nachrichten auf Privatwegen von Wien, daß Mutter es nicht mehr aushielt, auf Vaters Büro lief, um vielleicht Gewisses zu hören. Meine Schwester war in der Schule — das Mädchen fort, um „Neues“ zu hören — ich also allein im Hause. Ich klinkte die Haustür ein und wollte eben schließen, als ein schwer tappender Schritt über die Treppe zum Flur kam — ich lief fort in die Küche und sofort unter den Herd in die Holzlage. Von dort konnte ich sehen, daß etwas Zerlumptes hereinkam und ins Zimmer von Mutter ging.

14

Mein Herz bebte, ich wußte nicht, sollte ich bleiben, schreien oder fortrennen; tat aber natürlich das Unvernüftigste und ging ebenfalls in Mutters Zimmer. Da lag auf dem Sofa etwas Bleiches, Blutendes — mein Bruder. Er lag ohnmächtig da — verhungert, verwundet, im gefetzten ungarischen Schnürrock. Ich dachte, das1 Wein für alle Dinge gut sei — und goß ihm Wein in den Mund. Da kam er zu sich — und zugleich die Eltern angestürmt, welche gehört hatten, daß ein zerlumpter Mensch ins Haus gekommen sei und gleich ahnten, daß es mein Bruder sei. Durch ein Wunder, d.h. ein Wunder, welches ein braver Kamerad vollbrachte, war mein Bruder aus Gefangenschaft und wohl auch Tod befreit. Es kam eine schwere Zeit für uns alle. Mein Bruder, absolvierter Jurist, konnte nicht in den Staatsdienst treten, da er an den Wirren in Wien teilgenommen hatte. Er blieb zu Hause, versuchte Privatdienste zu finden. — Niemand hatte den Mut, ihn zu nehmen. In der kleinen Kreisstadt wußte und kannte man alles. Der einzige Ausweg blieb — um vergessen zu machen, daß Franz (mein Bruder) sich politisch kompromittiert hatte — in Militärdienste zu treten. Dieser Rat wurde Vater auch gegeben, als er sich, selbst krank und gebrochen, nach Graz begab, um für den Sohn eine Anstellung zu erwirken.

15

Dabei hörte Vater, daß eine gänzliche Umwälzung des Gerichtswesens bevorstand und er selbst wohl bald von Marburg versetzt werden würde. Man sah also in eine unsichere Zukunft. Vater, beständig leidend, fürchtete pensioniert zu werden — umsomehr als ihm Freunde mitteilten, daß man ihm zum Vorwurf mache, daß der Sohn an den Studentenkämpfen teilgenommen hatte. Das Letztere war auf den endlichen Entschluß des Sohnes von großem Einfluß — und er nahm endlich Militärdienste an. Er trat in unser Steiermärkisches Regiment als Regiments-Kadett — etwa wie unsere Einjährigen — und wurde bald nach Livorno kommandiert. — Für uns alle ein schwerer Schlag! In Italien war die Ruhe ebensowenig hergestellt wie in Ungarn und man sah täglich neuen Kämpfen entgegen. Aber es kam für meinen Bruder schlimmeres als im offenen Kampf seinen Gesinnungsgenossen gegenüber zu stehen! Man verfolgte den Feind auf heimliche Weise. Fast jeden Tag wurden junge, blühende Italiener und Ungarn in die Kasernen eingeliefert und unsere Truppen wurden alle paar Tage dazu kommandiert, im Kasernenhof dieselben haufenweise niederzuschießen! Mein Bruder litt darunter, daß er oft dem Wahnsinn nahe war. Auch mein Vater hatte Hartes durchzumachen. Das Gerichtswesen

16

wurde abgeändert und er, der seinen Dienstjahren nach in einer großen Hauptstadt hätte müssen eine erste Stelle bekleiden, wurde in das kleine Bruck an der Mur in Oberösterreich versetzt und zwar an zweite Stelle. Es war dies der Todesstoß für unseren lieben Vater. Im Herbst 1850 zogen wir von unserem lieben, sonnigen Marburg fort nach dem kalten, tief in den Bergen liegenden, sonnenlosen Bruck — und nach einem schweren Winter, in welchem wir furchtbar litten, starb im April Vater. Der Umzug, die letzte Krankheit Vaters hat den letzten Rest des Vermögens aufgezehrt — und Mutter stand mit uns zwei Mädchen hilf- und mittellos da. Noch eine entsetzliche Entdeckung mußten wir machen. Wir hatten monatelang nichts aus Italien von Franz gehört. — Als Vater seine lieben Augen geschlossen hatte, fand Mutter in seinem Sekretär einen ihrer Briefe an Franz, auf dessen Kuvert stand: „Adressat vor 14 Tagen desertiert und noch nicht eingebracht.“ Der Brief, in welchem Mutter Franz beschwor, auszuhalten und treu seine Pflicht zu tun und in welchem sie ihm offen über Vaters verzweifelten Gesundheitszustand sprach, kam an Vater ins Büro zurück und er erhielt ihn mit Gerichtsakten ins Haus geschickt — las ihn und verheimlichte ihn der Mutter — wohl hoffend, ihn ihr vielleicht

[Es fehlt hier eine Seite im gebundenen deutschen Manuskript. Nina Joachims Übersetzung dieser Seite existiert]:

He had read it and concealed it from Mother, hoping no doubt to give it to her when he was in better health and she more hopeful. So Mother had lost both husband and son and this prostrated her. She became seriously ill and I, who was twelve, stood by her bed in despair. I can still see every chair, every picture in that room in which she was ill. Father lay dead in his own room and people surged to and fro and prayed aloud, and we could only stand dumbly there with dry, hot eyes. Her duty to us gave Mother the strength to pull herself together sufficiently to do what was necessary. Father was hardly buried before everything that we could dispense with had been sold and Mother moved to Graz with us, where she had old friends and acquaintances. Her brother still lived there and she hoped that she would be able to bring us up more easily there. Oh God, what disappointments she had to endure! Those old friends, who were poor, knew her and were at least friendly — but those who were well off, quickly withdrew or even would not know us at all when we approached them. A terrible time followed; there was no help anywhere. Mother had to wait a whole year before she received her little pension. The only thing to do was to work. Mother had magic in her hands and could do the finest knitting. She knitted the finest christening bonnets and jackets for small children, which looked like spiders’ webs, and my sister and I embroidered them. There was a big shop in Graz for such goods and the proprietor ordered and bought from us. But what a labour it was — and how little money! My sister was delicate and was supposed to practice the piano for several hours daily, as Mother thought she ought to become a pianist. But what with the embroidery and insufficient food she grew steadily weaker in health. Mother’s despair grew daily as did the pallor and weakness of the delicate, beautiful, fairy-like girl. I was healthy and strong and could stay up and work for nights on end. But Mother also worried about my voice. I could not be taught, for where was a teacher who would teach me for nothing? Mother put my name down for the city conservatorium. That was all very pleasant and I always went to the classes, but I could not learn very much there. The conductor made me sing to him. “Yes”, he said, “That is allright. Come to the auditions the day after to-morrow and sing the Aria, “Und ob die Wolke” from the “Freischütz”.

17

zum Prüfungskonzert, um die Arie aus Freischütz „Und ob die Wolke“ vorzusingen. Der bürgermeister kommt und viele Zuhörer. Wenn’s Ihre Sache gut machen, dann gibt’s was!“ Ich war selig! Was es geben sollte, konnte ich nicht denken — aber vorsingen, das war schön! Ich hatte ja seit dem lieben Marburg nicht mehr vorgesungen. In der Pfarrkirche sang ich wohl in Bruck, aber sonst musizierte ich nur mit meiner Schwester. Agathe, Ännchen im Freischütz, Gabriele im Nachtlager, Pamina, alle diese Sachen konnte ich längst auswendig — und nun endlich vorsingen! Ach Gott aber! Konzert! Die Toilette! Das Trauerkleidchen war ja neu, in welchem ich mich einstellen konnte; aber die Stiefel! Für die Ewigkeit schienen sie gemacht. Dicke Sohlen und festes Kalbleder. Mutter wollte ich nicht davon sprechen — aber Mina, meine Schwester, wurde ins Vertrauen gezogen, ob es wohl anginge, mit den Stiefeln vor dem Bürgermeister auf’s Podium zu gehen — mein Kleid war ja noch kurz! Mina wußte Rat! Schön putzen, damit sie recht glänzen. Ja, das half. Sie glänzten furchtbar, denn ich hatte wohl eine Stunde geputzt, und wenn man nicht genau hinsah, konnte man sie beinahe für lacklederne halten! Und so „schwebte“ ich die lange Straße und über’s Glacis hinein in die Stadt, in den Saal der Land-

18

stände, kam natürlich zwei Stunden zu früh. Das Warten! Die Hitze! Die Aufregung! Es machte mich ganz elend. Endlich ging’s los! Der Bürgermeister kam; er war ganz wie sein Amtsgenosse von Saardam. Dick und glänzend, und verstand wohl vom Singen soviel wie mein falscher Lackstiefel — aber, als ich gesungen hatte und furchtbar verlegen unter großem Applaus vom Podium heruntersprang — wenn ich vergnügt war, konnte ich damals nicht gehen, sondern sprang stets — eine Gewohnheit, die ich recht lange behielt — da winkte er mich zu sich und streichelte meinen Kopf und gab mir ein Samtetui, ermahnte mich, immer brav und fromm zu bleiben und entließ mich huldvoll. Ich sprang zu Mutter — welche neben anderen stolzen Müttern saß — und als wir das Etui öffneten, waren in Samt gefaßt 4 Dukaten drinn! — Das war ja nun herrlich! Mein Singen! Vier Dukaten!! Meine Seligkeit war groß und nach langen, kummervollen Jahren ein Sonnenblick! — Ich blieb als Freischülerin am Konservatorium, aber gelernt habe ich eigentlich nicht viel dort. Aber in der Stadt war eine liebe Frau, Julie von Frank, welche sich meiner sehr annahm und mit mir arbeitete. Sie war sehr musikalisch und hatte viel gehört. Ich begann mit ihr Partien zu studieren. Mir war das Auswendiglernen gar keine Arbeit und nach kurzer

19

Zeit hatte ich ein ganz nettes Repertoire. Aber ich war noch zu jung, um zur Bühne gehen zu können, und meine Gestalt noch zu kindlich. Der Direktor vom Grazer Theater ließ mich prüfen — aber der Kapellmeister, welcher nicht glauben wollte, daß ich kaum 13 Jahre alt sei, meinte, die Stimme sei wohl stark, aber ich müsse schwindsüchtig sein, da ich so zart aussehe. Als ich 14 Jahre alt war, sang ich einem Theater-agenten vor, welcher aus Wien gekommen war, und der engagierte mich gleich vom nächsten Herbst ab für das Theater in Troppau. So war denn mein heißer Wunsch erfüllt und Aussicht auf eine allmählige pekuniäre Besserung. Ja, aber was von Elend und Kummer lag hinter uns! Nur eine kleine Episode aus unserem Leben will ich erzählen — viele ähnlich bleiben besser unerzählt. Es war gegen Weihnachten und wir hatten ziemlich viel Bestellungen auf kleine Taufmützchen und Jäckchen. Wir arbeiteten Tag und Nacht — aber meine Schwester erkrankte und konnte nichts tun. Die Arbeit sollte vor Weihnachten abgeliefert werden. Der Heilige Abend kam heran — und erst spät waren die Arbeiten fertig. Meine Schwester lag zu Bette; Mutter wollte sie nicht verlassen, und obwohl Mutter mich nicht gerne allein ausgehen ließ, die Arbeit abzuliefern, so mußte

20

es diesmal doch sein und ich wurde fortgeschickt mit einem Körbchen voll der Arbeiten und dem Bedeuten, wenn ich das Geld erhalten hätte etwas Fleisch zu kaufen, um der Schwester ein kräftiges Nachtessen zu geben. Mutter und ich wollten nur etwas Eier essen, denn wir mußten ja fasten als strenge Katholiken. Fasten! Lieber Gott! Wir hatten seit Tagen keinen Kreuzer Geld im Hause und fasteten schon lange! Ich eilte also in die Stadt hinein, denn es war spät und ich fürchtete mich, über das einsame Glacis zu gehen. Einzelne hellerleuchtete Fenster sah ich schon und fröhliche Menschen dahinter, die sich freuten. Die Sorge, zu spät zu kommen und meine Arbeit nicht mehr loszubringen, die Angst, auf den Straßen fast alleine zu sein, beflügelte meine Schritte. Endlich war das Haus erreicht — alle Fenster erleuchtet — ich stürze die Treppe hinauf, klingele, endlich kommt ein Mädchen —: „Ach, Sie sind da? Jetzt? Lieber Gott, jetzt denkt niemand mehr an Geschäfte! Nun, ich will der Gnädigen sagen, daß Sie die Arbeit gebracht haben.“ Sie verschwindet und kommt mit dem Bescheid, daß ich die Arbeit dalassen könne und nach den Feiertagen Bescheid holen. Ich bat, mir etwas Geld als Vorschuß zu geben, da wir es nötig hätten. Es war mir schwer, das Wort zu sagen und

21