CHAPTER I — HUNGARY

Kittsee, 1831

temptanda via est, qua me quoque possim

tollere humo victorque virum volitare per ora [1]

Virgil, Georgics Book III

Pressburg, Hungary

ca. 1839 [i]

As far as the eye can reach into Hungary, extends a vast wooded plain, through which the gigantic Danube spreads itself wild and uncontrolled. Sometimes dividing into several branches, nearly as wide as the parent stream, it forms large islands of several miles in extent; then collecting its scattered forces, it moves forward in one vast mass of irresistible power, till division again impairs its strength. [ii]

John Paget, 1835

oseph Joachim’s birthplace lies on a sunny, fertile alluvial plain in the Austrian province of Burgenland, in a landscape reminiscent of the American mid-west. Close at hand, the Danube forms a majestic thoroughfare from Vienna to Budapest as it pursues its tortuous, 1,776-mile passage from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. On the far side of the river, five miles as the crow flies, or a scant eight-minute’s journey on the “weasel train,” stands the Slovakian city of Bratislava — the former Hungarian capital city of Pressburg, where from the year 1536 the Hungarian kings were crowned and the diets met — its large, square fortress commanding a rocky eminence where the eastward-flowing Mississippi of Central Europe wends its course to the south-southeast.

oseph Joachim’s birthplace lies on a sunny, fertile alluvial plain in the Austrian province of Burgenland, in a landscape reminiscent of the American mid-west. Close at hand, the Danube forms a majestic thoroughfare from Vienna to Budapest as it pursues its tortuous, 1,776-mile passage from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. On the far side of the river, five miles as the crow flies, or a scant eight-minute’s journey on the “weasel train,” stands the Slovakian city of Bratislava — the former Hungarian capital city of Pressburg, where from the year 1536 the Hungarian kings were crowned and the diets met — its large, square fortress commanding a rocky eminence where the eastward-flowing Mississippi of Central Europe wends its course to the south-southeast.

On the Austrian side of the river, along the road to the nearby Haydn-town of Eisenstadt, long, low hills rise in the west, while to the east the land is flat. There, great fields of corn, grain and sunflowers stretch to the horizon. This is the breadbasket of Austria. It is fruit and wine country as well, planted with 30,000 apricot trees, and long sun-drenched rows of Welschriesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Neuburger and Blaufränkisch vines. Acres of brilliant yellow rapeseed blanket the earth, sown to slake contemporary Austria’s growing demand for bio-diesel fuel. On a June day, gentle breezes ply the fields, and animate the whispering legions of sleek, trefoil windmills that pierce the vast, placid sky. It is an idyllic scene, beautiful and serene. Yet, if one could stand, like Housman on Wenlock Edge, and imagine the progress of this landscape from Roman times to the present, it would tell a tale of troubled weather. The tree of man was never quiet. The name Burgenland (“land of castles”) hints at a turbulent past. [2]

Until 1921, this region belonged to Hungary, and Joachim is considered to be Hungarian. From earliest times, the plains of Hungary have been swept by successive waves of invasion and immigration, and the resident population bears the impress of many cultures, from ancient Celts and Romans to modern Magyars, Slovaks, Germans, Roma, Turks and Jews. Joachim’s native village, the little German-speaking town of Kittsee (Hung.: Köpcsény), is located at what was once an important trans-Danubian ford, along the ancient Amber Road that originated on the Baltic coast and stretched from St. Petersburg to Venice, and from there along the Silk Road to Asia. Baltic amber found in the tomb of Tutankhamun and North Sea gems sent as an offering to the temple of Apollo at Delphi likely passed through Kittsee. In the 1830s, Kittsee was a thriving market town, and a stopping-place along the coach route from Vienna to Buda and Pest. In those days, many of Kittsee’s residents were immigrant Swabians, who, like expatriate Germans elsewhere, retained the accents and customs of their native land. Living side-by-side with them was a community of some 800 Austrian Jews who, for a century and a half, had been permitted to settle in this country crossroads and call it home.

Esterházy Schloss, Kittsee

Today, Kittsee is a quiet village, where a visitor can linger in the street at mid-day and overhear the crowing of a rooster or the lowing of cattle; where the snarl of a motorcycle or the rumble of a passing car are only occasional jarring intrusions upon the peaceful rural soundscape. At the outskirts of the town, an elegant Baroque Schloss, or manor house, gives evidence that Kittsee once belonged to the immense Esterházy land holdings in western Hungary. In the town center, the main road divides to encompass a large open area encircled by modest one- and two-story dwellings and shops. There, on a grassy island, stands a Pestsäule, or plague column, dated 1727, a prayer in stone to Saints Rochus and Sebastian, the Madonna and the Holy Trinity, commemorating Kittsee’s deliverance from the Black Death. In the town, nearly all evidence of the once-thriving Jewish community is gone.

Several blocks from the town center, around a corner, down a lane called Am Schanzl (“by the little entrenchment”), looms the imposing brick and stone ruin of the former Wasserburg, or moated castle, a 12th-Century Hungarian border defense against Austrian invasion. Today, the fortress is guarded by tall columnar poplars and fenced in against intruders, its windowless walls and caved-in floors home to a myriad of swallows.

The Wasserburg, Kittsee

On the far side of the Burg lies the Jewish cemetery — the “good place” — a sky-blue Star of David emblazoned above its stucco, iron and chain-link gate. Vine-covered stone and brick walls shaded by a dense chestnut wood enclose the small raised yard, where neglected stones protrude above the wall’s crest, or hide in the tall brown grass, like ships partially visible in a fog. Singer, Mauthner, Figdor… A funeral in this small cemetery was movingly portrayed in Otto Abeles’s 1927 article, Intermezzo in Kitsee. [iii]

Jewish cemetery, Kittsee

Between the cemetery and the main road, near the town center, a small square bears the name Joseph Joachim Platz, after Kittsee’s most famous native son. The house at No. 7, a large, square, two-story dwelling, fourteen meters from side to side, bears a plaque placed on the centennial of Joseph Joachim’s birth.

Joseph Joachim’s Birthplace, 7 Joseph Joachim Platz, Kittsee

Joseph Joachim’s Birthplace, 7 Joseph Joachim Platz, Kittsee

Memorial tablet, 7 Joseph Joachim Platz, Kittsee

In diesem Hause erblickte am 28 Juni 1831 der Geigenkünstler

Joseph Joachim

Direktor der Staatlichen Akademischen Hochschule für Musik in Berlin

(1869-1907)

das Licht der Welt

Burgenländische Landesregierung im Verein mit

Gesangverein “Liedertafel” Kittsee und

Ortsbevölkerung von Kittsee

1931 [3]

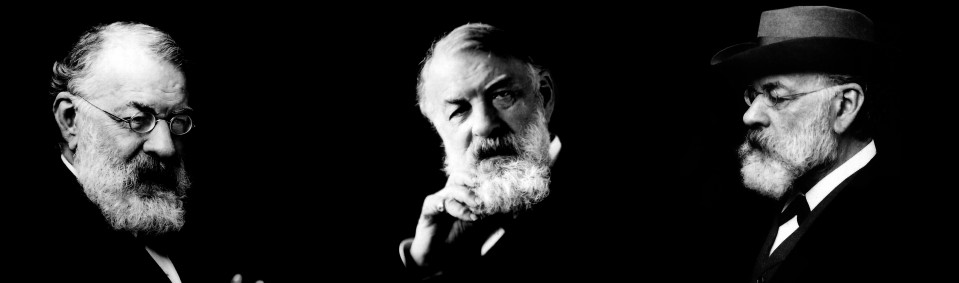

This German tablet replaced a Hungarian plaque, commissioned two decades earlier and melted down after Kittsee became Austrian. The 1911 plaque was a more elegant affair, a bronze bas-relief depicting a bearded, garlanded, middle-aged Joachim József, his face thrust forward in intimate proximity to a sensuous, violin-playing muse.

Kittsee Bürgermeister Johann Werner unveiling the Hungarian plaque, July, 1911 [iv]

Whether cast in bronze, or carved in stone, the facts of Joachim’s birth have proven difficult to establish with certainty. Joachim himself was unsure of his birth date. For the first 23 years of his life, he believed he had been born in July — either the 15th or the 24th. [4] Joachim’s boyhood friend Edmund (Ödön) Singer (b. 14 October 1831, Totis, Hungary — d. 1912) also calls into question the year of Joachim’s birth. “All reference books gave 1831 as Joachim’s birth year, as well as the birth-year of my humble self. […] Joachim himself asked me one day: ‘How does it happen that we are always mentioned as having been born in the same year? I am at least a year older than you!’ — I, myself, finally established my glorious birth-year after many years, while Joachim tacitly allowed the wrong date to persist.”[5] Though June 28, 1831 — a beautiful early summer day that ended ominously, with a thunderstorm toward midnight [v] — is emblazoned on his birthplace and engraved on his tombstone, no records have yet surfaced to verify the date of Joachim’s birth.

A more recent picture of the Joachim house (2013)

© Robert W. Eshbach, 2013.

Next Post in Series: Family

[1] I, too, must find a way to rise from earth,

And fly victorious on the mouths of men.

[2] The name Burgenland is modern, dating from around 1920.

[3] “In this house, on June 28, 1831, the violin artist Joseph Joachim, Director of the State Academic High School for Music in Berlin (1869-1907) first saw the light of the world. Regional Government of Burgenland, in conjunction with the Choral Union “Liedertafel” Kittsee and the citizens of the town of Kittsee, 1931.”

[4] Carl Ferdinand Becker, for example, in his Die Tonkünstler des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, (Leipzig, 1849, p. 82), gives Joachim’s birthdate as July 15, 1831. Joachim was living in Leipzig at the time, and was, undoubtedly, the source of this information.

[5] “Alle Nachschlagewerke gaben das Jahr 1831 als das Geburtsjahr sowohl Joachims wie meiner Wenigkeit an. Obwohl das nicht richtig ist, läßt es sich doch wohl erklären. Am 10. April 1840 trat ich zum ersten Male öffentlich in einem Konzerte auf. Ich war damals noch nicht zehn, aber auch nicht mehr neun Jahre alt, und so setzte man einfach bei den betreffenden Stücken auf das Programm ‘gespielt von dem neunjährigen Edmund Singer’. Wahrscheinlich ist es Joachim ebenso oder doch ähnlich ergangen. Joachim selbst fragte mich eines Tages: ‘Wie kommt es, daß wir überall als im gleichen Jahre geboren angeführt werden? Ich bin doch mindestens ein Jahr älter als du!’ — Ich selbst habe nach vielen Jahren endlich mein glorreiches Geburtsjahr festgestellt, während Joachim das falsche Datum ruhig weiter gehen ließ.” Edmund Singer, “Aus meiner Künstlerlaufbahn,” Neue Musik-Zeitung (Stuttgart), Vol. 32, No. 1, (1911), p. 8.

[i] Bartlett illustration in Pardoe/MAGYAR II, opp. p. 59. Author’s collection.

[ii] Paget/HUNGARY, p. 5.

[iii] Reiss/GEMEINDEN, p. 109 ff.

[iv] Photograph courtesy Dr. Felix Schneeweis, Ethnographisches Museum Schloss Kittsee.

[v] Presburg und Seine Umgebung, Presburg: Wigand, 1865, pp. 65 ff.; Wiener Zeitung, (June 30, 1831), p. 838.