© Robert W. Eshbach, 2019

The 31st Lower Rhine Music Festival

Is it not strange that sheep’s guts should hale souls out of men’s bodies?

—William Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing II, iii (1598)

The Tonhalle, Düsseldorf, 1852

On May 17, 1853 Joachim played the Beethoven concerto in what would prove to be a defining event in his career. The occasion was the 31st Lower Rhine Music Festival, held in Düsseldorf from May 15-17, under the direction of Robert Schumann. Schumann’s invitation was issued on April 17 (or perhaps the 12th — the letter seems to be misdated), a mere month before the event. “I think they will be happy days,” he wrote, “and there will be no shortage of good music. You will certainly also encounter many of your acquaintances here. So come, and don’t forget to bring your fiddle and the Beethoven concerto, which we all would love to hear.”

Joachim replied: “I am naturally always prepared to accept an invitation from you… You will believe the heartfelt delight that I felt, to be remembered by you, revered master. I had thought that it would be left to chance, to recall my name to you. How much nicer that it is otherwise…” [i] Schumann wrote again on the 18th with details of the contract: Joachim was requested to play on the third festival day for a fee of 12 Friedrichsdor — the same as David had received on a previous occasion. “My wife also requests that you come,” Schumann added. To afford Joachim sufficient privacy, Schumann arranged for him to stay nearby with a banker named Scheuer, who was a widower and agreed to put his house at Joachim’s disposal. [ii] Schumann promised to meet him at the train.

On May 9, Joachim wrote again, offering his services as a tutti player for the other performances. “The orchestra parts for the Beethoven concerto are ready,” he promised. “My violin is also in order, and looks forward with me to the rich days of music with you and your wife…” Though the Schumanns had known Joseph in Leipzig as Mendelssohn’s protégé, in Düsseldorf they would come to know and esteem him in his young maturity. In those “happy days” in May, their acquaintance would develop into a warm friendship, and, for Clara, a partnership that would sustain her through hard times to come.

Since their founding in 1818, the Lower Rhine Music Festivals had been a vital feature of German cultural life, an outgrowth of the prodigious passion for music amongst the Rhine Province’s socially vibrant and increasingly affluent middle class. The large choral and orchestral festival took place annually at Whitsuntide (the seventh Sunday after Easter), its venue alternating each year amongst the Rhenish cities of Düsseldorf, Cologne and Aachen. What had begun as an amateur festival under municipal sponsorship had gradually taken on a more professional aspect under the direction of such conductors as Felix Mendelssohn (who conducted seven times between 1833 and 1846), Louis Spohr, and Gaspare Spontini. The 1853 Musikfest was, in a way, a rebirth of the festival; due to the mid-century political troubles, it had occurred only once (1851) since 1847. Though the trend toward professionalism continued, both the chorus of 490 voices and the orchestra of 160 players were still largely made up of amateur musicians. As municipal music director in Düsseldorf, Robert Schumann was chosen to lead the event.

Like the other festivals in recent years it was a three-day affair, and programming followed a well-established pattern: the first day’s concert typically featured an oratorio (Mendelssohn’s Paulus had been composed for, and premiered at, the 1836 festival); a Beethoven symphony anchored the second day’s program, and the third day was given over to a display of “artists” (i.e. professional soloists), with attendant flower-throwing and laurel-crowning. The 1853 festival opened with the premiere performance of Schumann’s revised Fourth Symphony, paired with Handel’s Messiah. The second day’s offerings included works by Weber, Mendelssohn, Hiller and Gluck, and concluded with a performance of Beethoven’s ninth symphony. The lengthy artists’ concert opened with Handel’s Hallelujah chorus, and concluded with Schumann’s Rheinweinlied, specially composed for the occasion. Clara Novello was among the singers, Clara Schumann performed Robert’s piano concerto, and Joachim played Beethoven and Bach. Schumann led the first day’s performances, and Ferdinand Hiller conducted on days two and three.

The concert venue was prettily situated among hedges and walks in a park facing the court gardens, just outside the city limits about a dozen blocks from the Schumann’s Bilkerstrasse home. This garden spot had long been a popular recreational destination, and a privately maintained concert hall had existed there at least since 1816 (originally Jansen’s Lokal; then, after 1830, Anton Becker’s Gartensaal, and after about 1850 Geisler’s Gartensaal). [iii] Since 1818, it had been home to the Lower Rhine Music Festival in Düsseldorf. The hall was rebuilt and expanded several times. In 1852, a large new Tonhalle was erected in anticipation of an immense men’s choral contest, the “Sängerfest des Männergesangvereins” that drew vocal groups from as far away as Vienna, and overwhelmed the city with festivities from August 1-4 of that year. The Tonhalle was a rustic affair, described in 1863 as “only a provisional wooden structure, of the roughest workmanship, isolated without the necessary adjoining rooms; in bad weather not even to be reached with dry feet, not weatherproof, and, in the course of time, of very dubious safety.” [iv] Nevertheless, it had the advantage that the performances could be heard in the gardens outside its plank walls, and, for some, the added delight that the nightingales that gathered in the surrounding trees at Whitsuntide felt emboldened to join in the music making, loudly audible through the cracks and windows to the audience within.[v]

An English visitor (“ONE OF THE IDLE”) gave a charming description to the Musical Times of the festival’s cheerful, unbuttoned ambiance: “…for those who were partakers in this delightful meeting, there remains an unfading recollection of excellent music enjoyed at leisure, associated with the beaming and friendly faces of appreciating listeners. The executants and audience have an equally large appetite for music, if we judge by the length of each programme, but the way of getting through the appointed quantity conveys nothing of the business-hurry which attends your English Festivals. Here, in Germany, are long intervals for Mai-trank drinking, for smoking, and for friendly greetings in the garden-walks surrounding the Concert-Hall. At Birmingham last year there were but two rehearsals for seven concerts, — but here seven grand orchestral rehearsals, besides numerous previous small practice-meetings, are appointed for the two first concerts. Most of the chorus-singers and orchestra-players are amateurs in every sense of the word, and seem to live in the gardens while the Festival lasts, lunching and dining, and never in a hurry — the early morning hour of eight, finds them punctually present, and at the end of a long evening rehearsal, they seem as eager and as much awake as their deliberate natures will permit.” [vi]

Despite the overall cheerfulness of the event, Schumann’s direction on the first day was an embarrassment. Taciturn and bewildered, he proved to be so incapable of making his musical intentions known to the performers that they privately agreed to ignore him and follow concertmaster Hartmann instead. When the evening’s performance concluded without the anticipated disaster, Schumann responded dryly to a friend’s congratulations: “Oh, one only congratulates women after childbirth.” [vii] The critics were devastating. “Regarding the peformance of the Messiah, we have to confess, we have seldom heard one that is more inadequate,” wrote “H. W.” in the Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung. “And why, exactly? Because Schumann is no conductor. Schumann possesses absolutely none of the characteristics that qualify a practical conductor; least of all does he understand how to lead large forces securely. As the saying goes, he “lets God be a good man” — if it goes well, all is well, if it does not go well, all is well too, at least for him. […] We are not alone in this opinion; it is already well-known in Düsseldorf — indeed, very well known — and we have only spoken clearly what others have until now dared only to insinuate. Furthermore, even aside from issues of conducting technique, Schumann’s conception of the oratorio was no less inadequate — indeed, [it was] faulty — the execution, with few exceptions, practically disgraceful.” [viii]

By comparison, the second day’s performance of Beethoven’s ninth symphony was a triumph for Ferdinand Hiller. “What a different ensemble from yesterday!” wrote “H. W.” “What completely different leadership, too!” [ix] Ludwig Bischoff, writing in the Rheinische Musik-Zeitung, noted with particular pride the reaction of the visitors from France. “With great satisfaction we heard from all directions the judgments of the foreign musicians and conductors, who were all in agreement that such a “virtuoso orchestra” was a rarity. The Parisian musicians in particular, who attended all the rehearsals and performances with greatest attention, were rapturous.” He quoted them saying: “we must freely admit, we do not have anything like it in France. We cannot therefore do better than to visit our neighbors on the Rhine in order to learn, for in music they are, for once, our masters.” With Hiller at the helm, he wrote, and Hartmann, Pixis and Joachim on the first desk, “a more consummate performance of this work, which demands the highest level of artistic training from all the musical forces, is in fact hardly to be approached; it is, as with everything superhuman, only imaginable.” [x]

Bischoff also noted the importance of the third-day “Artists’ Concert” (a feature of the festivals since Mendelssohn introduced it in 1833) for the education of the public and the general elevation of musical standards: “for without virtuosi there can be no virtuoso orchestra, and the heroes of the performing art belong, with their exemplary performances most particularly in a music festival where hundreds of art lovers converge, who, in their modest spheres of influence have no opportunity to hear anything so excellent.”[xi]

At 22, Joseph was no longer a child prodigy, and the expectations that he had to satisfy were daunting. Writing in 1897, Wilhelm von Wasielewski recalled: “He already enjoyed a widespread reputation in the musical world commensurate with his high artistic standing. It is therefore understandable that the musicians of the Rheinland, who had not yet had an opportunity to hear him, were extraordinarily curious about his accomplishments, but not in a wholly impartial way. Namely, it was supposed that his reputation was in part artificially created through partisanship, and to some extent exaggerated. His first appearance in the Rheinland was therefore awaited with a certain prejudice, seemingly as an opportunity for sizing him up in the most hypercritical way. Even the decent concertmaster Hartmann from Cologne, who led the festival orchestra, was to some extent disfavorably influenced by this attitude.” [xii]

At the rehearsal, the young concertmaster from Hanover created a buzz of excitement. Yet, with all the pressure of the day’s events, Joseph’s pre-concert thoughts were with Liszt. “Dear, honored friend,” he wrote. “There would not be time for me to tell you how it is that I am writing to you from here, for the concert that I am obliged to play in will begin in a few minutes. This is my first time at a Rhenish music festival, and the whole thing has interested me greatly; I shall tell you more in person, for I shall depart very early tomorrow morning, and after staying a few necessary hours in Hanover will immediately leave for Weimar and the Altenburg. I accept with thanks your kind offer to live there; it is the best means of enjoying a great deal of your company, and therefore the most welcome. In haste From my whole heart, your devoted Joseph Joachim.” [xiii]

“A truly tropical swelter prevailed in the concert hall, which was filled with more than 2,000 people,” wrote Wasielewski. “This heat, growing with every quarter-hour, became even more palpable on the raised stage than in the audience. Many soloists would have been ill at ease under such circumstances, but Joachim strode like a youthful hero before the audience, with his own innate, aristocratic bearing, as his turn came in the second half of the concert. Then, as the audience listened with reverential silence to the sublime, almost transfigured melodies of Beethoven, carried by Joachim’s silver tones, suddenly, as in his debut in Leipzig, the E-string broke. That the most beautifully progressing pleasure could be interrupted and disturbed by such an absurd accident led to a scene of awkward tension. Involuntarily, one wondered what would happen next. Pixis, Cologne’s second concertmaster, who was standing at the first stand of violins, helped him out of the bad situation. Fortunately, he had a good, true string on his violin, which he gave to Joachim, who after a few minutes again stood before the audience and began the concerto once again from the beginning. His unique playing was magnificent beyond description and, even with regard to intonation, left not the least thing to be desired, even though the newly-stretched string did not keep its pitch in consequence of the tropical heat in the room, and had to be tuned up in convenient moments. During the Larghetto, poetically animated by the soloist, many became misty-eyed with emotion, and even the worthy concertmaster Hartmann was so overcome that bright tears ran down his cheeks. A more beautiful compliment for the celebrated master of the violin could not be imagined. A storm of applause lasting many minutes with elemental force broke out after the finale. The audience could not be quieted, and let it be known, through sustained applause, that Joachim should give them something more… and so, despite his overheated and wearied state, Joachim had in the end to comfort them with an encore, which was nothing less than Bach’s Ciaccona for violin solo. It was, under the circumstances, an astonishing achievement.” [xiv]

In the ensuing days, the international music press was full of praise for Joachim’s performance. “As for the Beethoven Violin Concerto in D Major, we confess that we have never yet heard anything more perfect,” wrote “H. W.” in the Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung. “Such a work, performed with such mastery, with such profound penetration into the spirit of the composition, is a pleasure that, in our time, is like an oasis in the desert. We wish to acknowledge the individual merits of all our German masters of the violin; but we have never heard any of them play ‘Beethoven’ in such a way as Joachim does. Here is Classicism from the first to the last stroke; not a Classicism that coquettes with form — no, such as it is ‘in spirit and in truth.’” [xv] Again, the German press seemed to take particular pride in foreign opinion. The Zeitung für Norddeutschland quoted the Indépendance Belge: “The ‘lion’ of the festival is Joachim. We have known his name for a decade. Mendelssohn took him under his wing in London, where the young Joachim accomplished wonders. Since then, the Wunderkind has become an artist, a very important artist. A pupil of David and Spohr, matured through the advice and friendship of Mendelssohn and Liszt, Joachim already realizes the highest ideal that one can dream of. Under his magical bowstroke, the colossal concerto of Beethoven becomes even more powerful. The master’s nobility of style, grandeur of expression, profundity of thought — all this, Joachim has understood, and he renders it all with the simplicity of genius and the warm and intimate passion of the great poet.” [xvi]

Clara Schumann, who, in the practice of the time accompanied Joachim for the Chaconne, afterward recalled: “Joachim was the glory of the evening. Though the rest of us also got applause to be sure, and though after Robert’s concerto I got a laurel wreath from the orchestra and much applause from the audience, nonetheless Joachim won the victory over us all with the Beethoven concerto — but he also played with a perfection, and with such deep poetry, with such soul in each little note, really ideal, that I have never heard such violin playing, and I can truly say that I have never received such an unforgettable impression from a virtuoso. And how the great work was accompanied — with what perfection! It was as if a holy devotion possessed the whole orchestra.” [xvii]

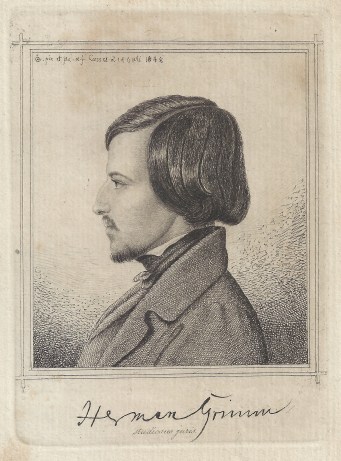

Carl Reineke, who was also present on the occasion, recalled the event many years later: “What a different person, how much greater he had become in the meantime. Once an acolyte of virtuosity, now a priest of art. He played the Beethoven violin concerto, hitherto unapproached by any interpretation, and recognized in its full greatness only from that moment on, since Joachim made it his own. Like a youthful hero, nobly, but modestly, he appeared on the podium… It is an idle thing to describe such consummate playing. But even today, after fifty six years, I remember clearly that I stole through the loneliest walks of the court gardens, to relive this artistic event inwardly.” [xviii]

“I don’t care to think of any other violin,” Clara wrote in her diary the day after the festival. That day, she and Joseph had performed Schumann’s a minor sonata for a small circle of friends. Joseph had played “so wonderfully that for the first time the work had created the impression that I had always imagined it could.” “It is not just as an artist that we have come to know Joachim, but also as a sweet, genuinely modest person. He has a nature that requires a longer and closer acquaintance to be properly appreciated, which is, in fact, the case with all excellent people!” [xix] Robert noted a simple mnemonic in their Haushaltsbuch: “18. May 1853 Joachim’s performance of my sonata.” Several years later, in the asylum at Endenich, the memory of the performance had not left him. Visiting him there, Brahms wrote to Clara: ”Of Joachim he spoke with an enthusiasm he normally reserves only for speaking of you. He spoke a lot about the Music Festival, how wonderfully J. played even in the rehearsal. That no one had ever had any idea the violin could produce such a tone.” [xx]

An Joachim.

könnt’ ich Dir’s mit Deiner Sprache sagen,

könnt’ ich Dir’s mit Deiner Sprache sagen,

Was ich gefühlt bei Deinen Zauberspiel:

Das wär’ ein Lied, das über Erdenklagen

Wie ein geheimnissvoller Schleier fiel!

Hielt mich ein fabelhafter Traum umschlungen,

Der mir Elysiums Gefilde wies? —

Du hast den Traum mir in die Brust gesungen,

Den Traum der Seligkeit, so mild, so süss!

Wie oft sich mischt in uns’rer Kindheit Thränen

Der liebevollen Mutter Schmeichelwort,

So lösest Du des ersten Mannes Sehnen

In einen sanften, weichen Moll-Akkord. —

Des lichten Traumes Bilder sind zerronnen,

Vorbei die süssen, holden Melodie’n,

Doch lange werden der Erinnrung Wonnen

Mir wunderkräftig durch die Seele ziehn!

Cöln G. H.

[Rheinische Musik-Zeitung für Kunstfreunde und Künstler, Vol. 4, No. 209, (December 31, 1853), p. 1464]

See posts:

Concert: Düsseldorf, May 17, 1853 Dwight’s Journal of Music, vol. 2, no. 11 (Boston, 18 June, 1853), pp. 86-87.

Concert: Düsseldorf, May 17, 1853 Rheinische Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 3, No. 154 (June 11, 1853), pp. 2128-2129.

Concert: Düsseldorf, May 17, 1853 Zeitung für Norddeutschland; Hannoversche Morgenzeitung, No. 1137, (Sunday, May 22, 1853).

Concert: Düsseldorf, May 17, 1853 Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 2, No. 24 (June 13, 1853), p. 95.

[i] “Daß ich recht von Herzen erfreut war, daß Sie, verehrter Meister, meiner sich erinnern, werden Sie mir wohl glauben; schon hatte ich gemeint, es würde dem Zufall überlassen bleiben, meinen Namen Ihrem Gedächtnis einmal zurückzurufen. So schöner, daß es anders kömmt!” Moser/JOACHIM 1908, I, p. 150. Joachim/BRIEFE I, p. 53.

[ii] There were two bankers named Scheuer residing in Düsseldorf at the time: one who lived in the Kasernenstraße, and one who lived in the Carlsplatz. They were both within blocks of the Schumann’s Bilkerstraße home, and both were convenient to the concert venue.

[iii] See: Bernhard R. Appel, Geislers Saal und die Tonhalle. Zur Geschichte zweier Konzertsäle in Düsseldorf (1818-1864), in: Neue Chorszene, Vol. 16, No. 1 (January 2012), 34-42.

[iv] … “nur ein provisorisches Bauwerk von Holz, in der rohesten Bearbeitung, isoliert ohne die notwendigen Nebenräume; bei schlechtem Wetter nicht einmal trockenen Fußes zu erreichen, undicht und im Laufe der Zeit von sehr bedenklicher Sicherheit.” Apel/GEISSLER’S p. 41. “Zit. nach Hugo Weidenhaupt, Mit Jansens Garten fing es an, in: Tonhalle Düsseldorf Vom Planetarium zur Konzerthalle, Düsseldorf 1978, S. 56.

[v] Clara Novello: “In summer we went to Düsseldorf, for the Festival, Schumann conducting; he was beginning already to give signs of the sad mental illness which overcame him later, and was shy and strange in many ways. One evening a pretty incident happened: a number of nightingales came and perched on the high windows above the orchestra, and seemed excited to outsing Alceste’s divine song — till the audience and I turned our attention in delight to them.” Clara Novello, Clara Novello’s Reminiscences, London: Edward Arnold, 1910, pp. 152-153.

“Düsseldorf is encompassed by extensive park-like shrubberies, occupying the site of the old fortifications, where singing birds become tamest of the tame. At Whitsuntide nightingales abound, and day and night maintain their tuneful contests. Their reputed love of solitude seems not to hold good here, for they continue their song in loudest combination with the laughter and gossip of the festival-keepers. In the more piano passages of the concerts, the bird-songs made themselves audible; and the audience were enthusiastic when two nightingales poured forth their insisting notes close to the windows, joining in the passionate recitatives of Gluck’s Alceste: ‘Three nightingales at once’ burst forth in a shout, as the opportunity offered to vent their delight at the clear high notes of Clara Novello. At a moment of intense enjoyment how electrical is the effect of any additional accident which brings in new joy! Weak, indeed, are words to record the excitement of such a moment … ” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 5, No. 109 (June 1, 1853), p. 197

[vi] “The Niederrheinisches Musik-Fest,” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 5, No. 109 (June 1, 1853), 197.

[vii] Wasielewski/SCHUMANIANA, pp. 39-40.

[viii] “Das 31. Niederrheinische Musikfest zu Düsseldorf,” Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 2, No. 23 (June 6, 1853), p. 90.

[ix] “Das 31. Niederrheinische Musikfest zu Düsseldorf (Schluss),” Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 2, No. 24 (June 13, 1853), p. 94.

[x] “Das 31. niederrheinische Musikfest,” Rheinische Musik-Zeitung für Kunstfreunde und Künstler, Vol. 3, No. 50 (June 11, 1853), p. 1225-1127, passim.

[xi] ibid. p. 2127, recte: 1127.

[xii] Wasielewski/SIEBZIG p. 80.

[xiii] Weimar GSA 59/19, 15

[xiv] Wasielewski/SIEBZIG pp. 81-82.

[xv] “Das 31. Niederrheinische Musikfest zu Düsseldorf (Schluss),” Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung, Vol. 2, No. 24 (June 13, 1853), p. 95.

[xvi] Zeitung für Norddeutschland, No. 1137 (May 22, 1853).

[xvii] Litzmann/SCHUMANN II, p. 278. [m. t.] To Hermann Härtel, she wrote [19 May]: “Joachim played the Beethoven concerto with a perfection such as I have hardly heard from a violinist, with such genius, so nobly, so simply and yet moving to the core! He also received an ovation such as I have never yet experienced; was deluged with flowers, and then played the Chaconne of Bach as an encore.” Schumann/TALENT, p. 105.

[xviii] Reineke/ERLEBNISSE, pp. 261-262. m.t.

[xix] Litzmann/SCHUMANN II, p. 278. [m. t.]

[xx] Avins/BRAHMS, p. 95.