Music. A Monthly Magazine. Vol. 9, Chicago: Music Magazine Publishing Company (November 1900-April 1901), pp. 42-54.

An interesting, and flawed, account, mostly valuable for its first-hand reporting.

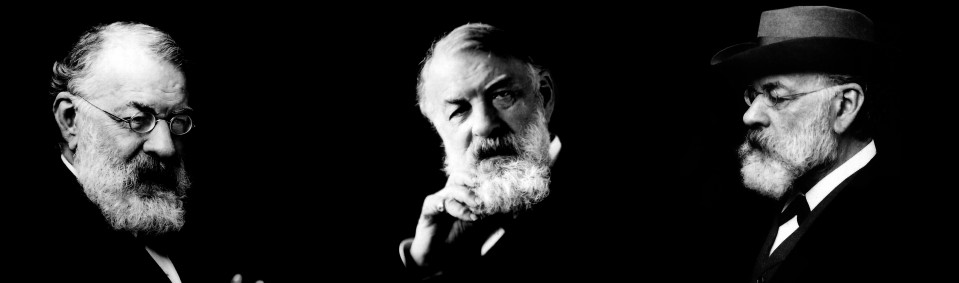

JOSEPH JOACHIM

BY EDITH L. WINN

On the 28 of June Joseph Joachim, the eminent director of the Royal High School, Berlin, celebrated his 69th birthday. You may call him an old man, but he walks with a firm step, his eye is keen, his memory is unimpaired, and his soul is as full of music as of yore. He teaches and concertizes still, and I cannot believe that his influence is waning. A Leipsic teacher writes, however, that he plays no more with the old fire. Another critic calls his quartette work scholastic and severe but perfect.

Viotti once gave this advice to De Beriot: “Hear all men of talent, profit by everything, but imitate nothing.” This advice need not have been given to Joachim. He is unique.

It seems invidious to assume that Joachim outranks all other violinists of to-day. Sauret has a wonderful repertoire and a magnificent technique; Sarasate fills us with admiration of his poetic and beautiful interpretation of the modern romantic school; Ysaye is a noble exponent of the Belgian school, and his repertoire is perhaps broader than that of Joachim, who has narrowed himself by his own choice to the severely classical.

What does Joachim stand for? He stands for dignity and sincerity in his art. He has evinced that thorough uprightness, that firmness of character, earnestness of purpose and an intense dislike of “clap-trap,” which have made him a power in the musical life of our day.

Who better can interpret the concertos of Beethoven, Bach, Spohr, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Viotti and others? He plays magnificently his own Hungarian concerto. He does not dislike the works of Wieniawski and Vieuxtemps. Last year the Second Concerto of Saint-Saëns made its appearance in the Royal High School and was not cast out! You know the German antipathy to the French school.

I have just looked over some Joachim quartette programs. It is true the quartettes of Hayden [sic], Mozart, Mendelssohn and

43

Brahms occur often on these programs. Beethoven holds first place. But do not these classic masterpieces tax the highest genius and skill in the executant?

Joseph Joachim is undoubtedly their leading exponent. I do not say that he is a genius.

There are other quartettes in the world. They may present a fresher and more invigorating program than the usual one of the Joachim quartette. This is not finding fault. I think one’s musical anatomy needs varied food.

I said that Joachim was unique. So he is as an interpreter. As a composer he has been influenced by Mendelsson, Schumann, and Brahms. He is really a follower of Schumann. Most of his works are of a grave character. Is Hungarian Concerto (op. 11) holds high rank. “It is a composition of real grandeur, built up in noble symphonic proportions,” says Sir George Grove. His most important works are a Romance for violin and piano, Concerto in G minor, Overture to Hamlet (for orchestra), Nocturne in A for violin and small orchestra, Scena der Marfa (from Schiller’s unfinished play “Demetrius”) for contralto, solo and orchestra, and, lastly, the transcriptions of the Brahms Hungarian Dances. I may also mention his beautiful Cadenzas to the Beethoven and other concertos.

Professor Joachim has been mentioned in prose and poetry. George Eliot introduced him into her poem “Stradivarius”; the author of “Chas. Auchester” used him as a type in connection with Mendelssohn; Dr. Kohut wrote his life; Herr Andreas Moser, his pupil and friend, wrote his “Lebensbild”; Carl Courvoirsier [sic] wrote an excellent treatise on his method. And Joachim is not spoiled, and he is honest and serious!

It may be interesting to readers to know something of his surroundings. Last summer I was twice a week a timid and very agitated knocker at his door. He lives in an unpretentious dwelling on Bendler strasse, Berlin. You will mount three flights of stairs and, catching your breath, you will examin [sic] his door plate, upon which is fastened a card announcing his “Sprechstunde.” After knocking and ringing the bell violently, a pale maid will appear, who will notify you that it is a pleasant day! You will be glad to hear it, for your feelings will be cloudy. You enter a dim hall and look about. You finally grope your way to one of the many hat pegs and try to

44

put your hat on a vacant peg. Straw hats, felt hats, soldiers’ caps, ladies’ hats, gentlemens’ hats— all oppose you. You will quietly put your hat on a neighboring table and be contented. As you pass into the salon you notice the two great wooden music stands used by the Quartette. You are overawed! You enter the salon. It is in elegant taste and gloomy, as is the case with nearly all German salons. There are portraits of Count von Moltke, the tried friend of Joachim, Clara Schumann and other musicians. There are busts of Brahms. There is a grand piano that does not invite you to play. Later you go into Professor Joachim’s studio. It is more comfortable. Count von Moltke still looks down at you, and Bismarck also. A bust of Clara Schumann gazes at you as you play. (Marble looks at you sometimes.) There are stiff-backed chairs there which suggest to you not to sit down in them. There is a dignified solemnity about the whole place. You look into a little office beyond, and you see a desk and a pretty piano. You feel like throwing papers all over the floor, just as Liszt used to do in his home.

On the whole, the house of Joachim is elegant and full of repose, but not comfortable. German houses are rarely cosy.

The violinist himself is far more interesting than his home. He is of middle-height, heavily built and very robust. This year he has not been in as good health as usual. His fine large head, crowned with a wealth of gray hair, might easily be the head of a scholar as well as of a musician. At first sight he resembles James Russell Lowell. The resemblance ceases when you see his impassioned manner while playing. He is quiet and reserved, dignified and serious. He is a man of very few words. Herr Moser in his “Lebensbild” says that it was only after artaking of a fine bottle of “Schlussel wein” that he was able to gather a few incidents in the artist’s life. If Joachim became talkative under such stimulant, we are indeed glad, for we knew little about his early career until his “Lebensbild” appeared.

Professor Joachim has several children. One of his daughters is an opera-singer, another is a reader. His son Johannes is a good-natured young man, who has the misfortune of being musical and somewhat clever, but shadowed by the greater talent of his parents. It is always so in life. Poor Siegfried Wagner!

45

Herr Carl Markees, one of Joachim’s favorite pupils, also lives with him, and is as devoted to him as the son could be.

HIS CHILDHOOD

Every great man has not an interesting childhood. Joachim has been singularly favored. Fortune has always favored him. No man in the world has so many musical associations as he. Allow me to quote from Herr Mosers work:

“About an hour’s ride to the south of Pressburg, the old Hungarian crowning-city, there lies, on a wide plain, the little country town of Kittsee, whose name is familiar to our school boys through Otto Hoffman’s story, ‘Prince Eugene, the Noble Knight.” In the spring of 1863 King Leopold I. held there a review of his troops. There ere long the Turks fought the Hungarians, and there Prince Eugene of Savoy offered to the king his services, which in the face of the dangers of war were gladly accepted. Kittsee to–day is called Hungarian Kopeseny [sic]. That does not hinder the inhabitants from using the German language in local trade almost entirely. They are industrious Schwabians [sic], whose ancestors a hundred years before emigrated from the empire. They have the manners and customs and habits, as well as the employments, of the old home, but in such purity are they preserved that one thinks during intercourse with them that he is in the mother country.

“Among these brave Schwabians was born, on the 28th of June, 1831, the hero of our book, Joseph Joachim. He was the seventh of eight children, with whom, in the course of years, Julius and Fanny Joachim were blest. As the parents were of Jewish birth, the children were reared according to the Jewish religion. The father, Julius Joachim, was an excellent merchant, an earnest and reserved character, but attached to his family with all his heart. Through continuous industry and steady work he had reached affluence, a certain opulence and easy circumstances which placed him in a position to bestow upon his children a good education, according to their capability. Frau Fanny was a true helper to her husband, and she watched the actions of her children as a loving and tender mother, and fitted with her plain common-sense harmoniously into the circle which is enclosed a comfortable picture of a happy family life.

“In no way burdened by worldly possessions, the family lived

46

in such well-regulated relation that they were supplied with all the necessaries of life. A more difficult question yet presented itself concerning the instruction of the children, as the educational advantages of so small place as Kittsee were soon exhausted. Commercial enterprise and the wish to furnish his children with a satisfactory education induced Julius Joachim to leave Kittsee and remove to a larger city. The year 1833 finds the Joachim family in Buda-Pesth. The Hungarian capital is the real scene of the childhood and early youth of the little Joseph, or rather, ‘Pepi,’ as we must call our little one according to the Austrian custom.

“In the Joachim family music played no important part. They heard it gladly, but a deeper interest had not existed.

“Only the second daughter, Regino [sic], possessed so pleasant a voice that her parents allowed her to take voice culture. The singing of the sister first awakened the musical sense of the little ‘Pepi,’ who with close attention, listened to every tone and strained every nerve to reproduce the songs of his sister upon a child’s violin. There was a medical student, a frequent visitor in the Joachim family, who played earnestly upon the violin during his leisure hours. It was he who first noticed the wonderful musical inclination of the little one, and it was he who first introduced our ‘Pepi’ into the elements of violin-playing upon the child’s fiddle.

“The musical intelligence of the child and the wonderful progress which he in a very short time made upon the plaything induced Stieglitz to call the attention of the parents to the wonderful talent of their little son, and to advise them to allow the child to have lessons regularly from a professional teacher. Here the good sense of the father is shown in the best light. Though living in very modest circumstances, he did not employ any teacher but the best in Pesth, Serwaczynski, the the the the the the theconcert-meister of the opera there.

“Serwaczynski was born in 1791, at Lublin, and died in the same place in 1862. He was a clever artist, who took seriously his work as a teacher of the little ‘Pepi.’ Not only has a violin teacher did he influence his little pupil, but gradually as a house–friend in the Joachim family, did he win an influence over his pupil morally. ‘Pepi’ was a timid child and afraid of the dark. That did not please his teacher, and he resolved to rid

47

him of his weakness. One evening he demanded of the child that he should go into another room, and ‘Pepi’ was urged by all sorts of promises to go through a dark corredor to the distant room. Serwaczynski tried to encourage him in every way but, finally, unsuccessful, scolded him and went out of the house with the remark that he would no longer instruct such a ‘hasenfuss.’ [sic] The next day the teacher did not come to the accustomed lesson, so the child went to him and begged his pardon, saying that in the future he would be no longer so silly, if only he could have his beloved violin lessons again. That experiment of the teacher was successful, for the teacher kept his word. Aside from the violin the general education of the child was not neglected. For the first school year he was sent to the public school. The following year he was sent to a private school after home of the present Concert-meister, at Stuttgart, Edmond Singer, with a few children of the same age.

“Our little hero made such fine progress in violin playing that Serwaczynski asked the parents that he might take the child to the opera, there to become acquainted with a larger musical life. This first visit to the opera made a grace and lasting impression upon the child. Serwaczynski played a Kreutzer Concerto (G) with orchestra. Between the acts “Pepi’ was allowed to enter the orchestra and obtain the first glimpse of its arrangement, with which later he should become so intimate. There the teacher showed his little pupil the instrument upon which he played and the picture was so impressed upon his memory that thirty years afterward, in a concert tour through Sweden, he recognized the instrument there. He was asked, by the Polish violinist, Biernacki, who had bought from Serwaczynski, to buy the violin. Joachim did so, and the violin of his first teacher, a beautiful and well-preserved Andreas Amati, is to-day in his possession.

“After the boy’s first visit to the opera, followed by other visits, he naturally hungered for music, as soon as he first observed that there was another music in the world besides his violin lessons. The opera at Pesth was, moreover, at that time not so bad. It held on to traditions. Was not Beethoven there for the opening of the theater in 1811, and did he not write the music to ‘King Stephen’ and the ‘King of Athens’ for that occasion?”

I will not quote further from Herr Moser’s most interesting

48

book. Little ‘Pepi’ made his first public appearance on March 17th, 1839, when he played with his teachers the double concerto of Eck and played alone the variations upon Schubert’s “Trauerwalzer,” by Pechatchek. The boy won laurels and attracted the attention of the Graf von Brunswick and his sister Therese. The former had been a most intimate friend of Beethoven.

Soon after this time there came a visitor to the Joachim home Frl. Fanny Figdor, a cousin of the family and a musical lady. She induced the father to send his little son to Vienna. There he remained for several years. In this broad musical center, influenced by the French School, and still influenced by Spohr, the boy was reared. Mayseder was his warm friend; Clement, the eminent violinist, was interested in him. A third influence came to the Boy. It was that of Bohm [sic]. This eminent violinist was a follower of the school of Rode. His famous pupils were Hellmesberger, Ernst and Joachim. Bohm was a great quartet player. The first teacher of the boy in Vienna was Miska Hauser, a pupil of Mayseder. These lessons lasted one month. About this time Ernst came to Vienna and his playing caused a furor of excitement. The little Joachim heard him and was stimulated to greater effort. To Bohm Joachim owes a great love for and broad training in quartette literature. Bohm was one of the greatest quartette players of his day. He was like most German professors, a hard task master. Sometimes his pupil displeased him, and he would shout out, “Verflixter Bub, wirst gleich ordentlich geigen!” Herr Bohm’s wife was an irascible lady, and often roundly scored the boy for his seeming negligence. All this did the boy good. In a short time he played the Rondo from the E major concerto by Vieuxtemps and the Othello Fantasie by Ernst, at the Conservatory.

Great artists came to Vienna to concertize, and Joachim had the opportunity to hear them play. Among them were Ernst, De Beriot and Vieuxtemps, Mendelssohn, Klara Wieck, Liszt and others. For Schubert and Beethoven Joachim had great reverence. Meister Bohm allowed his pupil to come to those wonderful Quartette-Evenings at his home, and the boy learned to love Beethoven’s quartettes with all the intensity of his nature.

49

In 1843 he found an opportunity to go to Leipsic, the musical center of Germany. Here he met Mendelssohn, and they played together the Kreutzer Sonata of Beethoven. This was the beginning of a broader life. Mendelssohn loved the boy from the first. Moritz Hauptmann was then the cantor in the famous St. Thomas School and a teacher in the Leipsic Conservatory. Hauptmann taught him harmony and counterpoint. Bohm had given him a fine technical foundation. It was thought that David, a powerful influence at the Leipsic school, could aid the boy. They worked upon the Spohr concertos, Bach Airs and the Beethoven and Mendelssohn Concertos. These works constituted the boy’s repertoire. Ferdinand David was a great violinist. He interpreted Bach well, and he revised and fingered the most classical compositions of the day. He was a friend of Mendelsson and Schumann. His influence was powerful. He could not bearn to hear his young pupil play upon an inferior violin. He often said: “A real artist should play only the best!” He objected to the frequent use of the rubato, and the use of the spring-bow in classical compositions.

The first great concert at which the boy played in Leipsic was in 1843, when Pauline Viardot Garcia appeared at the Gewandhaus. Mendelsson played the variations for two pianos by Schumann, with Clara Schumann, and Joachim played with Mendelssohn an Adagio and Rondo by de Beriot. The boy’s success was assured. Not long after this he played the Othello Fantasie with Mendelssohn as an accompanist, in the Gewandhaus. His success the first year in Leipsic was so great that Hauptmann wrote to Franz Hauser: “Joachim from Vienna, who has learned so rapidly, is here. He has much talent, has studied with Bohm, plays perhaps an hour daily, and has played the Spohr Gesangscene recently with David in the Gewandhaus; so beautiful was his tone that Spohr himself would have been filled with joy.”

We next hear of Joachim in London, where, in 1844, he played with Mendelssohn at the Drury Lane Theater the Othello Fantasie by Ernst. Mendelssohn called him “My Hungarian boy,” and showed a wonderful interest in him. This trip was followed by a concert tour in which he appeared on programs with Lablache, Thalberg, Sivori and others.

50

London rang with his praises when in 1844 he played under Mendelssohn’s direction, for the first time, Beethoven’s Concerto. Mendelssohn wrote immediately to Leipsic of his wonderful success.

From that time Joachim has made annual tours to England, where he is universally beloved. The London public claim him for the Crystal Palace Concerts and the Popular Concerts. Provincial towns compel him to spend several months of the year in a concert tour, and Joachim may well say that England is almost as dear as Germany to him.

On Joachim’s return to Germany he was placed in the care of the captain of a vessel bound for Hamburg. Somewhat curious in disposition, he one day opened the door of a cabin and there found a passenger who had cut his own throat and had just expired. Imagine the effect upon a high-strung, thirteen-year-old boy!

In the winter of 1844-5 Joachim played at a concert the remarkable concertante for four violins by Maurer. Ernst, Bazzini and David played with him. When it came time for Joachim to play his cadenza, so well did he play that Ernst shouted aloud, “Bravo!”

Shortly after this time Spohr came to Leipsic and his visit made a lasting impression upon the boy. Schumann having heard Joachim play the Kreutzer Sonata with Mendelssohn was filled with joy, and from that time the boy was a frequent visitor at the Schumann’s. Mendelssohn took great interest in Joachim’s work in composition. An interesting little story is told concerning this. Mendelssohn went away on a journey, and on his return Joachim brought him two Sonatas for violin and piano, which he had composed during Mendelssohn’s absence. The great composer said, “You write a very good hand!” Upon this Joachim remarked that the copyist had written the notes. “Simpleton,” replied Mendelssohn, “that makes no difference. It has been naturally your composition.”

Many tales are told of Liszt’s wonderful popularity in Leipsic. Mendelssohn once sent the boy Joachim to take his greetings to the great pianist. The boy he was fascinated by him. Not long after Joachim played the Mendelssohn concerto to him, and Liszt accompanied to him upon a grand piano. To the astonishment of the boy the pianist played the finale with a lighted

51

cigar between the first and middle fingers of his right hand.

In 1847 Joachim again went to London, where the “Elijah” was to be performed under Mendelssohn’s direction. In November of the same year Mendelssohn closed his eyes forever. The loss to Joachim was very great, for the boy had won a place much through the influence of his great friend.

Of Joachim’s entrance to the Gewandhaus orchestra and his subsequent engagement as a teacher in the Leipsic Conservatory, there is not much to say. He cared no more for Leipsic after the death of Mendelssohn, and when the opportunity came to him to go to Weimar he went willingly.

Liszt was in the zenith of his power there. Hauptmann wrote to Spohr in Paris: “Beloved Herr Kapellmeister—We have lost Joachim, our accomplished violinist and beloved man. So through and through a musical person as he we shall not be able to obtain.”

What a wonderful old town Weimar is! It seems as if the spirit of Sebastian Bach hovers there still, where he labored so long as organist and choir master. Hummel, too, and Goethe live in the very air of the place. And Liszt! There he stood for a new epoch in music. The Wagner influence was growing. Weimar was alert, positive and negative, ready and unready for the musical upheaval.

Raff was Liszt’s secretary, and he, von Bulow, a student of Liszt, and Joachim, formed a great friendship: Joachim played publicly the Kreutzer Sonata with von Bulow, and the latter’s mother wrote to her daughter: “Hans played the great Beethoven Sonata with Joachim, both very wonderfully. Such an interpretation as theirs cannot easily be found. Joachim is a pleasant man of attractive appearance. Hans loves him very much.”

Shortly after that Joachim went to England, and while there wrote to Liszt again and again, thanking him for his friendship and encouragement. There is no question but that the young concert meister, for so he now was in Weimar, valued Liszt and felt for him a sincere regard. Among his friends in Weimar may be mentioned Hermann Grimm and the von Arnims. At the house of the von Arnims there were many evenings of chamber music in which Liszt, von Bulow and

52

Joachim often participated. There came a time when the young Joachim felt the growing power of the Liszt-Wagner cult. True to Schumann and Mendelssohn he felt that he must stand for what seemed to him the real. He was honest. He did not break suddenly away. It was a sad time for him. Liszt knew that Joachim did not love his music. In his characteristic way he said to him: “Dear friend, I see already that my compositions do not please you.”

Liszt, magnanimous to a great degree, wrote to Stern in Berlin: “I profess great admiration for Joachim’s talent. He is an artist hors ligne, of great ambition and a glorious reputation. He has a nature altogether loyal, a distinguished spirit and a character sweet and of singular charm in its rectitude and seriousness.” He goes on to urge Stern to engage Joachim for a Berlin concert. That concert was Joachim’s first in the capital. He played the Beethoven Concerto with immense success. The National Zeitung said: “We must not let this violinist leave our city; we must retain him at any price.”

He was then twenty-two years of age. He now left Weimar, but it has never forgotten him. Von Bulow’s farewell letter to him was such a one as a great musician may write to another, though they may have had diverging lines of thought.

The year 1851 finds Joachim in Hannover, where he took the place of Hellmesberger as Concert meister.

The friendship between Schumann and Joachim continued. Often the composer wrote from Dusseldorf to Joachim to come to him and not forget his violin and the Beethoven Concerto.

Joachim’s Overture to Hamlet was first played in Hannover. Both Liszt and Schumann wrote praises of it.

It is strange, indeed, that Remenyi (then very popular) and Joachim, together with Liszt, should have held so high a place at the same time, and all Hungarians by birth.

Dr. Kohut says the Hungarians are among the most musical people in the world. There is not much that is especially eventful in Joachim’s life in Hannover. His relations with his patron, King George, were very cordial. He was allowed frequent concert journeys, and, during this time, was in Russia, France, Austria, Hungary, Holland, Sweden and Italy, making a great reputa-

53

tion as a quartette player as well as a soloist. As for England, he rarely missed a yearly visit. In 1868 Joachim came to the Royal High School in Berlin as director. There he showed his wonderful executive power and ability to organize and control. He had the advantage of excellent associates, Waldemar, Bargiel, Ernst, Rudorf and Dr. Spitta. He organized the famous Joachim quartette, consisting of de Ahna, Hausmann and Wirth. He has concertized, taught and directed orchestras. He has lived quietly and as becomes a sane man who makes no pretensions to extraordinary genius. Among the violin teachers at the Royal High School may be mentioned Heinrich Jacobson, Johan Kruse and Emanuel Wirth, Robert Hausmann, the cellist, and Heinrich Barth, pianist, owe much to him. He has inspired all who have been associated with him. His pupils are in Austria, England, Russia, Sweden, Denmark, Holland and America. If you asked him what composers he loved best he would say: Bach, Bargiel, Beethoven, Brahms, Cherubini, Ernst, Henselt, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Pallestrina [sic], Spohr, Schubert, Schumann and Weber. The members of his Quartettes have traveled all over Europe since 1870. At every Beethoven Fest Bohm looks for them. The Crystal Palace Concerts are not complete without them. Italy, Austria and many other countries have them yearly. The Quartette has had some changes. At the death of de Ahna Professor Johann Kruse became second violinist. Three years ago he went to London to assist at the Popular Concerts and to teach there. His place was taken by Carl Halir. Among the celebrated pupils of Joachim may be mentioned Kark, Courvoirsier [sic], Karl Halir (in Berlin), Gustav Hollaender, at the head of the Stern Conservatory, Berlin; Henrich Jacobson, the teacher of Maude Powell and Lilian Shattuck; Johan Kruse, formerly- a distinguished teacher at the Royal High School ; Heinrich Petre, the eminent Dresden teacher; Professor Hubay, Budapest; Paul Listemann, Chicago; Carl Markees, Berlin; Marsick, the eminent Paris teacher; Professor Nachez, London; Theodore Spiering, Chicago. His greatest lady pupils have been Marie Soldat-Roger, Gabrielle Wietrowitz, Leonora Jackson, Geraldine Morgan, Nora Clentsch, Maude Powell and Dora Becker.

54

Professor Joachim has thirteen degrees and marks of distinction. Cambridge University has given him a degree, and I suppose Harvard would have imitated Cambridge if the artist had ever visited America. I do not claim that Joseph Joachim is the greatest living violinist. That were hazardous. He is the greatest living exponent of the severely classical school. He does not live a narrow life musically. He plays only what is great to him. He has played with Lady Halle in England. He has met great artists of all schools. His pupils have never been disloyal to him, although some have studied later with Marsick, Ysaye and others. For Leopold Auer in Russia he has had a sincere respect. Other violinists have not found him cold and pedantic. He has won their respect. There are comments and criticisms which might be made upon the Joachim school. This is not the place for such criticisms. I have found no freer system of bowing, no more beautiful and sincere veneration for the classics, no higher ideals anywhere in the world than in that center of the violin world, Berlin. At the same time it takes a brave heart, a strong body and an elastic temperament to study and wait for the time when you, too, shall sit at the feet of Joachim and reap the reward of your efforts to become one of his pupils.