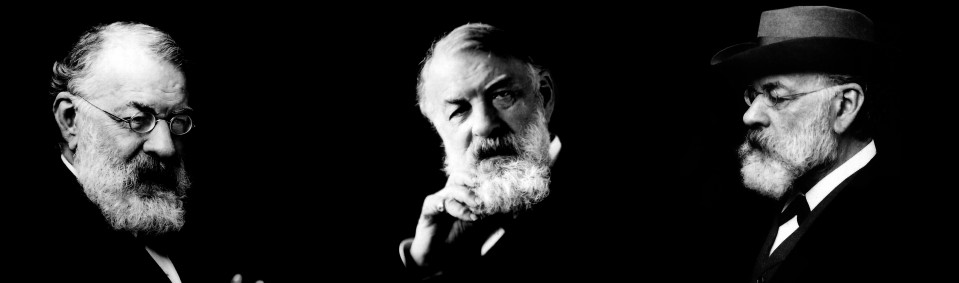

Carl Reinecke, “Persönliche Erinnerungen an Joseph Joachim,” Deutsche Revue 34, no. 4 (1909): 91–95.

English translation below (c) Robert Whitehouse Eshbach 2025

Persönliche Erinnerungen an Joseph Joachim

Von

Karl Reinecke

Am Abend des 16. November 1843 schritt ich den kurzen Weg von meiner Wohnung zum alten Gewandhause in Leipzig; es war für mich ein bedeutsamer Weg, denn an dieser altberühmten Stätte, wo von Mozart an fast jeder große Künstler gespielt und wo Mendelssohn sieben Jahre mit heiligem Eifer seines Amtes als Kapellmeister gewaltet hatte, sollte ich mich nun als berufener Künstler ausweisen. Ein Solistenzimmer gab es in diesen geheiligten, aber äußerlich so bescheidenen Räumen nicht, und bis ich an den Flügel gerufen wurde, hätte ich den Klängen der vorangehenden Nummern durch die Tür lauschen müssen, wenn es mir nicht gelungen wäre, mich in einem Winkelchen

92

auf dem Podium zu verstecken. Eine Sinfonie von Haydn und eine Arie aus dessen „Schöpfung“ waren verrauscht, und nun trat ein zwölfjähriger Knabe im Jäckchen und mit umgeschlagenen Hemdkragen auf und trug die seinerzit berühmte Othellophantasie von Ernst mit vollendeter Virtuosität und mit knabenhafter Unbefangenheit vor. Es war Joseph Joachim, dem am Schlusse das sonst etwas reservierte Gewandhauspublikum stürmisch zujubelte. Ich hatte noch eine ganze Weile zu warten, bis ich mich an den Flügel setzen mußte, um Mendelssohns Serenade und Allegro giojoso zu spielen. Daß das Publikum meine Leistung zwar freundlich aufnahm, mir aber nicht in einer Weise zujubelte wie dem zwölfjährigen Wunderknaben, kränkte mich nicht, denn ich war verständig genug, um es als selbstverständlich zu erachten, daß das Publikum einen Knaben, der auf seiner Geige das ganze Feuerwerk eines brillanten Virtuosenstückes hatte aufblitzen lassen, enthusiastischer entließ als einen neunzehnjährigen befrackten Jüngling, der die liebenswürdige, aber keineswegs bravourmäßig ausgestattete Serenade von Mendelssohn vorgetragen hatte. Von diesem Tage an, da wir beide unser Debüt im Gewandhaussaale ablegten, bis zu Joachims Tode sind wir beide stets in treuer Freundschaft verbunden geblieben. Am Abend des 16. November 1843 hätte keiner von uns ahnen können, daß der eine bis an sein hohes Alter fast alljährlich ein jubelnd bewillkommter Gast im Gewandhause sein würde, der andere aber fünfunddreißig Jahre lang als Kapellmeister dieses Konzertinstituts fungieren und dreiundsechzig Jahre später bei der Feier von Mozarts hundertfünfzigstem Geburtstage ein Konzert dieses Meisters in den Prachträumen des neuen Gewandhauses spielen würde.

Joachim war das siebente Kind jüdischer Eltern, die in einem kleinen Orte in der Nähe von Preßburg lebten. Ohne musikalisches Talent von Vater oder Mutter ererbt zu haben, zeigte sich ein solches dennoch sehr früh, und schon mit sieben Jahren trat der kleine Mann im Adelssaale in Pest als Geiger auf; infolgedessen hatte er das Glück, aufs Konservatorium in Wien gebracht zu werden, woselbst ihm der Vorzug zuteil ward, den Unterricht des berühmten Geigenmeisters Joseph Böhm zu genießen, der ihn zu dem machte, der als Dreizehnjähriger schon einen Mendelssohn imponieren konnte. Mit rührender Dankbarkeit hing er an seinem Lehrer und widmete ihm auch sein Opus 1 Andantino und Allegro scherzoso für Violine mit Orchester. Eine sehr schwierige, vierunddreißig Takte umfassende Kadenz zu diesem Werke schrieb er mir in mein Album mit der Unterschrift: „Meinem lieben hochgeschätzten Freunde C. Reinecke zur Erinnerung an Jos. Joachim.“ Wie die Schrift noch den Knaben verrät, so hatte er auch nach knabenhafter Weise vergessen, das Datum hinzuzufügen; es wird aus dem Jahre 1844 stammen, und zwischen diesem, seinem ersten und seinem letzten an mich gerichteten Schriftstück, dem Glückwunsch zu meinem achtzigsten Geburtstage, welchen er am 23. Juni 1904 namens der Königlichen Akademie der Künste an mich richtete, mögen wohl rund sechzig Jahre liegen.

Ganz naturgemäß stak Joachim bei seinem Erscheinen in Leipzig noch ganz

93

im Banne der Virtuosität, aber durch den steten Umgang mit Mendelssohn, der den Knaben wie ein Vater liebte und förderte, ward er gar bald ins Heiligtum der Kunst eingeführt, und fortan verwendete er seine Virtuosität lediglich zur vollendeten Wiedergabe wahrhaftiger Kunstwerke der Geigenliteratur. Im Jahre 1853 spielte er auf dem Niederrheinischen Musikfeste zu Düsseldorf, und ich hatte zufällig das Glück, diesem seinem ersten Auftreten in den Rheinlanden beiwohnen zu können. Welch ein Andrer, Größerer war er inzwischen geworden. Einst Diener der Virtuosität, jetzt Priester der Kunst. Er spielte das Beethovensche Violinkonzert, das bis dahin unerreichte, welches von dem Augenblicke an, da Joachim es sich zu eigen gemacht hatte, erst in seiner ganzen Größe erkannt worden ist. Wie ein jugendlicher Held, vornehm, aber anspruchslos, erschien er auf dem Podium; kaum jedoch hatte er die ersten, gleichsam verklärten Anfangstakte des Solo gespielt, so sprang ihm infolge der tropischen Hitze, die in der Konzertsaale herrschte, die Quinte, doch rasch entschlossen nahm er dem Konzertmeister Theodor Pixis dessen Geige aus der Hand und spielte, als ob nichts vorgefallen wäre, den ganzen Satz auf der fremden Geige zu Ende. Es ist ein müßiges Beginnen, solch vollendetes Spiel mit Worten zu beschreiben. Aber noch heute, nach sechsundfünfzig Jahren, erinnere ich mich deutlich, daß ich nach diesem Vortrage mich in die einsamen Gänge des Hofgartens schlich, um ungestört den gehabten Kunstgenuß noch einmal in meinem Innern zu durchleben. — In demselben Jahre gab ich mit Joachim ein Konzert in Bremen, in welchem wir u. a. die Kreutzer‑Sonate von Beethoven und das reizvolle H‑Moll‑Rondo von Franz Schubert spielten. Als wir am andern Morgen allein im Eisenbahncoupé saßen, trieben wir allerlei musikalische Allotria, gaben uns Scharaden auf und improvisierten zweistimmige Kanons u. s. w., da sah ich plötzlich auf der Fußmatte etwas Goldiges blinken und rief: „Schau her, Joachim, da liegt ein Louisd’or!“ Er war ebenso erstaunt über diesen Fund wie ich, ward aber ganz verblüfft, als wir nach und nach mehr von diesen angenehmen Goldstücken fanden. Da ging ihm plötzlich ein Licht auf: er hatte seinen Anteil an der Konzerteinnahme blank in seine Hosentasche gesteckt, und diese hatte ein Loch. —

Joachim, welcher bis dahin nur vorübergehend und auf kurze Zeit feste Stellungen eingenommen hatte (so als Lehrer des Violinspiels am Konservatorium in Leipzig und als Konzertmeister in Weimar), nahm im Jahre 1853 die Berufung des Königs Georg V. von Hannover an, welcher ihn zu seinem Kammervirtuosen und zum Königlichen Konzertmeister ernannt hatte. In dieser Stellung verblieb er bis zum Jahre 1866. Im Jahre 1863, kurz nachdem er sich mit der trefflichen Sängerin Amalie Weiß vermählt hatte, lud er mich ein, in einem von ihm geleiteten Abonnementskonzert meine Ouvertüre zu Calderons „Dame Kobold“ zu dirigieren und bei dieser Gelegenheit sein Gast in seinem neuen Heim zu sein. Es ist mir eine liebe Erinnerung, Zeuge gewesen zu sein von dem jungen Glück dieses herrlichen Künstlerpaares. — Ein eigentümlicher Zufall ist es, daß die Zahl „3“ eine solche Rolle in meinen markantesten Begegnungen mit Joachim spielt: Unser erstes Begegnen war im Jahre 1843, zehn

94

Jahre später gab ich mit ihm das Konzert in Bremen, abermals nach zehn Jahren trat ich, wie soeben erzählt, in seinem Konzert als Komponist und Dirigent auf, und im Jahre 1873 spielten wir miteinander die H‑Moll‑Sonate von Joh. Seb. Bach in einem Konzerte in Leipzig, welches von den Freunden und Verehrern des Niederkomponisten Robert Franz veranstaltet wurde, um dem durch Ohren‑ und Handleiden schwer geprüften Künstler eine Ehrengabe überreichen zu können. Im Jahre 1883 hatte ich zum erstenmal die Freude, Joachim als Quartettspieler mit seinen trefflichen Genossen de Ahna, Wirth und Hausmann begrüßen zu können. Am 23. April fand diese Quartettsoiree im Saale des Gewandhauses vor einem erwartungsvoll gespannten Hörerkreise statt. Zwar hatte ich meinen Freund gar manches Mal schon als Quartettspieler bewundert, aber niemals als Haupt des von ihm in Berlin gebildeten Quartetts, einer Korona von Künstlern ersten Ranges, die sich nun bereits seit Jahren so ineinander eingelebt hatten, daß nirgends eine Schwäche, nirgends ein Hervordrängen des einzelnen zu entdecken war, und daß selbst die improvisierte Nuance, die sich irgendeiner gestattete, sofort von den übrigen erfaßt wurde, als wäre sie in den Proben vorbereitet worden. Mir war es mit Erfolg gelungen, diese illustre Vereinigung zu einem Besuche Leipzigs zu veranlassen, und ich hatte die Freude, daß das Leipziger Publikum den vollendeten Leistungen volles Verständnis entgegenbrachte. Man begegnet manchem großen Virtuosen, der da scheitert, wenn er Meisterwerke der Kammermusik zur Erscheinung bringen soll, weil ihm das Verständnis für diese edelste aller Kunstgattungen abgeht, aber Joachim, der in allen Sätteln gerechte Musiker von sicherstem Stilgefühl und feinstem Empfinden, wußte mit seinen Kunstgenossen ebenso hinreißend ein sonnig‑heiteres Quartett von Haydn wie das tiefsinnige der Beethoven’schen Muse zu interpretieren, ebenso wohl den romantischen Zauber in Schumanns oder Schuberts Schöpfungen zur Geltung zu bringen wie die schlichte Größe und deutsche Anmut eines Mozart. Und abermals zehn Jahre später traf ich mit Joachim am Rhein zu gemeinschaftlichem Musizieren zusammen. Am 2. Februar 1889 hatte die „Bonner Zeitung“ folgende kurze Notiz gebracht: „Das Haus Bonngasse Nr. 20 — Beethoven’s Geburtshaus — ist für den Preis von 57 000 Mark von dem jetzigen Besitzer an Herrn … hierselbst verkauft worden.“ Es hatten sich nämlich kurz zuvor kunstbegeisterte Männer von Bonn vereinigt, um dieses denkwürdige Haus, in dem der größte Sohn dieser Stadt das Licht der Welt erblickt hatte, zu erwerben und der Nachwelt als ein Denkmal pietätvoller Dankbarkeit zu erhalten. So entstand der Verein „Beethoven‑Haus“ zu Bonn. Um die nötigen Mittel zur Durchführung dieses Unternehmens zu beschaffen, entschloß man sich zur Veranstaltung periodisch wiederkehrender Kammermusikfeste großen Stiles mit mustergültigen Aufführungen. Das erste dieser Feste fand deshalb im Jahre 1890 vom 11. bis 15. Mai statt. Joachim war zum Ehrenpräsidenten des Vereins ernannt worden, und sein Quartett war natürlich eine Hauptattraktion. Leider war de Ahna inzwischen von hinnen geschieden, jedoch durch

95

einen Schüler Joachims aufs beste ersetzt worden. Auf diesem Feste trug ich u. a. mit Joachim und Alfred Piatti Beethovens Trio Op. 70 Nr. 2 vor. Als wir drei später photographiert wurden, addierten wir unsre Lebensjahre und gewannen die stattliche Zahl von 193. Das zweite Fest ward im Jahre 1893 vom 10. bis 14. Mai gefeiert, und kam die Zahl „3“ wieder einmal zu ihrem Rechte, denn ich hatte wiederum mit Joachim ein großes Trio von Beethoven zu spielen.

In Kürze sei schließlich noch der beiden Feiern gedacht, die bei der Enthüllung der Denkmäler für Mendelssohn in Leipzig und für Schumann in Zwickau stattfanden. Am 26. Mai 1892 ward das erzene Standbild Mendelssohns enthüllt und gipfelte die Feier in einem Festkonzerte im neuen Gewandhause, welches ich leitete und in dem Joachim das Mendelssohnsche Violinkonzert spielte, während wir beide uns am Vorabend bei einer mehr intimen Feier bei der Ausführung Mendelssohnscher Kammermusikwerke beteiligten. Die Enthüllung des Schumannmonumentes ward mit einem mehrtägigen Musikfeste gefeiert, und zwar Juni 1901. Joachim und ich, als die einzigen noch lebenden Künstler, die Schumann nahegestanden hatten, waren eingeladen, das Fest im Verein mit dem einheimischen Musikdirektor zu leiten und desgleichen uns als Ausführende daran zu beteiligen. Als Joachim unter meiner Führung des Orchesters die Geigenphantasie des Meisters vortrug und plötzlich vor übergroßer Rührung den Faden verlor, ward es auch mir weh ums Herz, und es war wohl zu verstehen, wenn wir uns nach Beendigung des Stückes in den Armen lagen, des so trübe dahingeschiedenen, von uns so geliebten Meisters gedenkend. Das war mein letztes Zusammensein mit Joachim.

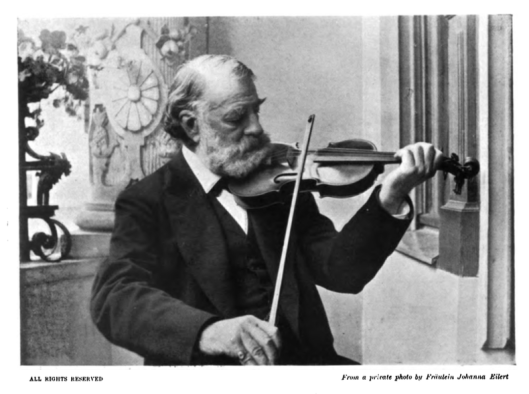

Nun ist auch er, der große Geigenmeister, heimgegangen. Die jüngere Generation, die ihn nur in seinen letzten Lebensjahren geigen hörte, behauptete, oft enttäuscht zu sein, weil sie wohl die Schwächen bemerkte, die durch die gealterten Glieder bedingt waren, nicht aber die Größe seines Stils und die einfache Schönheit seines Vortrages zu würdigen wußte. Man mag es bedauern, daß Verhältnisse ihn zwangen, noch bis kurz vor seinem Ende öffentlich aufzutreten; aber es fällt darum doch kein Blättchen aus dem immergrünen Lorbeer, der seine edle Stirn umwindet.

Personal Memories of Joseph Joachim

by Carl Reinecke

On the evening of 16 November 1843 I walked the short way from my lodgings to the old Gewandhaus in Leipzig; it was a significant path for me, for in that time‑honored place, where from Mozart onward almost every great artist had played and where Mendelssohn had, with sacred zeal, discharged the post of Kapellmeister for seven years, I was now to present myself as a fully fledged artist. There was no soloist’s room in those hallowed but outwardly so modest quarters, and until I was called to the piano I would have had to listen through the door to the sounds of the preceding numbers, had I not succeeded in hiding myself in a little corner on the platform. A symphony by Haydn and an aria from his “Creation” had died away, and now a twelve‑year‑old boy appeared in a little jacket and with turned‑down shirt collar and played Ernst’s then famous Othello Fantasy with consummate virtuosity and boyish self‑possession. It was Joseph Joachim, to whom, at the end, the otherwise somewhat reserved Gewandhaus audience gave stormy applause. I still had quite a while to wait before sitting down at the piano to play Mendelssohn’s Serenade and Allegro giojoso. That the audience received my performance kindly, but did not cheer me in the same way as the twelve‑year‑old child prodigy, did not hurt me, for I was sensible enough to regard it as self‑evident that the audience would greet with greater enthusiasm a boy who had made the entire fireworks of a brilliant virtuoso piece flash from his violin than a nineteen‑year‑old, properly tail‑coated youth who had played Mendelssohn’s amiable but by no means bravura‑like Serenade. From that day on, when we both made our debuts in the Gewandhaus hall, down to Joachim’s death we remained united in faithful friendship. On the evening of 16 November 1843 neither of us could have guessed that the one would, almost every year until his old age, be a joyfully welcomed guest in the Gewandhaus, while the other would serve for thirty‑five years as Kapellmeister of this concert institution and, sixty‑three years later, would conduct a concert of this master in the splendid rooms of the new Gewandhaus in celebration of Mozart’s one hundred and fiftieth birthday.

Joachim was the seventh child of Jewish parents who lived in a small town near Pressburg. Although he had inherited no musical talent from either father or mother, such a gift nevertheless revealed itself very early, and already at the age of seven the little fellow appeared as a violinist in the Adelskasino in Pest; in consequence he had the good fortune to be taken to the Conservatory in Vienna, where he had the privilege of receiving instruction from the famous violinist Joseph Böhm, who made him into someone who, already at thirteen, could impress a Mendelssohn. With touching gratitude, he clung to his teacher and dedicated to him his Opus 1, Andantino and Allegro scherzoso for violin and orchestra. He wrote a very difficult cadenza of thirty‑four bars to this work in my album with the inscription: “To my dear and highly esteemed friend C. Reinecke in memory of Jos. Joachim.” As the handwriting still reveals the boy, so he had also, in boyish fashion, forgotten to add the date; it must be from the year 1844, and between this, his first letter to me, and his last written communication to me, the congratulatory note on my eightieth birthday, which he addressed to me on 23 June 1904 in the name of the Royal Academy of Arts, there lie roughly sixty years.

Quite naturally, when Joachim made his appearance in Leipzig he was still entirely under the spell of virtuosity, but through his constant association with Mendelssohn, who loved and encouraged the boy like a father, he was soon introduced into the most sacred realm of art, and from then on he used his virtuosity solely for the perfect realization of genuinely artistic works of the violin literature. In 1853 he played at the Lower Rhine Music Festival in Düsseldorf, his first appearance in the Rhineland, which, quite by chance, I had the good fortune to be able to attend. What a different, greater man he had become in the meantime. Formerly a servant of virtuosity, now a priest of art. He played Beethoven’s violin concerto, that until then unsurpassed work which was first recognized in its full greatness from the moment Joachim made it his own. Like a youthful hero, noble yet unassuming, he appeared on the platform; but scarcely had he played the first, as it were transfigured, opening bars of the solo when, owing to the tropical heat that prevailed in the concert hall, the E string snapped; yet he quickly and resolutely took the concertmaster Theodor Pixis’s violin from his hand and, as if nothing had happened, played the entire movement to the end on the unfamiliar instrument. It is a futile undertaking to try to describe such perfect playing in words. But even today, fifty‑six years later, I remember clearly how, after this performance, I slipped into the solitary paths of the Hofgarten in order, undisturbed, to relive within myself the artistic enjoyment I had received. That same year I gave a concert with Joachim in Bremen, in which we played, among other things, Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata and Schubert’s delightful rondo in B minor. The next morning, when we were alone together in a railway compartment, we indulged in all kinds of musical horseplay, set each other charades and improvised two‑part canons and so on, when I suddenly saw something golden gleam on the floor‑mat and cried: “Look, Joachim, there lies a louis d’or!” He was as astonished at this find as I was, but became quite dismayed when we gradually discovered more of these pleasant gold pieces. Then suddenly a light dawned on him: he had put his share of the concert takings loose into his trouser pocket, and it had a hole.

Joachim, who until then had held only temporary and short‑term posts (for example as teacher of violin playing at the Conservatory in Leipzig and as concertmaster in Weimar), accepted in 1853 the appointment of King George V of Hanover, who had named him his chamber virtuoso and royal concertmaster. He remained in this position until 1866. In 1863, shortly after he had married the excellent singer Amalie Weiß, he invited me to conduct, in a subscription concert directed by him, my overture in C major to Calderon’s “Dame Kobold,” and on this occasion to be his guest in his new home. It is a dear memory for me to have been witness to the youthful happiness of this splendid artist couple. A peculiar coincidence is that the number “3” plays such a role in my most striking encounters with Joachim: our first meeting was in 1843; ten years later I gave the concert in Bremen with him; another ten years later, as just related, I appeared in his concert as composer and conductor, and in 1873 we played together Bach’s B minor sonata in a concert in Leipzig which was organized by the friends and admirers of the now‑deceased composer Robert Franz in order to present the artist, heavily afflicted with ear and hand ailments, with a token of honor. In 1883 I had for the first time the pleasure of welcoming Joachim as quartet player together with his excellent colleagues de Ahna, Wirth, and Hausmann. On 23 April this quartet soirée took place in the hall of the Gewandhaus before a circle of listeners tense with expectation. I had indeed admired my friend many a time as quartet player, but never as the head of the quartet he had formed in Berlin, a crown of artists of the first rank, who had grown so intimate with one another over the years that no weakness, no pushing of any individual was to be detected, and even the improvised nuance that any one of them permitted himself was immediately grasped by the others as if it had been prepared in rehearsal. I had succeeded in persuading this illustrious ensemble to visit Leipzig, and it gave me joy that the Leipzig public responded to their perfect performances with complete understanding. One meets many a great virtuoso who fails when he is called upon to present masterpieces of chamber music, because he lacks the understanding for this noblest of all art forms; but Joachim, a musician sure‑seated in every saddle, of the most reliable sense of style and the finest feeling, knew how, together with his artistic comrades, to interpret as irresistibly a sunny, cheerful quartet by Haydn as the profound creations of Beethoven’s muse, and equally to bring to life the romantic magic of Schumann’s or Schubert’s works and the simple greatness and German grace of a Mozart.

And yet another ten years later I met Joachim again on the Rhine for joint music‑making. On 2 February 1889 the Bonner Zeitung carried the following brief notice: “The house Bonngasse No. 20 — Beethoven’s birthplace — has been sold by its present owner to Mr. … of this city for the price of 57,000 marks.” Not long before, art‑loving men of Bonn had joined forces to acquire this memorable house, in which the greatest son of that city had first seen the light of the world, and to preserve it for posterity as a monument of reverent gratitude. Thus the “Beethoven‑Haus” association in Bonn came into being. To procure the necessary funds for carrying out this enterprise, it was decided to organize periodically recurring chamber‑music festivals on a large scale with exemplary performances. The first of these festivals therefore took place in 1890 from 11 to 15 May. Joachim had been appointed honorary president of the association, and his quartet was naturally one of the chief attractions. Unfortunately, de Ahna had meanwhile passed away, but he was admirably replaced by one of Joachim’s pupils. At this festival I played, among other things, Beethoven’s Trio Op. 70 No. 2 with Joachim and Alfred Piatti. When the three of us were later photographed, we added together our ages and arrived at the imposing sum of 193. The second festival was held in 1893 from 10 to 14 May, and once again the number “3” came into its own, for again I had to play a large Beethoven trio with Joachim.

Finally, mention should be made of the two celebrations at which the monuments to Mendelssohn in Leipzig and to Schumann in Zwickau were unveiled. On 26 May 1892 the bronze statue of Mendelssohn was revealed, and the celebration culminated in a gala concert in the new Gewandhaus, which I conducted and in which Joachim played Mendelssohn’s violin concerto, while on the previous evening we both had taken part in a more intimate gathering devoted to Mendelssohn’s chamber music. The unveiling of the Schumann monument was celebrated with a multi‑day music festival in June 1901. Joachim and I, as the only surviving artists who had been close to Schumann, were invited to direct the festival together with the local music director, and likewise to take part as performers. When Joachim, under my direction of the orchestra, performed the master’s violin fantasy and suddenly, from overwhelming emotion, lost the thread, it tore at my heart as well, and it was only natural that, at the end of the piece, we should fall into each other’s arms, thinking of the so sadly departed master whom we had loved so much. That was my last time together with Joachim.

Now he too, the great master of the violin, has gone home. The younger generation, who heard him play only in the last years of his life, often claimed to be disappointed, because they noticed the weaknesses due to his aging limbs but did not know how to appreciate the greatness of his style and the simple beauty of his delivery. One may regret that circumstances forced him to appear in public until shortly before his end; but not a single leaf falls on that account from the evergreen laurel that encircles his noble brow.