The Living Age, Seventh Series, Vol. 36 (July, August, September 1907), pp. 693-695

__________

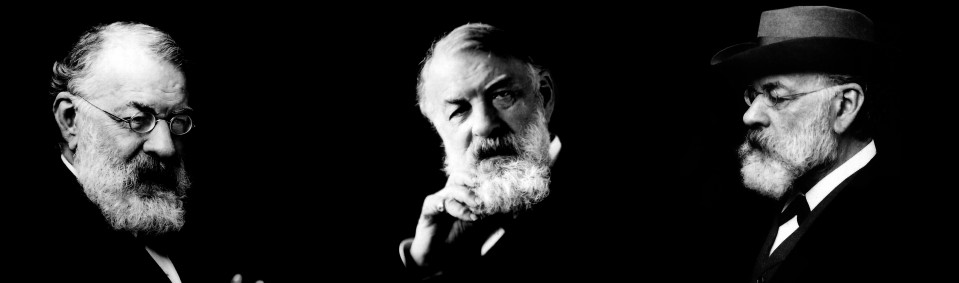

JOSEPH JOACHIM. — A REMEMBRANCE

Edith Sichel

“Coleridge is dead!” Charles Lamb would suddenly exclaim in the midst of other conversation, during the weeks that followed the poet’s death. And those who have loved Joseph Joachim feel the need of repeating such words to make them realize that he has gone. When men have lived the life of art or goodness belonging more or less to the eternal order of things, it is more difficult to grasp their mortality. For those who care for beauty, for the best in music and in life, a link has snapped never to be replaced. Music is not dead, cannot die; but the interpreter-genius who revealed it in its purest depths has passed away.

Those who, but a few years ago, heard him still at his strongest (at his best he always was) know the utmost limit of human achievement in art. “Whether in the body, or out of the body, I know not,” was the feeling with which one always came away from hearing him. What was it that made his playing what it was? Was it his tone, his phrasing, the might and grace of his rhythm? Was it the wonderful union of passion and restraint? It was all these, it was something more than these. He had not drunk at the spring of inspiration, he was that spring himself. It was this fount within him which compelled him, in spite of his vital personality, to become the music that he played; to be, in turn, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms. Perhaps it is the heritage of his race to be the selfless testifier that he was. “If people would only trust the music,” he once said, “they too often put themselves into it.” Once when Brahms heard Joachim play again after an interval, “I felt,” he wrote, “that there had been something lacking in life. Oh, how he plays!”

This particular effect of his music was due not only to the musician; it came from the man. If he stands for art he also stands for goodness: for duty, for loyalty, for obedience. Not for virtue, which affects a man’s relation to himself, but for the kinder, sweeter power which means his bond with others; the “human charity,” which Beethoven said “was the only superiority that counted.” Sometimes one was even tempted to wish that Joachim’s charity did not suffer so long and be kind. The most social of men, he would not reject anybody.

Of course, like all interesting people,

694

he liked interesting people best, and men who had made their mark in the world inspired him with respect and curiosity. He was courtly without being a courtier. His feeling for the Emperor, for Royalty, was a sentiment — the sentiment that Goethe had at Weimar. Bismarck was one of the persons for intercourse with whom he had cared most, and for the last sixty years he had known most people worth knowing both in Germany and England. In the ‘fifties he had played to Goethe’s Bettina, and in his drawing-room at Berlin there hung a water-color sketch of him and a quartette of that day, high-collared in swallow-tailed coats, playing to a little old lady, Bettina von Arnim.

Carl Johann Arnold: Quartettabend bei Bettina

But the great friendships of his life were those for Mendelssohn, the Schumanns, and Brahms. His relations with Schumann began when he was very young. He had been playing Beethoven’s Concerto, and he and Schumann came out together from the hot, crowded concert-room into the star-lit open. “Little Master Joachim,” said Schumann, looking skywards, “do you think that star knows that you have just played the Beethoven Concerto and that I am sitting by you here?” As he spoke, he laid a hand tenderly upon the boy’s knee. The incident was always alive to Joachim as if it had been yesterday. Fifty years afterwards he loved to tell the story, in his vivid way, acting the gesture, recalling the tones which the years had not dulled for him. Joachim’s friendship for Brahms was one of those rare comings together which influence the history of art, like the friendship of Goethe and Schiller, of Coleridge and Wordsworth. In some ways the meeting of these two meant more than the conjunctions of creators, for without Joachim it is difficult to conceive how Brahms would have been adequately revealed to the world. Joachim immediately recognized in him a sovereign of the legitimate dynasty. He himself had no mean place in the company of great composers, but, humbly putting his creative work aside, he devoted himself to the reverent interpretation of the greater masters, more especially of this last one, whom the world as yet did not understand. It was England that he found the most responsive, and he reaped his reward. After forty-five years, his last pleasure in this country was to lead a performance of all Brahms’ chamber-music and to witness its established success.

The difference between Joachim and other artists was that intellectual equals such as these did not spoil him for the less effectual myrmidons. But with all his kindness it would be misleading to write of him as if he were a saintly bishop, instead of the most human of human beings. He did not affect tame company; he loved good looks, he loved quick wits and brilliance. He was himself witty. His humor had a sly malice, an innocent finesse, and he did not object on occasions to point it at particular persons. Some one had been criticising Mr. Z., a fussy man of his acquaintance. “But he is such a kind friend,” he rejoined — then, as if by an after-thought — “and he always lets me know it.”

Another time, at a concert of Bach’s music, he was sitting next a lady of high rank; they were looking over the score together. “She pointed out the beauties that were there — and some beauties that were not there,” he remarked afterwards. But his vision of their weaknesses did not at all interfere with his liking either for Mr. Z. or the lady. His satire was never discourteous. He was asked if a woman of note — a reputed liar — were untruthful, as was supposed. “Let us call it romantic,” he answered; “she was a very attractive person.” The difficulty in defining Joachim, the most unpara-

695

doxical of persons, is to bring home to those who did not know him the union in him of simplicity and subtlety, of dignity and spontaneity, of a warmth that thrilled its recipient with a dislike of extravagance and excess; to make men realize the fulness of his artist’s temperament, together with the qualities least supposed to belong to an artist. Joachim’s punctiliousness, his self-control, his good manners, his good sense, his distaste for what was not obvious, his still greater distaste for what was lawless, are not the attributes usually pertaining to the popular idea of a genius.

We have said that he gave up composition. It was not only to interpret the work of others that he did so. It was to fulfil his mission as a teacher. Those who have had the memorable good fortune to watch him among his pupils at his Hochschule, to see him conduct his orchestra, a king whose kingdom was youth; those who have witnessed his patience with all who did their best, his wrath with what was lazy or slovenly, understand how he spent himself for them. Of his sovereign kindness to young musicians, there are many stories to tell. He loved young life; he exacted nothing from it. “Am I boring you, children?” he asked some girls a little time ago, while he was playing Mozart.

Not only among his scholars was Joachim a King. There is a picture of him fresh before my eyes, when once, after a festival at Bonn, he was returning from a Festfahrt on the Rhine. As he stepped off the boat, a crowd received him, and he passed up to the town between two files of cheering people; undergraduates, tradesmen, Herr Doktors, English pilgrims, friends of all sorts. He had not expected an ovation; he was moved almost to tears as he walked between the ranks with royal simplicity; and

Blessings and prayers, a nobler retinue

Than sceptered king or laurelled conqueror knows,

Followed this wondrous potentate

Yet the most enduring image of him, the one which lives for ever in our hearts, is the image of Joachim the player, standing by himself, or sitting with his Quartet, his Jovian head straight to the audience. The massive hair, the watchful eyes, the wonderful square, supple hands, from which virtue went forth, complete the man. He is surrounded by an atmosphere of concentration. His face wears a look of tension, a patient, almost troubled expression. Then the mighty bow is upraised, the Olympian fiddle poised against the shoulder, and the first attack holds us breathless. The tension disappears from his countenance; it becomes calm with a victorious serenity, with a rare intellectual force. There is no exaltation, no throwing back of the head, no common sigh of emotion, or excitement. But the eyes are transfigured with a spiritual light; the face is pervaded by an intense reverence.

The impression belongs to many places: to the Ducal Schloss at Meiningen amidst the green Thuringian hills; to the hall in the humble Yorkshire village at whose festival, amongst the moors, he liked to play; to the grim smoking towns of the Black Country; most familiarly to St. James’s Hall, where he reigned so long.

Once at the rehearsal of a concert in that little Yorkshire village, he was sitting deep in talk with a friend. The last singer had finished her performance, but he did not perceive it. He looked up, and discovered that he was waited for. “It is my turn now; I must go,” he said, concerned, almost as if he were a child hastening to obey his master’s call. His turn has come now — the call found him ready.

Edith Sichel.

__________

Excerpted from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

Sichel, Edith Helen (1862–1914), historian and philanthropist, was born on 13 December 1862 at 25 Princes Gardens, London, the daughter of Michael Sichel (1819–1884), a cotton merchant, and his wife, Helena Reiss (1833–1888); her parents were Christians, but of German Jewish descent. She was well educated, becoming proficient in French, German, and Latin. In 1876 she met and formed a close friendship with Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1861–1907), with whom she went to read Greek classics with William Johnson Cory (1823–1892), the poet and former master at Eton. She also attended Professor John Wesley Hales’s lectures on Elizabethan and Jacobean drama in 1880.

At the age of twenty-three Edith Sichel joined the Whitechapel branch of the Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants. Through her work here she met Canon Samuel Barnett and his wife Henrietta, and also Emily Ritchie, who became her closest friend. Her philanthropy, informed by her deep Christian faith, was essentially conservative and individualistic: accepting as God-given the class system of Victorian society, she held that the core of her mission was the creation and development of personal friendships, and had little interest in administrative and committee work which resulted from the growth of institutional social work.

Sichel’s faith in personal initiative in philanthropic work was evidenced by her private projects, pursued after bad health had forced her to abandon her work in the East End in 1891. In 1889 she and Emily Ritchie established a nursery for East End workhouse children in Chiddingfold near Witley, where they were renting a cottage. When they moved to The Hurst, Hambledon, in 1891 they started a home for Whitechapel girls, where they intended to train them for domestic service.

However, Edith Sichel’s leading interest from the 1890s was her literary career. Her first published work, the tale of a Wapping girl entitled ‘Jenny’, which appeared in the Cornhill Magazine in 1887, was inspired by her East End work. She became a steady contributor to journals and magazines, including The Pilot, the Monthly Review, the Times Literary Supplement, and the Quarterly Review, revealing herself to be an enthusiastic, perceptive, and generous reviewer of histories, biographies, and memoirs. In 1893 she published Worthington Junior, an undistinguished novel, before turning to the more congenial pursuit of French history. The Story of Two Salons (1895) described the salons of the Suards and Pauline de Beaumont, while The Household of the Lafayettes (1897) dealt with the pre- and post-Revolution history of a prominent French family. In 1903, with G. W. E. Russell, she published Mr Woodhouse’s Correspondence, a collection of comic correspondence (which had originally appeared in The Pilot) between the family and associates of the imaginary Algernon Wentworth-Woodhouse, a rich, miserly, and valetudinarian egotist. This was followed in 1906 by The Life and Letters of Alfred Ainger, a tribute to a close friend. Another such tribute appeared in 1910, when she contributed a memoir to Gathered Leaves, a posthumous collection of pieces by Mary Coleridge, whose death in 1907 was a considerable blow. Women and Men of the French Renaissance (1901) foreshadowed more directly her magnum opus, a two-volume account of the life and career of Catherine de’ Medici, published as Catherine de’Medici and the French Reformation (1905) and The Later Years of Catherine de’Medici (1908). The Renaissance, written for H. A. L. Fisher’s Home University Library of Modern Knowledge series, and Michel de Montaigne, both published in 1911, were the last of her works to appear in her lifetime. In humorous self-deprecation, Sichel described herself as ‘only a gossiping lady’s maid who curls the hair of History’. In fact her histories were well researched in primary as well as secondary sources, and she believed that a woman historian could have a distinctive and serious role in exploring the more personal and domestic aspects of history. Vivid, impressionistic portraits of many leading figures in French courts and salons bear witness to her appropriately Renaissance belief that history was ‘human life remembered’ (Ritchie, 147, 45).

In 1911 Edith Sichel began to hold classes for female prisoners at Holloway Prison, where her sister was already a visitor. She became deeply interested in the 1914 Prison Reform Bill, drawing up a report for the commissioners of prisons and attending police courts to examine sentencing. This additional work may have contributed to her unexpected death, on the night of 13 August 1914, while visiting friends at Borwick Hall, near Carnforth, Lancashire.

Edith Sichel was remembered by her contemporaries as a woman of great charm, witty, cultivated, and cheerful, with a genius for friendship. Both her books and her letters reveal an attractive and vivacious personality. While her poetry is generally third rate and laboured, her prose is elegant, absorbing, and seasoned with epigrams. Her appearance was striking rather than handsome—photographs show a large-featured, dark-haired woman, a sort of beautified George Eliot—but observers commented on her expressive face, ‘full of mobility, vigour and refinement’ (Cornish, 217).

Rosemary Mitchell