© Robert W. Eshbach, 2013

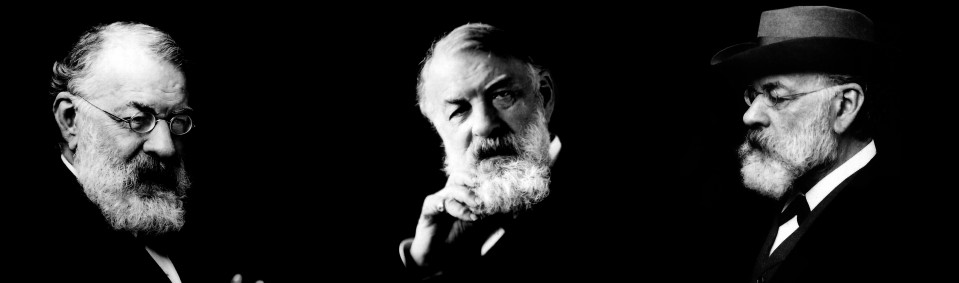

King George V of Hanover

George V, King of Hanover [i]

Georg Friedrich Alexander Karl Ernst August (1819-1878) was the grandson of Great Britain’s King George III, and first cousin to Britain’s Queen Victoria. Until the birth of Victoria’s first child in 1841, he was second in the line of succession to the British throne. Hanoverian kings ruled Britain until Victoria became Queen of England in 1837. At that time, the Lex Salica, which forbade a female succession in Hanover, forced an end to the 123-year old conjoined British-Hanoverian monarchy. Georg, the Crown Prince of Hanover and Prince of Cumberland succeeded his father Karl August as King of Hanover on November 18, 1851, styling himself King George V. When Joachim arrived in Hannover, George had been monarch for little more than a year.

The King was blind. He had lost the sight of one eye due to a childhood illness — the other in a freak circumstance: at the age of fourteen, swinging a purse full of coins, he accidentally hit himself in his good eye.

George was broadly educated, and possessed an impressive memory. He was passionate about music, an appreciation that could only have been enhanced by his blindness. “From early youth on, I have striven with ardent love to make music my own,” he wrote. “For me, she has become an exquisite companion and comforter throughout the course of my life. She became more and more priceless to me, the more I learned to appreciate and understand her immeasurable wealth of ideas and inexhaustible abundance; the more intimately her poetry mingled with my entire being.” [ii]

King George was musically trained. He had studied piano with Ferdinand David’s sister Louise Dulcken, and was the composer of some two hundred works, including songs, choruses, cantatas, piano pieces and a symphony. [iii] As monarch, he involved himself directly in the musical life of his court. “The king was his own general manager,” wrote Georg Fischer, a contemporary chronicler of the Hanoverian musical scene. “He decided on opera repertoire, concert programs and engagements, and distributed new operas among the music directors in a highly personal way. Not seldom, specific operas, symphonies and other concert pieces were undertaken on special orders. The character and the casting of roles was treated with the seriousness of affairs of state.” [iv] One might equally well say that the king treated the court music with the importance that he assigned to religion. “His attitude toward art was idealistic;” Fischer tells us, “he lived in the conviction that artists were subject to a different tribunal before the throne of God.” [v]

This sense of the significance of music had come to him early. At the age of twenty, Crown Prince George lamented: “One so often hears remarks by musical enthusiasts that reveal that they not only fail to recognize the exalted and sublime character of music, they actually have a false idea of it; they regard it as merely a means of ordinary entertainment, like card-playing and dancing, or rather through their remarks show that they deem it to be no more than a pastime.” [vi] Wishing to give fuller expression to his own deeper appreciation of the musical art, he published his Ideas and Observations on the Characteristics of Music (Ideen und Betrachtungen über die Eigenschaften der Musik) in 1839. “If only a few can become deeply permeated with the conviction that this gift of heaven, this speaking witness to revelation, originates from God alone,” he wrote, “if only one can be moved to adopt it in the condign praise of the supreme, then the purpose of these lines is fulfilled.” [vii]

Reactionary in his politics, George V was also traditional in his musical understanding. “Music is a language in tones,” he wrote. But the language he understood was not the language of tones that was the revolutionary intellectual invention of the early romantic thinkers. His understanding was informed by the Enlightenment principle of mimesis—a concept that originated in the visual arts and poetry, and traces its history back to Plato and Aristotle. According to this doctrine, art is deemed good insofar as it successfully imitates nature (in Aristotle, art imitates nature, not as it is, but as it ideally ought to be). Thus, in the eighteenth century, music was said to “paint:” to portray rather than to evoke. The echo of Aristotle’s ideas can be heard in the words of the king: “Ideas, feelings, world events, natural occurrences, paintings, scenes from life of every kind can be clearly and intelligibly expressed through music, as through any language in words.” [viii] It is striking that the examples he cites in his chapter on “Instrumental Music” are distinctly visual in their aspect: the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven, with its scene by the brook, its merry dancing, its sublime thunderstorm, and especially its scene of thanksgiving; the Creation of Haydn, (“How expressive, how true is the music of the “fleeing of the host of infernal spirits, down into eternal night… above all, however, how the composer portrays in the most gripping manner, with all the powers of music, the moment that is evoked with the Creator’s words: ‘let there be light:” “and there was light!”); Weber’s Invitation to the Dance, (“the faithfulness and truth with which all details and small incidents of a ball are portrayed: the invitation of the dancer, the subsequent acceptance of the lady dancer, the dance itself, the conversation in a period of rest, the iteration of the dance, and the leading of the lady dancer back to her seat…”); the overture to Weber’s Freischutz, (“through which the listener receives a kind of overview of the events of the entire compositon.”); and the introduction to Bellini’s Norma, (“…a most skillful portrayal of a locale. Beginning with low tones, it unfolds itself in gloomy harmonies, and gives the very impression that the woodsy darkness of a vast grove brings forth in human feelings… The reader will certainly be even more struck by the felicitousness of this tone-painting, when I cite the comment of a blind person who, listening to this introduction for the first time, immediately guessed the portrayal of a forest-outing at the scene!”). [ix]

The Family of King George V of Hanover [x]

“The King preferred to listen to music in the circle of his family,” wrote pianist and conductor Bernhard Scholz. [xi] “Evenings, Joachim and I were very often called to Herrenhausen [the royal residence]. The King was friendly; the Queen kindliness itself. The royal children were well-behaved and modest. Two nephews of the King and the Princes Colms were among the regular guests; likewise, the lady-in-waiting to the Queen, Fräulein von Gabelentz — a dignified lady — and, in later years, the Swedish voice teacher Lindhult were always present; by turns one of the adjutants on duty, now and then the father of the young Princes Colms, a step-brother of the King. Every year, the old Duke von Altenburg, the father of the Queen, came for a visit, accompanied by his sister, Princess Therese. Two of the King’s brothers-in-law appeared regularly, Grand-Duke Konstantin, brother of Emperor Alexander II, with his beautiful wife — who surpassed even Empress Eugenie with her proud bearing and grace of movement — and the Grand-Duke and Grand-Duchess of Oldenburg. The Grand-Duke [Konstantin], who played ‘cello, was fond of music; the Grand-Duke [of Oldenburg], on the other hand had no interest in it — but did not feign any, and withdrew to an adjacent room to look at copperplate engravings or to read.”

“The King could tolerate unbelievable quantities of music, but he did not possess a reliable judgement,” wrote Scholz; “he liked everything, particularly the pleasantly agreeable, and under this precondition also the good; in this way he was able to gain respect for Joachim’s art. He repeatedly requested certain agreeable pieces, eg. a Barcarolle and a Gavotte of Spohr. I would really like to know how often we played them for him! Then, he would consent to hear one of the Mozart and the easier Beethoven sonatas, or the variations from the Kreutzer sonata. There was no pre-set program; the king chose from the things we brought with us — Joachim well knew what he preferred. After the music, their majesties sat with us for tea and casual conversation, which the king was very good at leading. In the end, one of the ladies-in-waiting, or, when she was present, Princess Therese herself would prepare an excellent Warmbier.” [1] Citing this passage, Beatrix Borchard comments: “Joachim, who had repeatedly stressed that an artist does not exist for the entertainment of others, nevertheless served at the King’s beck and call as a ‘living phonograph record.’” [xii]

Georg V Hannover: Ideen und Betrachtungen über die Eigenschaften der Musik

See also: Georg V Hannover: Musik und Gesang

[1] A recipe for Warmbier: 1 bottle dark beer, cinnamon, 1/3 cup milk, 1/3 cup sugar, 2 egg yolks. Ginger may also be added to taste. Bring to a boil: beer, cinnamon, milk and sugar (ginger). Stir in the egg yolks and bring back to a boil. Pour through a sieve into heated glasses.

[ii] “Mit feuriger Liebe habe ich die Musik von früher Jugend an mir zu eigen zu machen bestrebt. Sie ist mir eine köstliche Begleiterin und Trösterin durchs Leben geworden; immer unschätzbarer wurde sie mir, je mehr ich ihren unermesslichen Ideenreichthum, ihre unerschöpfliche Fülle würdigen und verstehen lernte; je inniger sich ihre Poesie mit meinem ganzen Sein verwebte.” Georg/IDEEN, p. 6.

[iii] Fischer/HANNOVER, p. 144.

[iv] “Der König war sein eigener General-Intendant. Er entschied über Opern-repertoir und Concertprogramme, über Engagements für erste und zweite Fächer und vertheilte die neuen Opern unter die Capellmeister; nicht selten wurden gewisse Opern, Symphonien und sonstige Concertstücke auf besonderen Befehl angesetzt. Bei Meinungsverschiedenheiten über Charakter und Besetzung von Rollen wurden Correspondenzen nach allen Richtungen hin geführt, ja gelegentlich mit der Wichtigkeit von Staatsgeschäften behandelt, indem dazu die Gesandtschaften im Auslande in Anspruch genommen wurden. Fischer/HANNOVER, p. 146.

[v] “Seine Stellung zur Kunst war eine ideale; er lebte in der Ueberzeugung, dass die Künstler vor Gottes Thron einem besonderen Gerichte unterständen (Ehrlich).” Fischer/HANNOVER, p. 145. [this quoting Ehrlich: see Fischer/OPERN, p. 177]

[vi] “Man hört so oft Äußerungen von Musikliebhabern, welche verrathen, daß selbige den hohen und erhabenen Character der Musik nicht nur nicht erkennen, sondern sogar verkennen; sie betrachten diese nur als ein Mittel zur gewöhnlichen Unterhaltung, wie das Kartenspiel und den Tanz, oder bezeugen ihr vielmehr durch ihre Äußerungen eine nicht viel höhere Achtung als jenem Zeitvertreibe.” Georg/IDEEN, p. 5.

[vii] “… werden nur Wenige recht tief durchdrungen von der Überzeugung, daß nur von Gott allein sie abstamme, diese Himmelsgabe, dieser redende Zeuge der Offenbarung; wird nur Einer bewogen, sie anzuwenden zum würdigen Preise des Allerhöchsten: so ist die Absicht dieser Zeilen erreicht….” Georg/IDEEN, p. 7.

[viii] “Es werden uns durch die Musik Gedanken, Gefühle, Weltbegebenheiten, Naturerscheinungen, Gemälde, Scenen aus dem Leben aller Art, wie durch irgend eine Sprache in Worten, deutlich und verständlich ausgedrückt….” Georg/IDEEN, p. 8.

[xi] Scholz/WEISEN, p. 146.