The Times, London, Issue 18621 (May 28, 1844), p. 4.

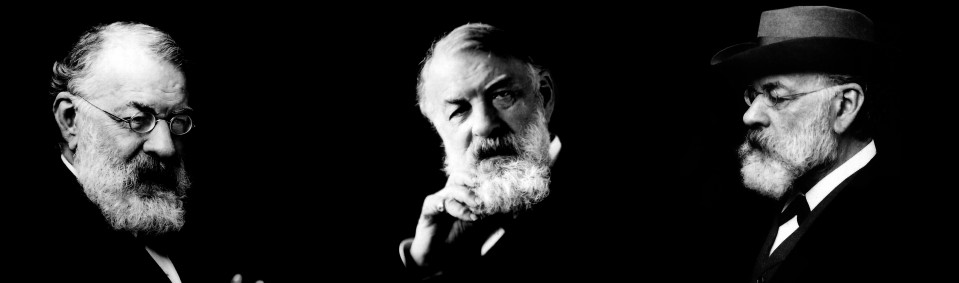

Joseph Joachim acknowledging the audience, drawing thought to be by Mendelssohn, ca. May 1844 (?), with autograph texts by Julius Benedict and Felix Mendelssohn.

Joseph Joachim acknowledging the audience, drawing thought to be by Mendelssohn, ca. May 1844 (?), with autograph texts by Julius Benedict and Felix Mendelssohn.

Brahms-Institut an der Musikhochschule Lübeck, D-LÜbi, ABH 6.3.97

Illustration in Valerie Woodring Goertzen and Robert Whitehouse Eshbach, The Creative Worlds of Joseph Joachim, Woodbridge: Boydell (2021), 28.

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

___________

The fifth concert took place last night, and the following was the programme:—

Sinfonia in B Flat (No. 4)—Beethoven.

Duet, “Stung by horror,” Miss Rainforth and Herr Staudigl (Pascal Bruno)—J. L. Hatton.

Concerto, violin, Herr Joachim—Beethoven.

Overture (Faust)—Spohr.

Duetto, “Pazzerello, O qual ardir,” Mr. Machin and Herr Staudigl (Faust)—Spohr.

Quintetto e Coro, “Ah! goda lor felicitatie,” the principal parts by Miss Rainforth, Miss A. Williams, Mr. Manvers, Mr. Machin, and Herr Staudigl (Faust)—Spohr.

PART II.

Overture (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)—Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

Scherzo (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)—Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

Song, with chorus, “You spotted snakes,” Miss Rainforth, and Miss A. Williams (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)—Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

Notturno, march, and finale chorus (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)—Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

Song, with chorus, “Joy, ’tis a glorious thought,” Herr Staudigl (Fidelio)—Beethoven.

Hunting chorus (The Seasons)—Haydn.

Leader, Mr. Loader [sic; recte: (John David) Loder]; conductor, Dr. F. Mendelssohn Bartholdy.

The society may almost be said in this concert to have taken a new position; in the selection of the music and in the style of its execution it was one of the finest public performances we have ever attended. For once the character of the vocal may be said to have approached that of the instrumental music, and hence this perfect ensemble.

Beethoven’s symphony is that one which, next to the Pastorale, may be said to be the most clear and obvious in its beauties. It has always, therefore, commanded public attention during its progress, and under the baton of Mendelssohn, might be said almost to chain down the ears of the audience. The slow movement, the first portion of it, was played with a degree of perfection in which the nicest ear could not discover a fault.

Beethoven’s violin concerto, which belongs to the class of symphonies, so grand and varied in its design, was played by young Joachim in a manner which caused astonishment in the oldest musicians and professors of that instrument, who discover in a boy of only 13 years of age [sic], all the mastery of the art which it has cost most of them the labour of a life to attain, if indeed any of them have reached to the same excellence by which he is in all respects distinguished. This concerto, however attractive and beautiful as an orchestral composition, has been seldom played by professors of the violin, because the passages, though excessively difficult, convey no notion of that difficulty to those who hear it played, and the merit of the performer has no chance of being appreciated by those who have listened through their attendances on concerts to the gorgeous displays of other writers. Joachim has contrived to throw all this aside, and by his clear and distinct articulation, his perfect intonation, and a conception of his subject which denotes almost a mind kindred with that of the composer, has produced a perfect whole, and so blended the solo instrument with the rest of the composition as to present this great masterpiece with the effect which the author intended. The piece is one of those of which Beethoven himself—and no one exercised a severer judgment on his own writings than he did—was proud. But the extraordinary talent of Joachim is but described in part by what has been said of his manner of playing this concerto. He appeared himself as a composer also, having constructed two beautiful cadences, one for the first and the other for the last movement, into which he has infused the spirit of the author; has varied while he adopted his subjects, introducing into them still greater difficulties of execution, yet never deviating from the main design. Many will hardly believe that Joachim could himself have written these cadences, but of the fact there is, we believe, no doubt; no other hand has touched them. The applause bestowed on him was great, but not more so than his deserts; one universal feeling governed the whole audience. He was interrupted by plaudits wherever they could be permitted, sometimes even to the injury of the composition; and at the close they lasted some minutes.

Till last night there has been no performance from Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream in this country, except the overture. The curtain is now raised, and we are made acquainted with some pieces which are blended with Shakespeare’s play as incidents merely, for the Germans have not tortured it into an opera, and which may take rank with any of the compositions of this master. The scherzo is a most original movement, intricate and difficult, and taxing the powers of the orchestra to the utmost; the march, a magnificent piece, simple yet new. Both of these were encored. With respect to the latter and incident occurred, too characteristic of the great care of Mendelssohn in conducting an orchestra to be passed over. The desire of the audience to have the march repeated had been shown in the usual manner, and could not be doubted. At the moment when it was expected to recommence, the conductor suddenly disappeared from his post, and was seen slowly advancing to the top of the orchestra, the audience all the time keeping silence. Some notes had been omitted, which he must set right before he could allow it to begin again. He then resumed his station, raised his baton, and the march was resumed amidst a thunder of applause. In the finale he returns to that subject which closes the overture, and interweaves the chorus with it, and nothing of the kind could be more perfect. We must adopt these things on our stage, or allow that the Germans go beyond us in their illustration of our own great bard.

The opera of Pascal Bruno, from which the duet of Miss Rainforth with Staudigl is taken, is the work of a countryman, Mr. J. L. Hatton, who has just returned from Vienna, where the entire piece has been performed with a degree of success which has raised the estimation of English talent in that refined capital. The specimen given proves that the success was well deserved. He has formed himself, in his orchestral combinations, upon Mozart, and commits the fault of overlaying the voice by the fulness of them, but many of his effects are quite his own, and his general talent is undoubted. The duet was very finely sung, both by Miss Rainforth and by Staudigl.

In the selections from Faust also the boundary of the overture was passed to introduce us to the opera itself, and the acquaintance with it was most satisfactory. The overture is one of the finest Spohr has written; the hint of the double orchestra, employed in the minuet which leads from the overture into the opera itself, is taken obviously from Don Giovanni, but he has worked the subject after his own admirable manner.

We ought not to take leave of this concert without noticing the marked improvement in the discipline and general effect of the orchestra in the short time since Mendelssohn has become the conductor and assumed the absolute control over it. Except perhaps in some portion of the vocal music, when the accompaniment was too powerful for the voices, not a fault, not a slip was to be detected. All lovers of music and all professors must acknowledge their great obligation to him; he has solved the great problem of the occasional inefficiency of this orchestra in showing that its component parts were most excellent, and that nothing was wanted but a good conductor who could acquire their confidence, and bring out their inherent powers. He has proved, what has often been asserted, that the same conductor must act uniformly in order to insure the success of a great concert. That there are artists already here, English as well as foreign, who could accomplish this, is not to be denied; but to produce willing obedience a great name is wanted, and that name is Mendelssohn. He was received with the most cordial and vehement applause, not only on his first appearance, but whenever he presented himself in the orchestra.